Biographical Notes

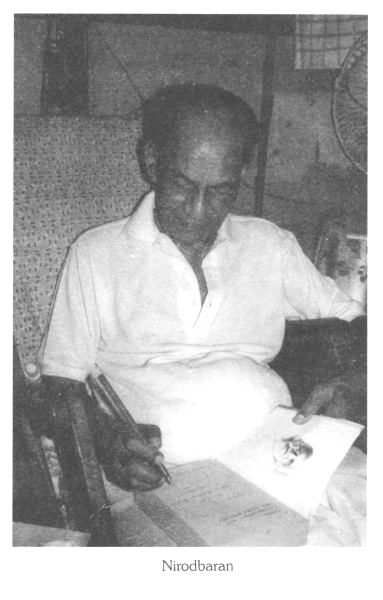

Nirodbaran was born on November 17, 1903 in Chittagong (now in Bangladesh). He lost his father when he was five years old. After passing Matriculation Examination, he participated in the famous Non-Cooperation Movement and was punished with two months’ imprisonment. After passing Intermediate Examination in the first division, he decided to go to England to qualify for the Bar. In 1924, he went abroad, but finally went in for Medical Studies at Edinburgh. After a long six-year course, he took the M.B.C.H.B. Degree and then went on a tour of Europe with his niece. His meeting with Dilip Kumar Roy, the famous musician, in Paris, sealed his fate. His niece, having heard about Sri Aurobindo from Dilip Kumar Roy, met the Mother and was highly impressed. On her repeated requests, Nirodbaran, after coming to India in 1930, met the Mother and was overwhelmed and had a spiritual experience. After some vacillation he finally felt the call and joined Sri Aurobindo Ashram in 1933, leaving behind the prospect of a highly lucrative career. In the Ashram he entered upon a new life and had many experiences and realizations. With Sri Aurobindo’s help and inspiration he flowered into a wonderful poet, (see “Swapnadeep” and “Fifty Poems of Nirodbaran”) His correspondence with Sri Aurobindo is an invaluable treasure. In 1938, when Sri Aurobindo broke his leg, he was drawn into the inner circle of Sri Aurobindo’s personal attendants. He served Sri Aurobindo till his passing away in 1950. He had the extraordinary good fortune of being Sri Aurobindo’s scribe when the latter dictated “Savitri” to him. He had been also engaged with Sri Aurobindo International Centre of Education as a teacher of English, French and Bengali. He has been a prolific writer, in English and Bengali, having to his credit quite a few beautiful books (“Twelve years with Sri Aurobindo” and “Memorable contacts with the Mother” deserve especial mention) and numerous articles which will not only rank as fine literature, but also serve as an invaluable guide for knowing Sri Aurobindo and the Mother, their teachings, their many-splendoured personality and also about the Ashram and the disciples. Nirodbaran is now 98, but he has been carrying on with his usual radiant smile, good humour and incomparable sweetness, candour and humility.

Foreward

My friends have resolved to bring out my old compositions in book form and have requested me to write an introduction to them. It is a matter of regret that I have lost the power which enabled me to write so many books that the readers still remember me. Of course, the power behind my composition was not mine, but of the Guru.

My former capacity by which I am still remembered is lost like the river Falgu and perhaps its current flows in the world and will revive in the next life.

I live in their memory alone.

Nirodbaran

Editorial Preface

Nirodbaran needs no introduction. To his ever-expanding circle of friends he is best known as ‘Nirod-da’, a dear elder brother and warm-hearted friend, ever ready to receive you with his winsome smile and scintillating humour. His long association with Sri Aurobindo and the Mother have invested his life with a magnetic charm, quiet grandeur and simplicity. A simplicity shorn of all pretensions. Age has not withered his mind; he is ever awake, ready to crack jokes and listen to anything interesting, corrects you when you quote wrongly or omit something while narrating some incident connected with the Mother and Sri Aurobindo. His deep intimate knowledge of the Master and the Mother and their disciples have endeared him to all; and to us he brings not only knowledge, but breathes the very atmosphere of his Guru, Sri Aurobindo, though apparently everything seems to be simple.

The idea of the present volume occurred to my mind as I stumbled upon, in the pages of “Mother India”, some old writings of Nirodbaran from time to time. As I read them, I was thrilled by the sheer beauty of his prose, the coruscating wit, the rich allusions, the iridescent poetry and the hidden depth of yearning; vision of a world within world, a sweetness that beckoned; and above all, his overabounding vitality, his sure eye for a significant detail, common sense and intuitive flashes; and a fine distillation in prose of the sweetness and light, of the eternal wonder that is Sri Aurobindo and the Mother. I have been reading his books for long, but in these writings I found something more intimate, more striking, more informative and revealing, and a splendid variety that grips you and lures you on. You have the feeling, while you read these pieces, of gliding along a smooth, flowing stream with its haunting smell and sound.

