I

The Partition of Bengal

“…It is a strange idea, a foolish idea… to think that a nation which has once risen, once has been called up by the voice of God to rise, will be stopped by mere physical repression. It has never so happened in the history of a nation, nor will it so happen in the history of India. A storm has swept over us today. I saw it come,[1] I saw the striding of the storm-blast and the rush of the rain, and as I saw it an idea came to me. What is this storm that is so mighty and sweeps with such fury upon us? And I said in my heart, ‘It is God who rides abroad on the wings of the hurricane, it is the might and force of the Lord that manifested itself and his almighty hands that seized and shook the roof so violently over our heads today.’ A storm like this has swept also our national life… Repression is nothing but the hammer of God that is beating us into shape so that we may be moulded into a mighty nation and an instrument for his work in the world. We are iron upon his anvil and the blows are showering upon us not to destroy but to re-create. Without suffering there can be no growth…”

— From Sri Aurobindo’s Speeches, pp. 99-100

Since the Battle of Plassey in 1757, which put its seal upon the fate of India and gave her over to the possession of the British for about two hundred years, nothing had happened in the country, not even the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857, of comparable political significance till the Partition of Bengal on the 16th of October, 1905. The Partition of Bengal was the reawakening and self-affirmation of a very ancient nation. The political tide turned. A long night of serfdom, oppression, cultural emasculation and economic strangulation, seemed to end for ever, and the first roseate glow of a new dawn of national liberation flushed the eastern horizon.

As many Indians, let alone foreigners, are not fully aware of the causes of the Partition of Bengal and the national forces that sprang up in reaction to it, we propose to pause upon it for a while before proceeding to take up the narrative of Sri Aurobindo’s political activities in the post-Partition period of the history of Bengal and India. Besides, the full significance of the manifold political life of Sri Aurobindo cannot be properly grasped until we put it in its true context, and study it against the tossing background of the national resurgence, which the Partition quickened and intensified on a wider scale. Sri Aurobindo hailed the Partition as a blessing in disguise, for he saw in it the hammering blows of benign Providence beating the torpid nation into a new life, a new aspiration, and a new shape. As Henry W. Nevinson puts it in his book, The New Spirit in India: “He (Sri Aurobindo) regarded the Partition of Bengal as the greatest blessing that had ever happened to India. No other measure could have stirred national feeling so deeply or roused it so suddenly from the lethargy of previous years.”

“We in India fell under the influence of the foreigner’s Maya which completely possessed our souls. It was the Maya of the alien rule, the alien civilisation, the powers and capacities of the alien people who happen to rule over us. These were as if so many shackles that put our physical, intellectual and moral life into bondage. We went to school with the aliens, we allowed the aliens to teach us and draw our minds away from all that was great and good in us. We considered ourselves unfit for self-government and political life, we looked to England as our exemplar and took her as our saviour. And all this was Maya, and bondage…. We helped them to destroy what life there was in India. We were under the protection of their police and we know now what protection they have given us. Nay, we ourselves became the instruments of our bondage. We Bengalis entered the services of foreigners. We brought in the foreigners and established their rule. Fallen as we were, we needed others to protect us, to teach us and even to feed us…

“It is only through repression and suffering that this Maya can be dispelled and the bitter fruit of the Partition of Bengal administered by Lord Curzon dispelled the illusion…”[2]

What was the Partition of Bengal?

In the nineteenth century, Bengal was the most populous province in India. In area also it was the largest, comprising, as it did, the whole of Bengal, Bihar, Chhota Nagpur, Orissa, and Assam. Later, it was found that such a huge territory was proving too much of a burden for a Governor to administer. So, in the interest of a more effective and efficient administration, Assam, constituting Sylhet, Cachar, and Goalpara — all the three Bengali-speaking areas — was separated from Bengal. But even after the separation of Assam, Bengal remained the largest, most populous, and important province with Calcutta as the capital of India. Its population was 78 millions. The Bengalis as a race, having received a better and more widely-spread education on Western lines than the people of any other province, occupied most of the high posts under the British Government, and naturally dominated the political as well as the educational and cultural scenes in the country.

After the severance of Assam, a few more attempts were made by the Government to further reduce the size of Bengal, but nothing was definitely decided upon and done till 1905. In 1903, H.H. Risley, Secretary to the Government of India, wrote to the Chief Secretary to the Government of Bengal a letter, known as the Risley Letter, detailing the proposed further reduction of the area and population of Bengal by sundering the Chittagong Division and the districts of Dacca and Mymensingh from the mother province, and annexing them to Assam. Among the reasons advanced by the Government for the proposal, apart from the vastness of the original province, was the backwardness of the Muslims in education and the general standard of their life. It was thought that by separating East Bengal from the West and tacking it on to Assam, a greater attention could be devoted to the interests of the Muslims who formed the majority community there, and their condition bettered. But the very people of East Bengal for whom the change was proposed would have none of it. Sir Henry Cotton wrote in the Manchester Guardian of England on the 5th of April, 1904: “The idea of the severance of the oldest and most populous and wealthy portion of Bengal and the division of its people into two arbitrary sections has given such a shock to the Bengali race, and has roused such a feeling amongst them as was never known before. The idea of being severed from their own brethren, friends and relations and thrown in with a backward province like Assam, which in administrative, linguistic, social and ethnological features widely differs from Bengal, is so intolerable to the people of the affected tracts that public meetings have been held in almost every town and market-place in East Bengal, and the separation scheme has been universally and unanimously condemned.”

The real reasons for the Partition were, however, quite different. They were, first, that the British Government had been for some time feeling more and more uneasy and alarmed at the steady growth of the nationalist spirit in Bengal, and the conversion of the National Congress from a close preserve of the Moderates, who excelled in the innocuous art of petition and prayer and protest, to a resounding forum and platform for the demand of the nation’s birthright of full and unqualified independence. It was, as Lord Ronaldsay says in his Life of Curzon, “a subtle attack upon the growing solidarity of Bengali Nationalism”. John Morley, speaking as Secretary of State for India in the House of Commons in 1906, said: “I am bound to say, nothing was ever worse done in disregard to the feeling and opinion of the majority of the people concerned.” Henry W. Nevinson writes in his The New Spirit in India: “Such was the Partition of Bengal, prompted, as nearly all educated Indians believe, by Lord Curzon’s personal dislike[3] of the Bengali race, as shown also by his Convocation speech of the previous February, in which he brought against the whole people an indictment for mendacity.” Sir Henry Cotton, who had already denounced the proposal of partition when it was in embryo, says in his New India that the partition was “…part and parcel of Lord Curzon’s policy to enfeeble the growing power and destroy the political tendencies of a patriotic spirit.”

Another reason why the Partition was hustled through in despotic defiance of the swelling chorus of protests from the people and the political leaders of India, and even her well-wishers and sympathisers in England, was the sinister motive of dividing the Bengali race by driving a wedge between the Hindus and the Muslims. Sir Bampfylde Fuller, who was appointed the first Lt. Governor of East Bengal and Assam, declared, according to Surendra Nath Banerji, “half in jest and half in seriousness, to the amazement of all sober-minded men that he had two wives, Hindu and Mohammedan, but that the Mohammedan was the favourite wife.” Nevinson confirms Curzon’s flirtations with the Muslims when he says: “Always impatient of criticism, Lord Curzon hastened through East Bengal, lecturing the Hindu leaders and trying to win over the Moslems.”[4] Lord Curzon himself remarked, when he was on a tour of East Bengal, “that his object in partitioning was not only to relieve the Bengali administration, but to create a Mohammedan province, where Islam could be predominant and its followers in ascendency.” We know now how the poisonous seed of Hindu-Moslem disunity was sown in Bengal, and under what benign auspices! History perhaps records no more brazen confession, which is a virtual self-indictment, of one who was sent by Great Britain to preside over the destinies of over three hundred million people of a very ancient and cultured nation.

Soon after the publication of the Risley Letter, to which we have already referred, there arose a mounting volume of indignant protest all over Bengal, and East Bengal which, according to Curzon, was going to be particularly benefited by the scheme of Partition, was perhaps the loudest in its denunciation. “The people of Dacca, Mymensingh and Chittagong organised in course of the following two months (December 1903-January 1904) about 500 protest meetings to voice forth their strong disapproval of the proposed change.”[5] The tempo of the agitation went on rising by leaps and bounds, and the Swadeshi idea filtered even to the most interior and remote parts of Bengal, and through Bengal to Gujarat and other parts of India. In the meantime, the proposal of the partition was undergoing various amendments and alterations, in strict secrecy, at the hands of the august arbiters of India’s destiny, and the public was kept studiously in the dark. The air was tense with forebodings. The thundering protests of the people were falling on stone-deaf ears. It was confidently assumed by the bureaucracy that the protests were motivated by the vested interests of a handful of educated Bengalis and landlords, and would naturally die down if only met with cold indifference. But the autocrats had reckoned without their host. The studied indifference, which was nothing short of callousness, added fuel to the fire — the agitation began to take on dangerous proportions. At last, on September 1, 1905, the India Government Gazette came out with the portentous proclamation, couched in positive terms, and it triggered off a tremendous explosion of national fury. For, the people had been hoping against hope that their impassioned protests would at last touch a chord even in the cynical heart of the Government. But though a despotic monarch may be moved to relent, a despotic bureaucracy is impregnable to human appeal. According to the Proclamation, “the districts of Dacca, Mymensingh, Faridpur, Backergunge, Tippera, Noakhali, Chittagong, the Hill tracts, Rajshahi, Dinajpur, Jalpaiguri, Rangpur, Bogra, Pabna, and Malda which now form the Bengal division of the Presidency of Fort William will, along with the territories at present under the administration of the Chief Commissioner of Assam, form a separate province of Eastern Bengal and Assam.” The new province, it was also declared, would be under a Lt. Governor, and function as a separate unit from the 16th October, 1905.