And not only that. In these writings, one gets a panoramic view, as it were, of the old Ashram-life, the beautiful lives of the disciples, an intimate picture of the unpretentious dedication of their life to the Master and the Mother, their little foibles, the experiences of their salad days, their tireless labour, courage and equanimity in the face of adversity, quiet wisdom, insight from their sadhana, and above all, their love and loyalty to Sri Aurobindo and the Mother. There are serious topics too, like the brilliant pieces on Sister Nivedita. There we get a glimpse of another facet of Nirodbaran’s talent: his analytical power. We have known Nirodbaran, the poet and Nirodbaran, the narrator; but in these pieces on Nivedita, the critic and analyst takes over and brings us rare insights. There are also light, charming pieces, like his description of a picnic where we discover Nirodbaran as one of those eternal children of whom Tagore said in one of his immortal poems: “On the seashore of endless worlds children meet…. They seek not for hidden treasures, they know not how to cast nets.”

These writings — some of them are essays and some were recorded as talks — were published in “Mother India” over a long period of time. We are grateful to Sri Amal Kiran, the Editor of Mother India and also to Sri. R. Y. Deshpande, Associate Editor, for giving us permission to reprint these writings and bring them in a single volume. We also thank Gabriel of Sri Aurobindo Ashram and Miss Manali Chakrabarty, Lecturer in French, St. John’s Church College, Secundrabad and also Mrs. Gopa Basu, Librarian, Sri Aurobindo Bhavan, Calcutta for helping me in ferreting out materials for this volume. Sri Dilip Chatterjee of Sri Aurobindo Pathamandir, Calcutta also deserves our thanks. Sri Aurobindo Bhavan, Barrackpore, decided to publish this volume on the memorable occasion of the bringing of the sacred relics of Sri Aurobindo to the Barrackpore Bhavan in early January, 2001. We are grateful to many other friends, particularly to Dolly, Bani and Jhumur of Sri Aurobindo Ashram; to Dr. Hriday Ranjan Haider, a long-time friend of Nirodbaran and a Senior Trustee of Sri Aurobindo Bhavan, Barrackpore, and also to Sri Dipak Gupta, a never-failing friend to us from the beginning.

These writings keep alive for us the voice of an old friend; these are published at the auspicious moment when Sri Aurobindo comes to Barrackpore in January 2001, the beginning of the new Millenium. May these wonderful pieces deliver us from the pale cast of thought, charge our mind with sparks of the imperishable fire and energy, open up new path-ways and vivify us with our Guru’s parting assurance:

“I shall leave my dreams in their argent air,

For in a raiment of gold and blue.

There shall move on the earth embodied and fair

The living truth of you.”

Sri Aurobindo Comes To Bengal

One cannot think of Bengal without thinking of Sri Aurobindo. India may try to ignore or forget him, the present-day Bengal may be far removed from what Sri Aurobindo’s Bengal was, but he who came and left a white trail blazing across her firmament remains for ever enshrined behind her surface consciousness in spite of the conjoint efforts of various forces to obscure the silver line within. So, as time passes, we find a frequent reference to his name and a re-emergence of his light in the cultural and spiritual life of Bengal, though probably not yet in her political field. True, we hear from all sides tales of woe and cries of lamentation, “Bengal is dead, the Bengal of Sri Ramakrishna, Vivekananda and Sri Aurobindo is moribund.”

Is Bengal really dead? Can a country whose soil has been the Lilabhumi of God with his chosen playmates ever fall into impotence? We must look a little deeper. Though it is no longer that fiery Bengal, neither is it something that has undergone a change beyond recognition. The change is only on the surface and is a temporary phase. For Sri Aurobindo’s Force works, very often so invisibly that none can perceive the subtle current, and it produces an unexpected result illumining all darkness and years of patient waiting. Such is the import behind the journey of Sri Aurobindo’s relics to Bengal and its sudden electric effect.

Sri Aurobindo came away from Bengal as suddenly as he had chosen her for his field of activity. So one might say that he completely forgot his past, a greater spirit have called him to a higher mission. One might declare that his consciousness saw the world as a battlefield to be conquered for God, and Bengal could be no more than a faint dot on the map of his new dynamic vision. I do not view these things in that light. Sri Aurobindo did not easily forsake anything that had once touched his heart and drawn out of it the hidden divine spring. He became the God-man, but the man in him never ceased to nourish, however dimly, the child-flame that he had himself kindled. He always kept in touch with Bengal’s destiny and followed closely her passage through a long tunnel of darkness and despair, never failing to respond to her soul-call in times of dire peril. His casual remarks bear testimony to the fact. When, after the partition, somebody apprehended a great calamity facing the Hindus of Bengal, Sri Aurobindo said, “Do you think that a population of three and a half crores can be wiped out from the earth?” At another time when the Hindus were submitting meekly to all sorts of repressions and became panicky before the orgy of massacre, his spirited comment was, “Since when has Bengal become so weak and effeminate?” Soon after this, an unseen Force came into play. He had seen Bengal’s plight, her division, the demoniac communal upsurge and, even before that, the war-cloud threatening her with invasion, betrayal, destruction, famine and starvation. Prayers for help had incessantly poured in from the representative souls of the mighty race fallen into disgrace. He had sent ungrudgingly his potent spiritual force to the people in distress.