Thus, at one fell blow, the British Government wanted to kill the “seditious” patriotism of the Bengali race, and disrupt Hindu-Moslem unity. The partition of Bengal became “a settled fact”. It threw down the glove to the nationalist spirit of Bengal. It was not, evidently, a solicitude for efficiency of administration that had prompted the Partition — that could have been as well compassed by the substitution of the Presidency Governorship like that of Bombay and Madras — but, as we have seen, it was the tyrant desire to cow down and crush the agitation for national freedom. And how did Bengal meet the Challenge? The whole province rose in indignant revolt to oppose the Partition, and continued to oppose it so long as it was not abrogated. And abrogated it was, though after a long and bitter struggle. The rebel spirit of freedom compelled the British bureaucracy to yield to its insistent demand and unsettle “the settled fact”!

On the 16th October, 1905, the fated partition came into force. “On that day”, says Nevinson in his book, “…thousands and thousands of Indians rub dust or ashes on their foreheads; at dawn they bathe in silence as at a sacred fast; no meals are eaten; the shops in cities and the village bazaars are shut; women refuse to cook; they lay aside their ornaments; men bind each other’s wrists with a yellow string as a sign that they will never forget the shame; and the whole day is passed in resentment, mourning, and the hunger of humiliation. In Calcutta vast meetings are held, and the errors of the Indian Government are exposed with eloquent patriotism. With each year the indignation of the protest has increased; the crowds have grown bigger, the ceremonial more widely spread, and the fast more rigorous.” Valentine Chirol writes in his The Indian Unrest: “…The Partition was the signal for an agitation such as India had not witnessed… monster demonstrations were organised in Calcutta and in the principal towns of the mofussils.” Abanindra Nath Tagore, the great artist, in his Bengali book, Gharoya, describes, in his picturesque way, the unprecedented upheaval of national feeling in which they all participated under the leadership of his uncle, Rabindranath Tagore. Rabindranath sang out in rousing strains the agony of outraged nationalism. He took an active part in collecting funds for the Swadeshi work, and went about the city, and even entered into the mosques of the Muslims, binding the wrists of his compatriots with the sacred thread, rakhi, in token of brotherly love and unity. Extremists and Moderates, Hindus and Muslims, young men and old, the rich and the poor, married women and young girls, all rose, as if from a long sleep, to greet the dawn of national awakening. A new life flowed, full and fast, through the province, like a torrent of fire. The skies were rent with the cries of Bande Mataram, the inspired and inspiring national hymn. It was, indeed, a glorious awakening, a virile self-assertion of a people branded by Macaulay with the stigma of effeminacy and cowardice. “In a few months’ time,” writes Lala Lajpat Rai in his Young India, “the face and the spirit of Bengal was changed. The press, the pulpit, the platform, the writers of prose and poetry, composers of music and playwrights — all were filled with the spirit of nationalism…. Volunteer corps were organised, and Sabhas and Samities and Akharas leaped into existence by hundreds where Bengali young men began to take lessons in fencing and other games.”

The first casualty in this vigorous onslaught of anti-Partition agitation was the British textile goods. Swadeshi, which Sri Aurobindo had been inculcating from even much before the partition, received a sudden creative impetus. “The movement achieved a great success, and became widely popular with the masses. Foreign cloth shops were picketed, foreign textiles were burnt in huge bonfires in market places and on crossings and roads. The family priests refused to perform marriage ceremonies if either of the couple was clad in cloth other than Swadeshi. Swadeshi pledges were taken at meetings,” writes Dr. S.C. Bartarya in his book, The Indian Nationalist Movement. He says further: “Swadeshi was an economic weapon to achieve India’s industrial advance and economic regeneration. The Boycott[6] with a programme of boycott of British goods, renunciation of titles, resignation from Government services, and withdrawal from Government educational institutions, was a weapon forged to force the Government to stop repression and undo the Partition.” Frightened and flustered, the Englishman, an influential Anglo-Indian paper in Calcutta, wrote: “It is absolutely true that Calcutta ware-houses are full of fabrics that cannot be sold…. Boycott must not be acquiesced in or it will more surely ruin British connection with India than an armed revolution. Lord Ronaldsay writes in his The Heart of Arya-varta: “The Swadeshi movement rushed headlong impetuously like some mighty flood, submerging them, sweeping them off their feet, but revitalising their lives.”

Along with the British goods, foreign salt and sugar were also boycotted. The growth of national industries received an unforeseen stimulus. The Bengalis, who had been for long rather apathetic to commercial and industrial enterprises, suddenly seemed to develop a phenomenal aptitude for them, and achieved signal success in the course of a few years. Mill-made textiles, hand-loom products, medicines, chemicals for various purposes, toilet goods, woollen fabrics, hosiery, shoes etc. began to be manufactured and marketed on an ever-widening scale. The textile mills of Gujarat came forward with remarkable promptness and generosity to help Bengal in respect of textile goods, and it contributed to a substantial increase and expansion of their own business into the bargain. All this was the laudable fruit of Lord Curzon’s malicious policy. Swadeshi, which had really had its birth in the days, and principally by the initiative, of Sri Aurobindo’s maternal grand-father, Rishi Rajnarayan Bose, received an unprecedented fillip by the anti-Partition agitation, and became an abiding feature of the all-round national regeneration.

The second casualty in the anti-Partition campaign was the education imparted on Western lines and calculated to turn out subservient clerks and scribes of the alien Government. The existing system of education was, according to Sri Aurobindo, intrinsically demoralising on account of its “calculated poverty and insufficiency, its antinational character, its subordination to Government and the use made of that subordination for the discouragement of patriotism and the inculcation of loyalty.” Government schools and colleges were boycotted, and new ones started to impart national education free from Government control. The humanities and sciences were intended to be taught in them, keeping in view the building up of the character of the students and instilling in them love of Mother India, a knowledge and appreciation of her immemorial culture, and a devoted consecration to her service. The leading part taken by the students all over Bengal in the boycott and the picketing, and the stirring of patriotic feeling in the hearts of the people fluttered the Government, and the Pedlar and Carlyle Letters, which sought to repress the students’ national activities and gag the singing of the national hymn, Bande Mataram, served, instead, to acerbate the already frayed temper of young Bengal and set ablaze the patriotic fire they strove to quench. The more the repression the greater the upsurge of the spirit of patriotism and dedication. It is blind authoritarianism that seeks to dragoon the rising spirit of a nation into perpetual submission.

The National College of Calcutta, of which Sri Aurobindo became the first Principal in June, 1905, owed its origin to this movement of the boycott of the Government schools and colleges. It was started by the initiative of Satish Chandra Mukherji, the reputed educationist of the time, who had also founded the Dawn Society, and was running the English organ, Dawn, in Calcutta. Almost all the men of light and leading in the city, including Rabindranath Tagore, Hiren Datta, Sir Gooroodas Banerji, Bepin Chandra Pal etc., were among the patrons and supporters of the college, and Benoy Kumar Sarkar and Radha Kumud Mookherji among its young professors. But the new movement for education lacked the basis of an inspired vision, a knowledge of the essential spirit of Indian culture, and the true ideal of national education, and was, besides, still wedded to the current system of Western education in its thought and action. It could not, therefore, produce the high results it promised, and languished and waned in course of time. Though many schools and colleges were established all over Bengal, and, in some of them, a fair measure of success was, indeed, achieved, the education imparted could not be called national — it remained essentially the same Western education with certain important modifications.

The Bengal Partition, as we have tried to show, roused the national spirit as nothing had roused it before, and gave a revolutionary turn to the resurgence of the whole country. What happened in Bengal had its mighty repercussions all over India, notably in Maharashtra, the Punjab, and Madras. The reign of terror, inaugurated in Bengal by the Government, and later extended to the three provinces just mentioned, galvanised the whole nation. The spark of an intense, inextinguishable patriotism, flying from Bengal, kindled a country-wide conflagration. The official report of the Banaras Indian National Congress[7], which was held in December, 1905, records as follows: “Never since the dark days of Lord Lytton’s Viceroyalty had India been so distracted, discontented, despondent; the victim of so many misfortunes, political and other; the target for so much scorn and calumny emanating from the highest quarters — its most moderate demands ridiculed and scouted, its most reasonable prayers greeted with a stiff negative, its noblest aspirations spurned and denounced as pure mischief or solemn nonsense, its most cherished ideals hurled down from their pedestal and trodden underfoot — never had the condition of India been more critical than it was during the second ill-starred administration of Lord Curzon. The Official Secrets Act was passed in the teeth of universal opposition… and the Gagging Act was passed. Education was crippled and mutilated; it was made expensive and it was officialised; and, so, that most effective instrument for the enslavement of our national interest, the Universities Act, was passed.” Gokhale, the very paradigm of moderation, who was by no means unfriendly to the Government, had at last to vent his feelings rather boldly for the sake of truth: “To him (Lord Curzon) India was a country where the Englishman was to monopolise for all time all power, and talk all the while of duty. The Indian’s only business was to be governed, and it was a sacrilege on his part to have any other aspiration…. A cruel wrong has been inflicted on our Bengali brethren, and the whole country has been stirred to its depths in sorrow and resentment, as had never been the case before…. The tremendous upheaval of popular feeling which has taken place in Bengal in consequence of the Partition, will constitute a landmark in the history of our national progress…. Bengal’s heroic stand against the oppression of a harsh and uncontrolled bureaucracy has astonished and gratified all India…. The most astounding fact of the situation is that the public life of the country has received an accession of strength of great importance, and for this all India owes a deep debt of gratitude to Bengal.” Lala Lajpat Rai expressed the same view when he said: “I think the people of Bengal ought to be congratulated on being leaders of that march (for freedom) in the van of progress…. And if the people of India will just learn that lesson from the people of Bengal, I think the struggle is not hopeless.”

All progressive political leaders of India supported the fourfold programme of Boycott and stood solidly by Bengal on her hour of the gravest trial, for, they knew, the trial of Bengal was the travail of India’s political salvation. Perhaps it was something more, which time alone will reveal. Mahatma Gandhi paid a perceptive tribute to the heroic struggle of Bengal in the following words: “The real awakening (of India) took place after the Partition of Bengal…. That day may be considered to be the day of the partition of the British Empire…. The demand for the abrogation of the partition is tantamount to a demand for Home Rule…. As time passes, the nation is being forged…. After the partition the people saw that they must be capable of suffering. This new spirit must be considered to be the chief result of the partition.”

The Partition was, in fact, the focal point and accelerating force of the renaissance in India, which had begun with Ram Mohan Roy as its foremost herald and pioneer. It gave a vision and a direction of the path, and a glimpse of the glorious destiny towards which the nation was marching. An outburst of the creative urge, clearly visible in many spheres of the national life, intellectual, aesthetic, and spiritual, found now a unifying focus of self-expression. And when Sri Aurobindo identified nationalism with Sanatana Dharma — “I say that it is the Sanatana Dharma which for us is nationalism” — he recovered at one bound the highest values and widest ideals of the nation, leavened patriotism with spiritual realism, and swept it out of its narrow orbit into the vastness of a universal consummation. Nationalism became in his hands a liberating universalism, and the freedom of India a promise and precondition of the eventual freedom of the soul and body of the commonwealth of humanity. But, as a prophet and precursor, Sri Aurobindo was much in advance of his time. The spirituality which he infused into politics was, for a time, overlaid by inferior or extraneous elements, the dawn-blush covered up by the pall of an invading mist. Ethics then stepped in to do the necessary work of salvaging and sublimation, to give Indian politics a higher push, a purer content. But ethics is half-blind. However firm in faith and strong in self-sacrifice, it is arbitrary in its inhibitions and impositions, crude and cavalier in its repressions, rigid and exclusive in its insistences, and incapable of dealing with a wise and victorious flexibility with the complex forces of life. But the hour of its political domination has almost passed, and its cleansing but cramping spell is dissolving under the shocks of harsh realities, leaving the field clear for the influx of a dynamic, militant, conquering spirituality, the twin-force of Brahminhood and Kshatriyahood,[8] to lead India and the world towards the integral self-fulfilment of Nara-Narayana, the Divine Being in man.

We shall now follow the subsequent political movement in the country, and study what constituted Sri Aurobindo’s contribution to it.

II

“We do not affect to believe, therefore, that we can discover any solution of these great problems or any sure line of policy by which the tangled issues of so immense a movement can be kept free from the possibility of inextricable anarchy in the near future. Anarchy will come. This peaceful and inert nation is going to be rudely awakened from a century of passivity and flung into a world-shaking turmoil out of which it will come transformed, strengthened and purified.[9] There is a chaos which is the result of inertia and the prelude of death, and this was the state of India during the last century. The British peace of the last fifty years was like the quiet green grass and flowers covering the corruption of a sepulchre. There is another chaos which is the violent reassertion of life, and it is this chaos into which India is being hurried today. We cannot repine at the change, but are rather ready to welcome the pangs which help the storm which purifies, the destruction which renovates.

“One thing only we are sure of, and one thing we wear as a life-belt which will buoy us up on the waves of the chaos that is coming on the land. This is the fixed and unalterable faith in an over-ruling Purpose which is raising India once more from the dead, the fixed and unalterable intention to fight for the renovation of her ancient life and glory.[10] Swaraj is the life-belt. Swaraj the pilot, Swaraj the star of guidance. If a great social revolution is necessary, it is because the ideal of Swaraj cannot be accomplished by a nation bound to forms which are no longer expressive of the ancient immutable Self of India. She must change the rags of the past so that her beauty may be readomed. She must alter her bodily appearance so that her soul may be newly expressed. We need not fear that any change will turn her into a secondhand Europe. Her individuality is too mighty for such a degradation, her soul too calm and self-sufficient for such a surrender… She will create her own conditions, find out the secret of order which Socialism in vain struggles to find, and teach the peoples of the earth once more how to harmonise the world and the spirit.[11]

“If we realise this truth, if we perceive in all that is happening a great and momentous transformation necessary not only for us but for the whole world, we shall fling ourselves without fear or misgivings into the times which are upon us. India is the Guru of the nations, the physician of the human soul in its profounder maladies; she is destined once more to new-mould the life of the world and restore the peace of the human spirit. But Swaraj is the necessary condition of her work, and before she can do the work, she must fulfil the condition.”[12]

The above extract mirrors the vision, the faith, the hope, and the courage with which Sri Aurobindo flung himself into the turmoil of the Indian political movement in 1906. He did not take the plunge, impelled only by an intense patriotic ardour. His spiritual vision had foreseen the drift and significance of the many-sided renaissance[13] that was taking place in India, and of which the revolution in Bengal was but a political prelude. That was why he did not fear the chaos that appeared to be imminent. For, he knew that it was not the chaos of inertia, which leads to disintegration, but the chaos of the resurgent forces of regeneration, the transitional chaos of the aggressive self-assertion of a rejuvenated national life. He welcomed, and helped with full knowledge, the revolution that was sweeping down upon the country, to chum a new dawn out of the heaving gloom of the moment. He saw with his Yogic vision God’s purpose writ large upon the foaming waves of the national revolution,[14] and collaborated with it in its realisation. Unswayed by the ignorant human notions of good and evil, undismayed by the hurtling forces of destruction and confusion, undeterred by the misunderstandings of his colleagues and followers, firm in his steps and careless of fate and consequence, he followed the inner Gleam wherever it led him, with the utter self-abandon of a child. It was the self-abandon whose mighty potentialities Sri Ramakrishna had realised and illustrated so marvellously in his epoch-making life. Sri Aurobindo visualised the destiny of India, of which he speaks in the above extract, and became an instrument in God’s hand for its moulding, at first, through politics, and later, through spirituality. He fought for the political freedom of India, but only as a step and means to the realisation of the spiritual mission of her soul — the regeneration of humanity, and its evolutionary ascent from the mind to the Supermind. His vision was never confined to the political and economic, the cultural and moral freedom and greatness of his motherland; it embraced the whole world. Seen in this perspective, his whole life appears to be of one piece, a gradual, though at times sudden, unfolding of a single aim and purpose — the steady pursuit and accomplishment of a single mission.

The official History of the Congress by Pattabhi Sitaramayya gives in figurative language a true estimate of Sri Aurobindo’s political life in Bengal from 1906 to 1909. But it does not — because it could not — give any idea of the wider and deeper implications even of his political work, which was fraught with incalculable possibilities for the world.

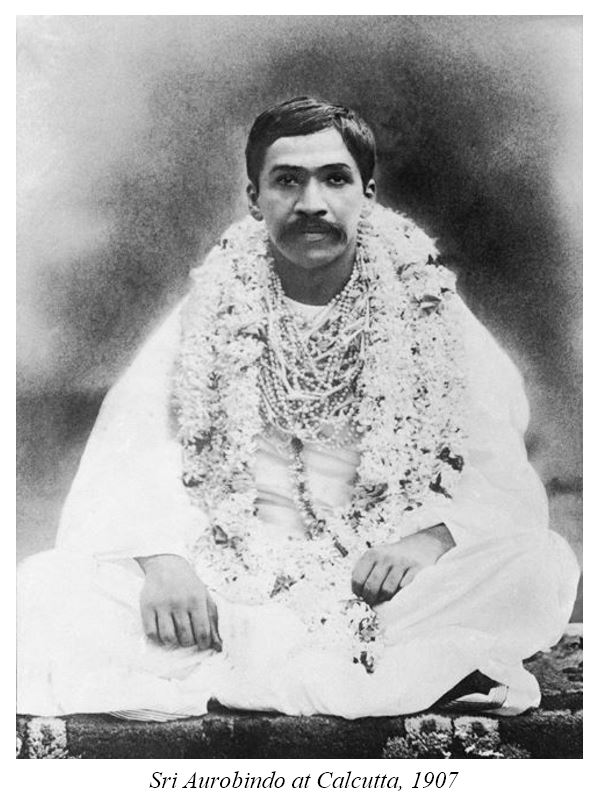

“Aurobindo shone for years as the brightest star on the Indian firmament. His association with the National Education movement at its inception lent dignity and charm to the cause…. Aurobindo’s genius shot up like a meteor. He was on the high skies only for a time. He flooded the land from Cape to Mount with the effulgence of his light.”

We have based our study of the political life of this “brightest star on the Indian firmament” on the fact, borne out by the unbroken tenor of his whole life and the essential unity of his vision, thought and action, that his politics was the politics of a Yogi, and not that of a mere politician. And we shall continue our study on the same line, in the confident hope, amply supported by the verdict of contemporary leaders, whom we shall presently quote, and sufficient circumstantial evidence, that it alone can lead us to a correct explanation of what has remained an unsolved riddle to the world, so far as Sri Aurobindo’s political life is concerned. A polychrome personality, preaching at once passive resistance and armed insurrection, giving different counsels to different colleagues and followers, and equally encouraging even contradictory aims and inclinations in them, but infallibly inspiring them all with a fervent love of Mother India, and a passionate zeal for self-sacrifice in the cause of her freedom — such a calm, complex and masterful personality can be only that of a Yogi. It cannot be assumed or feigned. If it is a mystery and a paradox, or even a farrago of glaring inconsistencies to our rational mind, it is an undeniable truth and fact of spiritual experience. Vivekananda, if he had been alive at the time, would have easily appreciated it. The intuitive insight of Rabindranath Tagore, Brahmabandhab Upadhyaya, and Sister Nivedita clearly perceived it.

Human nature is too complex and diverse, the path of its evolution too mazy and meandering, and the world-forces too tangled and conflicting to permit of a single rigid line of thought and action to lead to any enduring result. Our mind sees only one clear-cut way, and pursues it between its blinkers with a dogmatic faith. But the Yogi commands a total view of the flowing continuum, and has the plasticity to vary his thought and action with the varying trends of its complex operation. He moves in tune with the universal movement even when he concentrates on a limited objective, because he sees with the eye of the Infinite. Not mind-made laws, but the Will of the overruling Providence directs his steps. If he appears to act as an agent of destruction, like Parashurama, or Sri Krishna in Kurukshetra, it is only to clear the path to a renewal and reconstruction. If he appears to blink at bloodshed, it is only in the interest of the creation of a nobler strain of it, and for laying the foundations of a more free and fruitful peace. His apparent inconsistencies spring from his superhuman capacity for acting variously in varying circumstances, and meeting every contingency with the serenity of an inexhaustible resourcefulness. He acts not for transient success and flattering results, but for the fulfilment of the Divine Purpose, in which alone lies the ultimate harmony and happiness of the human race.

We have already quoted extensively from Bepin Chandra Pal who speaks of Sri Aurobindo as the “master”, and as “marked out by Providence to play in the future of this (national) movement a part not given to any of his colleagues and contemporaries”; and of his nationalism as “the supreme passion of his soul”. He further says, “Few, indeed, have grasped the full force and meaning of the Nationalist ideal as Aravinda has done…. By the verdict of his countrymen, Aravinda stands today among these favoured sons of God….” Tilak, as we have seen, paid a glowing tribute to him when he said that there was “none equal to Aravinda in self-sacrifice, knowledge and sincerity” and that “he writes from divine inspiration”. Lajpat Rai speaks of Sri Aurobindo as a nationalist leader in the following words: “…a quiet unostentatious, young Hindu, who was till then obscure, holding his soul in patience and waiting for opportunities to send currents of the greatest strength into the nation’s system. He was gathering energy….” All these are, indeed, remarkably perceptive appreciations of the nature of Sri Aurobindo’s political leadership. But the highest appreciation and warmest homage came from the immortal poet Rabindranath Tagore, who later achieved world renown as a Nobel-Laureate, and from Brahmabandhab Upadhyaya, the fiery champion of Hinduism and militant Nationalism in Bengal, who had made a profound impression on Rabindranath and Bepin Pal, and helped the former in organising his Shantiniketan as an eductional institution, modelled on the ideals of ancient India. Rabindranath, who was much older, and more experienced in literary and political matters — in fact, all those mentioned above were older than Sri Aurobindo — wrote a poem on Sri Aurobindo hailing him as the “voice incarnate of India’s soul”:

“Rabindranath, О Aurobindo, bows to thee!

О friend, my country’s friend, О voice incarnate, free,

Of India’s soul! No soft renown doth crown thy lot,

Nor pelf or careless comfort is for thee; thou’st sought

No petty bounty, petty dole;…

In watchfulness thy soul

Hast thou ever held for boundless full perfection’s birth

For which, all night and day, the god in man on earth

Doth strive and strain austerely…

The fiery messenger that with the lamp of God

Hath come — where is the king who can with chain or rod

Chastise him?…

Moved by the soul-stirring articles of Sri Aurobindo in the pages of the Bande Mataram and discerning in them the spiritual genius of the writer, Brahmabandhab wrote: “Have you ever seen Aurobindo, the lotus of immaculate whiteness — the hundred-petalled lotus in full bloom in India’s Manasarovar?… Our Aurobindo is unique in the world. In him shines the divine glory of Sattwa in snow-white purity. Vast and great is he — vast in the amplitude of his heart, and great in the magnanimity of his Swadharma as a Hindu. You will not find his peer in the three worlds — such a whole and genuine man, fire-charged like the thunder, and yet as graceful and soft as a lotus-leaf, rich in knowledge, and poised in meditation.[15] In order to free his motherland of the chains of slavery, he has ripped away the meshes of the Maya of Western civilisation, renounced the desires and pleasures of this world, and as a true son of Mother India, devoted himself to editing the paper, Bande Mataram.”

A strikingly sensitive evaluation of Sri Aurobindo’s political work comes from an ex-professor of philosophy at the Baroda College, M.A. Buch, M.A., Ph.D., who writes in one of his books, Rise and Growth of Indian Militant Nationalism:

“The most typical representative of Bengal Nationalism, in its most intense metaphysical and religious form, was Aravindo Ghosh. Nationalism with him is not a political or economic cry; it is the innermost hunger of his whole soul for the rebirth in him and through men like him, in the whole of India, of the ancient culture of Hindusthan in its pristine purity and nobility. He was an intellectual thinker of the highest type, and an accomplished and versatile scholar; but his profound scholarship and his keen and penetrating logic were subordinated to the master passion of his soul, the mystic yearning to realise himself in his God, in his country….

“The extraordinary fervour — the zeal of a new nationalism — came upon Aravindo Ghosh like a divine frenzy…. This nationalism is not a trick of the intellect; it is an attitude of the heart, of the soul; it springs from the deepest part of our nature which intellect can never fathom…. The nationalism of Aravinda Ghosh was a burning religious emotion, the voice of God in man, the invincible demand on the part of the great Indian spiritual culture for expression through the reawakened soul to the world. The full meaning and force of this cry can never be perfectly intelligible, translatable into the language of common sense…. It is the unutterable shriek of the political mystic, it is the call of the Beloved; it has simply to be obeyed.[16] The supreme regeneration which India demands can only come from this supreme call of the Motherland — so deep, so religious, so passionate that it carries all before it….”

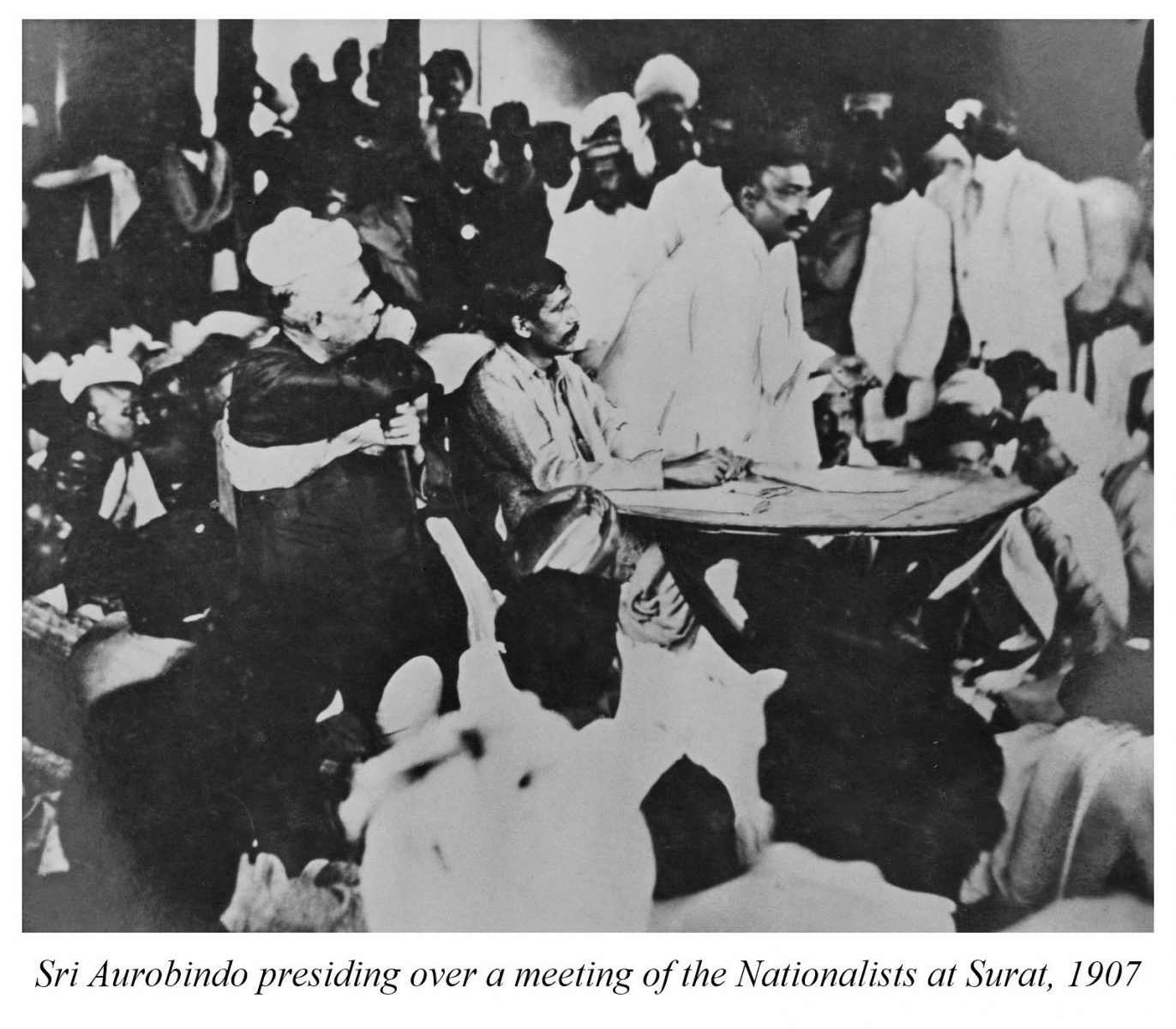

Sri Aurobindo’s spiritual genius and the mystical character of his patriotism are thus admitted on all hands. Almost all the great leaders of the time perceived something of the glowing spiritual fire and dynamis of his personality, and hailed him with one voice as “the brightest star on the political firmament of India”, and the “voice incarnate, free, of India’s soul.” All felt in his presence, and recognised in his writings and utterances, the mystic spell of the born prophet of the spiritual rebirth of India. His soul’s love for all men, equally embracing the high and the low, the virtuous and the sinner; his magnetic attraction; his habitual silence pulsing with his accumulating Yogic power, and infusing it into the soul of the nation; his tranquil vision scanning the distant horizons[17]; and his absolute surrender to the Divine Light that directed his steps[18], marked him out, even in those days of hectic agitation and menacing anarchy, as one destined to leave an indelible stamp upon the history of mankind. Youngest in age among the leaders, he was honoured and respected even by the oldest in wisdom. Shy of publicity, he was thrust upon the presidential chair even where political giants like Tilak, Bepin Pal, and Lajpat Rai strode the rostrum. His humility and self-effacement served as a crystalline channel for the Light and Force of the Divine to stream upon his travailing country.

III

“…There are times when a single personality gathers up the temperament of an epoch or a movement and by simply existing ensures its fulfilment…. Without the man the moment is a lost opportunity; without the moment the man is a force inoperative. The meeting of the two changes the destinies of nations and the poise of the world is altered by what seems to the superficial an accident. Every great flood of action needs a human soul for its centre, an embodied point of the Universal Personality from which to surge out upon others[19]…. History lays much stress on events, a little on speech, but has never realised the importance of souls…. Only the eye of the seer can pick them out from the mass and trace to their source these immense vibrations….”

— “Historical Impressions” by Sri Aurobindo

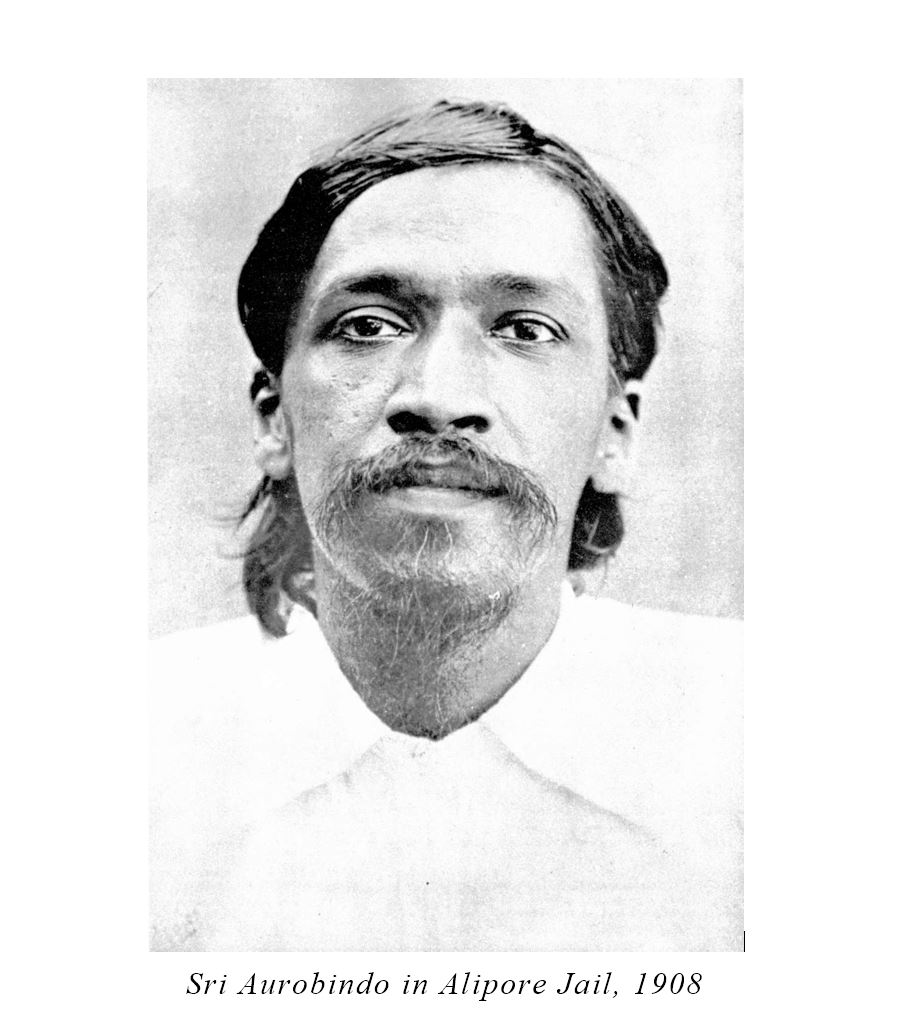

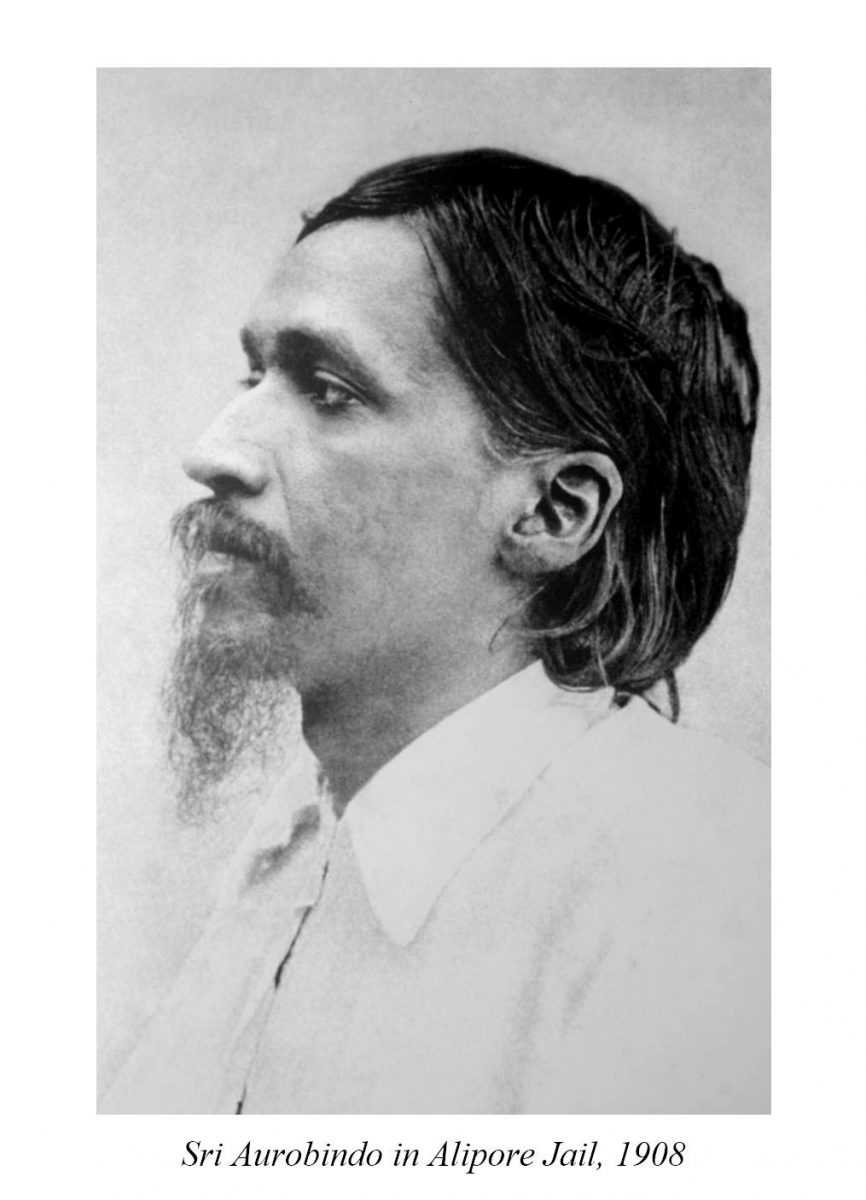

The four outstanding spiritual experiences which had come to Sri Aurobindo as prophetic gifts of God, his subsequent practice of Yoga and its guidance by the Divine Light, which gradually took charge of his whole being and moved it, as we learn from his confidential letters to his wife, brought to light by the police during his trial in the famous Alipore Case, and the spontaneous, perceptive homage of some of his greatest contemporaries, whom we have already quoted, — all these go to prove that here was one who was born to a historic mission, and who knew, more or less clearly, what he had been sent to attempt and accomplish. Our first point that Sri Aurobindo’s politics was the politics of a Yogi, divinely directed and multiply oriented, preluding and preparing the rebirth of the soul of India for the regeneration of mankind, has thus been substantially confirmed.

This leads us to another point, a collateral issue, which we have to tackle here, if we would understand the whole meaning and significance of the renaissance in India, of which Ram Mohan Roy was the first herald and initiating genius.[20] Every great revolution, spiritual, social, political, or scientific, is a release of the mighty ideative and dynamic forces of the Time-Spirit, which seeks to inaugurate a new order or a new era in a nation, society, or humanity. And the Time-Spirit incarnates itself in one or two individuals who are born to be its precursors or prophets, priests and realises. Both the forces, ideative and dynamic, of a revolution work at once in a sort of polar interaction between concentration and diffusion. There is a concentration of them in the pioneers and realisers, who are used as epitomes and vessels, sending forth the electric currents of creative inspiration[21], and a dilution and diffusion in the commonalty for the preparation of the field of their action in the appointed hour. This is the double aspect of every revolution, viewed from the stand-point of its birth, growth, and expansion; and history amply illustrates this truth. What is conscious and articulate in the prophets and torch-bearers, remains, in the beginning, subconscious in the people[22], and throws out stray sparks of its urge and intention in the minds of the elite. Mostly it is felt as an inchoate but persistent aspiration, a vague and indefinite yearning, an instinctive reaching out towards a delivering change. Some of the elite receive its thought-waves, and express them as best they can, each in his own way. But there is, more often than not, a distortion or diminution of them in the minds of the elite who cannot help mixing them with their own prejudices and preconceptions. It is only the prophets who embody and express the inspirations of the Time-Spirit in their purity, so long as they remain loyal to it in the depths of their being. Pythagoras and Plato, Zoroaster and Christ and Mohammed, Leonardo, Galileo and Newton, Mirabeau, Danton, Robespierre and Napoleon, Mazzini and Garibaldi, Marx and Lenin etc., in the West, and Rama, Sri Krishna, Mahavira and Buddha, Shankaracharya and Chaitanya, Sri Ramakrishna and Swami Vivekananda etc., in India, all have been, in their different spheres of work, such prophets and pioneers, or executors and realisers of the invincible Will of the Time-Spirit.

The working of the Will of the Time-Spirit progresses through a constant tug and tension between the forces of new creation and the forces of conservation, and both are indispensable for the shaping of the future. The forces of conservation make for continuity with the past and the transmission of all that was essential, live, and productive in it into the mould of the present, and it is out of the pregnant present, however desolate and chaotic it may appear on the surface, that the new forces surge out to construct the future. But the whole movement is a very complex process, baffling to the rational mind of man. The prophet or pioneer is one who incarnates both the forces of conservation and the forces of new creation. He is the child of the past and the parent of the future[23]. It is not always that he brings something brand-new to the nation or the country he represents. Nor is it at all necessary that he should be original in the idea or ideal he holds up for realisation. Buddha was fundamentally indebted to the Upanishads, Christ to Moses and the Old Testament, and Luther to Wycliff and Erasmus. There can be no creation in a void. No genius is a mushroom, or a freak of Nature. No culture that is rootless can revive after it has had its natural decay and death. What is distinctive in the mission of a prophet or a forerunner is a summing up in himself of both the fertile forces of conservation and those of new creation in a harmonious blend, and marshalled in a dynamic, revolutionary drive, powerful enough to cleave through the barrage of opposing forces, towards the building of the future. He has a vision which none else in the epoch possesses in equal measure, an intuitive perception of the course he has to follow, or at least gleams and flashes which lead him through it, and an uncanny suppleness, which often appears as an incomprehensible, unpredictable eccentricity, in his dealings with the interlocked complex of forces, contending for mastery.

So long as he remains loyal to the vision and intuition guiding him from within, he is invincible. He radiates a power which acts with the victorious might of the elemental forces of Nature. “A messenger he”, says Carlyle, “sent from the Infinite Unknown with tidings to us. Direct from the Inner Fact of things; — he lives, and has to live, in daily communion with that…. Really his utterances, are they not a kind of revelation?… It is from the heart of the world that he comes; he is a portion of the primal reality of things…. The ‘inspiration of the Almighty giveth him understanding’: we must listen before all to him.” He, “with his free force, direct out of God’s own hand, is the lightning…. All blazes round him now, when he has once struck on it, into fire like his own. In all epochs of the world’s history, we shall find the Great Man to have been the indispensable saviour of his epoch; — the lightning, without which the fuel never would have burnt.”[24] He may be hooted or persecuted, crucified or poisoned, but his mission can never fail to prosper, for it bears within it the breath and fiat of the Time-Spirit. There may be resistance, more or less vehement and persistent, of blind orthodoxy or entrenched convention; but nothing can stand for long in the way of his work. His creative ideas permeate the people, and evoke a response in them. His touch revives and kindles. He fashions heroes out of common clay. What was at first subconscious in the masses emerges, little by little, into the light of consciousness; what seemed fantastic or chimerical assumes the solidity and definiteness of reality; what was repellent begins to attract. The prophet is then hailed as a deliverer, and canonised.

But if, in a crucial moment of his work, when the tenacity of his faith and the stubbornness of his faithfulness to his vision and intuition would have sustained him, and sped him on, the pioneer falls back on his reasoning mind and suffers its inveterate doubts to cloud his consciousness, or allows himself to be led, not by the inner urge but by the amorphous opinions of the people he is leading, and lets his egoistic ambition get the better of his loyalty to the inner Light, he falls, as Luther fell, or is flung aside, as Napoleon was flung aside. The secret of his success lies in his absolute fidelity to the Light within him, even when it seems obscured for a moment by the swirling dust of Time’s passage. In short, the central psychological factor in a revolution worth the name is the complex and comprehensive personality[25] of the pioneer geared to the Time-Spirit, and receptive and plastic to its inspirations. He is not so much an individual man, experimenting with Truth in the dim light of his faith and reason, and groping his way forward, but a focal point of universal forces, releasing into expression the elements that go to construct the future.

For an objective study of the origin and development of a revolution, it is, therefore, essential to discover the prophetic vision and pioneering inspiration which initiate it. It is in them that we can discern the entire seed and potentiality of it. Otherwise, we see only the ripples and waves it casts up on the surface, and ignore the deeper springs from which they emerge. The protagonist of a revolution is a living focus of its possibilities and a prism of its diverse colours. Not to know him in the inner truth of his being is to miss the real import of his mission and the purpose and significance of the revolution. What historian can hope to study fruitfully the Renaissance in the West without arriving at a proper assessment of the role Leonardo da Vinci played in it? or, the scientific revolution of the modern times without a correct estimate of the part played in it by Newton and Einstein?

We have, therefore, set out to study the history of the renaissance (not the freedom movement only) in India by ascertaining, on the solid basis of historical data and contemporary evidence, as to who was the personality that can be called the prophet and pioneer of it.

The renaissance can, of course, be traced back to Raja Ram Mohan Roy, as we have already said above. Ram Mohan’s contribution to religious, social and political reconstruction of India was immense and magnificent. Dayananda Saraswati sought to give a new orientation to the religious and social life of the nation by linking it to its ancient roots. But not until Sri Ramakrishna and Swami Vivekananda brought down a tidal wave of creative spirituality and touched every aspect of Indian life into an unwonted glow of galvanised consciousness, did the lineaments of the renaissance shine out on the horizon with a radiant distinctness. We cannot measure the debt we owe to the lightning personality of Vivekananda. Sri Aurobindo says about him: “We perceive his influence still working gigantically, we know not well how, we know not well where, in something that is not yet formed, something leonine, grand, intuitive, upheaving that has entered the soul of India, and we say: ‘Behold, Vivekananda still lives in the soul of his Mother and in the souls of her children.’” The first incipient outline of an unprecedented synthesis was thus traced, and the perennial founts of India’s mighty spirituality were unsealed. Bankim, Rabindranath Tagore, Abanindranath Tagore, Jagadish Chandra Bose, and a few others evoked various powers of the soul of India and considerably helped the expansion and enrichment of her culture. In the field of politics and social reform, there came a glorious band of dynamic personalities, all impelled by the overmastering urge to serve the motherland and raise the nation to the manifold greatness of its destiny. And yet, when we scrutinise the aims and achievements of all these illustrious personalities, we are driven to conclude that there was not one among them who had a global vision of all the potentialities, spiritual, moral, intellectual, aesthetic, cultural, political and economic, of the renaissance that was taking place in India. Each of them had his gaze fixed upon one or a few aspects and potentialities, and considered their realisation as the sole object of their endeavour, and perhaps the whole purpose of the national resurgence. That the resurgence meant the re-emergence of the immortal soul of India and its mission for the regeneration and reconstruction of humanity[26], escaped even the most perceptive of them. India waited for her chosen son, the “voice incarnate” of her soul, to touch her into the spring-tide splendour of her renewed life, and the world waited for India’s Light to lead her out of the gloom of its moral and cultural collapse. God beckoned man to rise beyond his animal humanity.

As the individual has his soul, his deathless being, which seeks self-fulfilment in life, so the nation has a soul, its inmost being, which seeks to realise its destiny, “…the primal law and purpose of a society, community or nation is to seek its own self-fulfilment; it strives rightly to find itself, to become aware within itself of the law and power of its own being and to fulfil it as perfectly as possible, to realise all its potentialities[27], to live its own self-revealing life…. The nation or society, like the individual, has a body, an organic life, a moral and aesthetic temperament, a developing mind, and a soul behind all these signs and powers for the sake of which they exist. One may see even that, like the individual, it essentially is a soul rather than has one; it is a group-soul that, once having attained to a separate distinctness, must become more and more self-conscious and find itself more and more fully as it develops its corporate action and mentality and its organic self-expressive life.”[28]

The leader who identifies himself with this nation-soul and feels in himself, not only all its many-branching powers and potentialities, but its urge and inspiration to realise them, is the true pioneer, commissioned to lead the nation to its ultimate destiny. “Nationalism is itself no creation of individuals and can have no respect for persons. It is a force which God has created, and from Him it has received only one command, to advance and advance and ever advance until He bids it stop, because its appointed mission is done. It advances, inexorably, blindly, unknowing how it advances, in obedience to a Power which it cannot gainsay, and everything which stands in its way, man or institution, will be swept away or ground into powder beneath its weight. Ancient sanctity, supreme authority, bygone popularity, nothing, nothing will serve as a plea.

“It is not the fault of the avalanche if it sweeps away human life by its irresistible and unwilled advance; nor can it be imputed as moral obliquity to the thunderbolt that the oak of a thousand years stood precisely where its burning hand was laid. Not only the old leaders but any of the new men whom the tide has tossed up for a moment on the crest of its surges, must pay the penalty of imagining that he can control the ocean and impose on it his personal likes and desires. These are times of revolution when tomorrow casts aside the fame, popularity and pomp of today. The man whose carriage is today dragged through great cities by shouting thousands amid cries of ‘Bande Mataram’ and showers of garlands, will tomorrow be disregarded, perhaps hissed and forbidden to speak. So it has always been and none can prevent it…. Men who are now acclaimed as Extremists, leaders of the forward movement, preachers of Nationalism and embodiments of the popular feeling will tomorrow find themselves left behind, cast aside, a living monument of the vanity of personal ambition…. Only the self-abnegation that effaces the idea of self altogether and follows the course of the revolution with a child-like belief that God is the leader and what He does is for the best, will be able to continue working for the country.[29] Such men are not led by personal ambition and cannot, therefore, be deterred from following the Will of God by personal loss of any kind.

“Revolutions are incalculable in their goings and absolutely uncontrollable. The sea flows and who shall tell it how it is to flow? The wind blows and what human wisdom can regulate its motions? The Will of Divine Wisdom is the sole law of revolutions and we have no right to consider ourselves as anything but mere agents chosen by that Wisdom.[30] When our work is done, we should realise it and feel glad that we have been permitted to do so much. Is it not enough reward for the greatest services that we can do, if our names are recorded in history among those who helped by their work or their speech, or better, by the mute service of their sufferings to prepare the great and free India that will be? Nay, is it not enough if unnamed and unrecorded except in the Books of God, we go down to the grave with the consciousness that our finger too was laid on the great Car and may have helped, however imperceptibly, to push it forward? This talk of services is a poor thing after all. Do we serve the Mother for a reward or do God’s work for hire? The patriot lives for his country because he must; he dies for her because she demands it. That is all.”[31]

“The Will of the Divine Wisdom is the sole law of revolutions and we have no right to consider ourselves as anything but mere agents chosen by the Wisdom.” — This is exactly the truth which Swami Vivekananda knew and preached, and Sri Aurobindo taught and practised all his long life. It was essentially a Yogic Knowledge and a Yogic way of life.

If we would have a total view, in the true perspective, of all the potentialities of the rebirth of India’s soul and the ultimate fulfilment of the destiny of this ancient nation, the dawns of whose culture were luminous with the glory of God in man, we have to discover who among the greatest leaders of India, embodying in himself the powers and purpose of the renaissance, served the Will of God as enshrined and revealed in the nation-soul[32] from the beginning of his life to the very end of it, without being cast aside by the Time-Spirit before his mission was accomplished? We have to discover, not which of the leaders was the true mouth-piece of the will of the nation-soul only to political and economic freedom, or which of them worked for its moral, religious and spiritual greatness, but which of them was the prophet and realiser of its integral fulfilment. Who had the unified vision of all the facets of the national renovation, and the creative will to carve out the many-splendoured future of India? Who among them saw and knew, like Sri Ramakrishna and Swami Vivekananda before him, and proclaimed by the power of his words and the complex pattern of his ceaseless activities, that India was rising, not for herself but for the world,[33] that the world would sink into a perpetual night of cultural darkness unless the light of the soul of India shone out once again to deliver it, and that the political freedom of India, which was the sole aim of the earnest endeavours of most of the leaders, was only an indispensable prelude to the integral freedom, perfection and fulfilment of humanity? Who, among them, remaining absolutely faithful to the directing Light of God, followed the ascending curve of the unfoldment of the nation-soul, phase by phase, stage by stage, flexibly adapting his steps to the rhythms of its progress, in order to lead it to its supreme end?

“God has set apart India as the eternal fountainhead of holy spirituality, and He will never suffer that fountain to run dry. Therefore Swaraj has been revealed to us. By our political freedom we shall once more recover our spiritual freedom. Once more in the land of the saints and sages will burn up the fire of the ancient Yoga and the hearts of her people will be lifted up into the neighbourhood of the Eternal.”[34]

“Once more in the land of the saints and sages will burn up the fire of the ancient Yoga….” Here we have at once a prescience and a prophecy of the colossal work that was to rear its edifice on the secure foundation of political freedom[35]. The integral Yoga was to transform human nature into Divine Nature and human life into Divine Life[36].

IV

“There are some men who are self-evidently super-human, great spirits who are only using the human body. Europe calls them supermen, we call them vibhutis. They are manifestations of Nature, of divine power presided over by a spirit commissioned for the purpose, and that spirit is an emanation from the Almighty, who accepts human strength and weakness but is not bound by them. They are above morality[37] and ordinarily without a conscience, acting according to their own nature. For they are not men developing upwards from the animal to the divine and struggling against their lower natures, but beings already fulfilled and satisfied with themselves. Even the holiest of them have a contempt for the ordinary law and custom and break them easily and without remorse, as Christ did on more than one occasion, drinking wine, breaking the sabbath, consorting with publicans and harlots; as Buddha did when he abandoned his self-accepted duties as a husband, a citizen and a father; as Shankar a did when he broke the holy law and trampled upon custom and ācāra[38] to satisfy his dead mother….”

— “Historical Impressions” by Sri Aurobindo

Let us now pause for a moment upon an important point which crops up at this stage of our inquiry in regard to the prophet and high priest of the renaissance in India: Who can command a total vision of the evolutionary march of a nation and its destiny?

The nation, like the individual, has a triple body — the sthūla or gross, the sūkṣma or subtle, and the kāraṇa or causal. As the gross body of the individual is only the outer crust or coating of the inner being, so the physical body of the nation is only its mutable material covering. To see only its material covering or shell, its social and political configuration, and regard that alone as one’s nation is to miss the truth of its inner and inmost existence. The acorn gives no hint of the oak, or the caterpillar of the butterfly. Saul keeps St. Paul cocooned in himself. We have to see — and how can we, unless we develop the inner sight and the intuitive vision? — also its sūkṣma or subtle body, and the kāraṇa or causal. It goes without saying that all of us do not possess this vision. It is only the intuitive vision, by inner identity, of the causal body that can reveal the truth of the soul of a nation and its mission and destiny. A mere ardently patriotic or economic, political or moral approach to its characteristic mores and behaviour patterns can yield nothing but a partial knowledge of its changing material form. Even history, as it is written, is a crippled explorer of its past, and a blind guide to its future.

Who, then, can see the causal body of a nation, and know its mission and destiny? The question can be answered by a counter-question: Who can see the causal body of an individual and know his destiny? It will be readily conceded by those who have even a rudimentary knowledge of the human soul and its spiritual and psychological constitution that it is only a Yogi who can do it, and none other. The Yogi’s power of self-identification with every being and everything in the world enables him to know its essential reality and its evolving forms. Nothing can be hidden from that vision, as Yogis and mystics have testified in all ages and countries.[39] What is visualised in the causal body is the truth of the soul, whether of the individual or of the nation, and is irresistible in its self-expressive dynamic. But it may — and often does — take long to manifest on the physical plane, the length of the time depending on various spiritual and psycho-logical factors beyond the range of human vision, and also on the degree of the resistance of the physical nature itself. And it is this length of time taken for manifestation or materialisation that gives an apparent plausibility to the facile verdict of the sceptic and the materialist that the words of the prophet are but the rosy dreams of a romantic visionary or the airy castles of an exuberant Utopian. A deeper vision, to which the materialist is usually averse, would reveal the truth that what is in the causal or seminal state passes into the subtle or subliminal through a complex play of forces and, in the same way and in its own time, manifests in the material. The material self-projection of the causal Idea is what is known as the physical universe, to which materialism keeps its vision and action stubbornly confined. The inevitability of the materialisation of the causal truth remains beyond doubt, but its prediction in terms of the time of our reckoning is often a precarious affair.

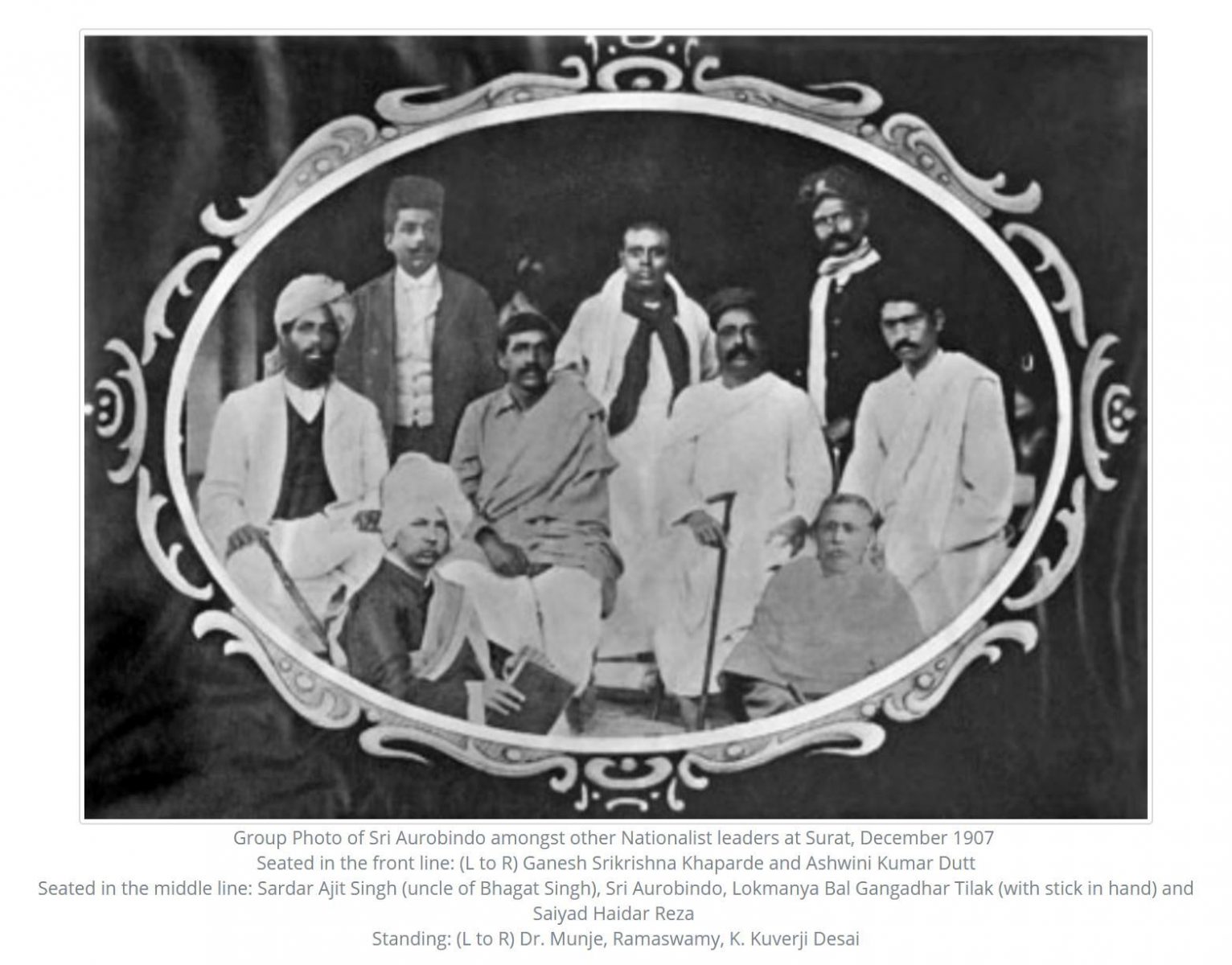

It is an historical fact to which we can no longer turn a blind eye that among the most passionate lovers and devoted servants of Mother India in the modern times, there have been only two who were Yogis, possessing the Yogic vision and intuition — Swami Vivekananda and Sri Aurobindo. Some of the others were disciples of Yogis — Tilak,[40] Bepin Pal, P.C. Mitter of the Anusilan Samity, and Aswini Kumar Datta of Barisal, to name only a few. But, though they were spiritually inclined, they never claimed to possess any intuitive vision or to have attained any such close contact with the Divine as to be able to receive His direct guidance in their active lives. There were many other Yogis, but they do not concern us here, because they were not avowed nationalists.

Love of India was an intense passion of Vivekananda’s being — it was interwoven with his consuming love of God. Nivedita, who lived closer to him and knew him more intimately than anybody else, says that India was the queen of the adoration of the Swami’s heart.[41] But the source of this profound love was more in his spiritual vision than in his blood and upbringing. His spiritual vision penetrated into the prehistoric past of India and made him see her unparalleled glory, her perennial role as the giver of Light to the world, and her massive and varied contribution to the culture of humanity. It made him see, and with equal clarity, and without any biassed slurring over of unpalatable facts, the later decline of her spirituality, its defensive recoil from the commerce of life, which it branded as an illusion and a snare, and its degeneration into a soulless formalism, and the rigidity of a sterile, dogmatic orthodoxy. He was unsparing in his denunciation of the dry-rot from which the culture of the land was suffering, and the inert, unthinking conformism of the mass mind. It made him also see with marvellous lucidity the destiny of India, the final fulfilment of her past promise, and the meridian blaze of the future Light of which the first dawn was witnessed in the age of the Veda. “This is the land from whence, like the tidal waves, spirituality and philosophy have again and again rushed out and deluged the world. And this is the land from whence once more such tides must proceed in order to bring life and vigour into the decaying races of mankind,” declared the Swami. “Before the effulgence of this new awakening in India the glory of all past revivals will pale like stars before the rising sun, and compared with the mighty manifestation of renewed strength, all the many past epochs of renaissance will be mere child’s play.” He was convinced that the mission of India was the regeneration of man and the spiritualisation of the human race.

In almost identical terms, because by an almost identical spiritual vision, has Sri Aurobindo spoken of the glory of India’s past, and the still greater glory of her future. “India of the ages is not dead nor has she spoken her last creative word; she lives and has still something to do for herself and the human peoples… the ancient immemorable Shakti recovering her deepest self, lifting her head higher towards the supreme source of light and strength and turning to discover the complete meaning and a vaster form of her Dharma.”[42] “We do not belong to the past dawns, but to the noons of the future.”[43] “The sun of India’s destiny would rise and fill all India with its light and overflow India and overflow Asia and overflow the world.”[44]

It was this indispensable work, the work of helping the birth of “the noons of the future”; of creating the conditions for the Light of the Spirit to fill all India and “overflow India and overflow Asia and overflow the world”; the work of realising the destiny of India, so that she might fulfil the destiny of mankind; the inevitable evolutionary work of raising man to the sunlit peaks of his being from the dim valleys of his mental consciousness, and unveiling the divine glory in his nature and life, so dear to Vivekananda’s heart, and so glowingly prophesied by him, for which God summoned Sri Aurobindo away from the field of politics to the infinitely vaster fields of supramental conquest. Sri Aurobindo was assured from within of the freedom of India. He knew that the fire he had breathed into the torpid veins of his countrymen, the love and the devotion for Mother India with which he had imbued them, the ardent spirit of service and sacrifice with which he had inspired them, and the programme of non-cooperation and passive resistance which he had chalked out so clearly and forcefully for them to follow, would lead them, in spite of all detours and setbacks, to the cherished goal of independence. As the leading Indian historian, Dr. R.C. Majumdar, says: “While Tilak popularised politics and gave it a force and vitality it had hitherto lacked, Aravinda spiritualised it and became the high-priest of nationalism as a religious creed. He revived the theoretical teachings of Bankim Chandra and Vivekananda, and introduced them in the field of practical politics.[45] Tilak had raised his voice against the policy of mendicancy followed by the Congress, but it was reserved for Aravinda to hit upon a positive approach to the problem. He anticipated Mahatma Gandhi by preaching the cult of passive resistance and non-cooperation as far back as 1906.”[46] “But however much opinions might differ on these points, one must recognise that apart from the general forces working for nationalism, the movement was especially or more directly inspired by the teachings of Bankim Chandra, Vivekananda and Aravinda, who placed the country on the altar of God and asked for suffering and self-immolation as the best offerings for His worship… these teachings… inspired the lives of many a martyr who hailed the scaffold with a smile on their lips or suffered torments worse than death without the least flinching….”[47]

Sister Nivedita, who had read Sri Aurobindo’s fiery articles in the Indu Prakash and heard about him from various sources, saw him for the first time at Baroda, and was immensely impressed by his Yogic bearing, his rock-like calm, his serene poise, vibrating with superhuman power, and the steady gaze of his far-seeing eyes — eyes of “one who gazes at futurity”, as Nevinson has expressed his observation. She promised him unreserved support in his political work, which was then being carried on in secret through Jatin Banerji, Barin, and others in Bengal; for, being in the State service, he was not publicly taking part in the politics. And when Sri Aurobindo left the State service and threw himself into politics, none was so intimate with him, none rendered him so devoted and persistent a help, none appreciated so well the significance of his work as Sister Nivedita, of whom Prof. Atindra Nath Bose says: “His (Vivekananda’s) disciple, Nivedita, took the (revolutionary) fire (from her Master) and blew it among the young nationalists who were seeking a new path.”[48]

A few extracts from Nivedita’s biography, The Dedicated, by Lizelle Reymond, will show the inner affinity and understanding which existed between Sri Aurobindo and the spirited Irish lady, Nivedita, whom Vivekananda had moulded with his own hands and charged with something of his own creative fire:

“…India, ‘Mother India’, had become her Ishta, the supreme object of her devotion, in which she perceived the aim of her life and the peace of her acceptance.

“And in Baroda she made the acquaintance of Aurobindo Ghosh…. He and Nivedita were already known to one another through their writing, as well as through their bond in their love of India[49] and of freedom. To Aurobindo Ghosh, Nivedita was the author of Kali, the Mother. To her, he was the leader of the future,[50] whose fiery articles in the Indu Prakash… had sounded opening guns in the coming struggle, four years before.

“What he (Sri Aurobindo) was doing was to impart an esoteric significance to the nationalist movement, and make it a confession of faith. In appearance a passive type, a quiet — even silent — figure, he was a man of iron will whose work, personality, possessions, earnings, belonged to God and to that India which he considered not as a geographical entity but as the Mother of every Hindu; and he seized hold on the people and created between them and the nation a profoundly mystic bond…. The nationalism he taught was thus a religion in itself, and it was so that he had become the teacher of the nation. He wanted every participant in the movement to feel himself an instrument in the hand of God, renouncing his own will and even his body and accepting this law as an act of obedience and inner submission…. This injunction to act, endure, and suffer without question — to let oneself be guided by the assurance that God gives strength to him who struggles — required sacrifices which became in turn a reservoir of power from which new fighters drew inspiration to go forward. The individual and the community were no longer separated…. Aurobindo Ghosh with his clear insight into the swadharma (law of action) of his own people was suffusing it with a spiritual strength[51] and making it live.

“Aurobindo Ghosh was now out of prison, and Nivedita had her school decorated… to celebrate his release. She found him completely transformed. His piercing eyes seemed to devour the tight-drawn skin-and-bones of his face. He possessed an irresistible power, derived from a spiritual revelation that had come to him in prison…

“With a mere handful of supporters — Nivedita among them — he launched an appeal and tried to rekindle the patriotic spark in the weakening society. His mission was now that of a Yogin sociologist.

“…He was already known as the ‘seer’ Sri Aurobindo, although still involved in political life, and as yet not manifested to his future disciples on the spiritual path. For Nivedita he was the expression of life itself, the life of a new seed grown on the ancient soil of India, the logical and passionate development of all her Guru’s teaching.[52]

“Aurobindo’s open and logical method of presenting his own spiritual experience, and revealing the divine message he had received in his solitary meditation, created the necessary unity between his past life of action and his future spiritual discipline. He said: “When I first approached God, I hardly had a living faith in Him…. Then in the seclusion of the jail I prayed, ‘I do not know what work to do or how to do it. Give me a message.’ Then words came: ‘I have given you a work, and it is to help to uplift this nation…. I am raising up this nation to send forth My word…. It is Shakti that has gone forth and entered into the people. Long since, I have been preparing this uprising and now the time has come, and it is I who will lead it to its fulfilment!’