But how many have perceived his invisible Hand? Sceptics may be found who will declaim, “If the hand was there, it was most ineffectual, for the burden of our misery has piled up instead of going down.” Miseries have increased because Bengal has turned her back on her dharma, has denied her Saviour and fallen upon the flesh-pots of power as her true sustenance. No doubt, various factions with their inevitable fruits of bale have brought down the high crown to the mire. When Sri Aurobindo was asked, “Why is Bengal so much in travail? In the forefront of all battles and new movements, why today is she the battle-ground of parties and leaders?”, he remarked, “Because there is no leader.” “So long as there is no leader, will she go on in this way? Is there no prospect of any such leader coming up? Where is he to come from?” “If there is an aspiration for it, the leader takes birth,” was the surprising reply.

No leader seems to have been born, since the aspiration was wanting. And Bengal has no longer turned out heroes and Fiery dreamers but self-seeking men who have claimed power and enjoyment as the reward of sacrifice. Hence the country’s decline. The Shakti withdrew behind the veil and, working imperceptibly, began to prepare, from within, the silent change. The aspiration that had died has revived and grown under the harrow of suffering and a new Dawn has burst upon the horizon. For, behind this huge mass-rally, we see once more the heaven-ascending call of the Swadeshi days, and Sri Aurobindo has responded. We see before our mind’s vision Bengal leaping triumphantly towards another new birth, not by any means a political, but a spiritual renaissance. Behind Bengal’s apparent decadence this was the secret divine purpose and we firmly believe it was Sri Aurobindo’s invisible and right guidance that has led Bengal to this hour of God.

Whatever the appearance we must bear,

Whatever our strong ills and present fate,

When nothing we can see but drift and bale,

A mighty Guidance leads us still through all.[1]

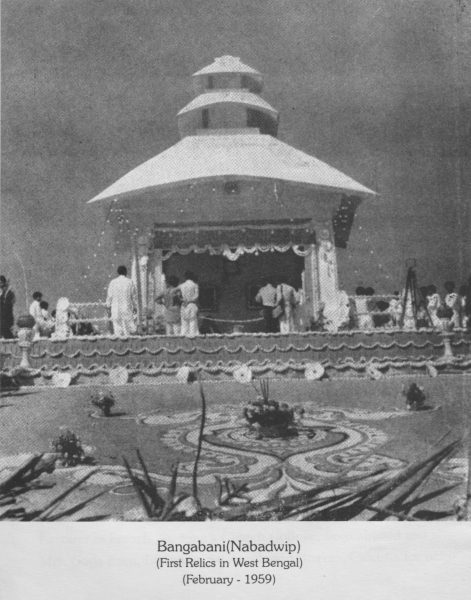

Therefore the Divine Shakti, the Mother, sends with her own hands of radiant Power Sri Aurobindo’s relics to Bengal, and Her inspired children pay homage to them in an unprecedented manner. These relics are Bengal’s leader, master and saviour. For what are relics? A piece of bone, a piece of nail or hair simply to be kept in a casket and worshipped like an image? Is it not said that out of the bones of Dadhichi was made the thunder of the gods? The relics of the Avatar are charged with that divine thunder which is sure in its work and tremendous in its self-effectivity. It will work slowly or fast as the instruments handling the power will allow it to move in its cosmic field of action. But work it must, bringing to birth a “New Island” — Navadwipa — in the heart of the old Bengal. Once a primitive island was transfigured by Buddha’s relics thousands of years ago and it has since remained faithful to his teachings. In this “New Island” of Sri Chaitanya appear Sri Aurobindo’s relics, rays of the apocalypt Sun. Bengal has found her Leader.

Reproduced from “Hindusthan Standard”; Reprinted in Mother India, February, 1959; this piece was written on the auspicious occasion when Sri Aurobindo’s sacred relics was brought to Navadwipa (in the district of Nadia, West Bengal, the birth place of Lord Sri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu – Editor)

[1] Savitri p. 59

Sri Aurobindo as Guru

The Upanishads and the Gita have compared the path of yoga with the sharp edge of a razor-blade and have established as an absolute rule that it should not be practised without the help of a guru. With a few exceptions, this strict injunction has been obeyed even to this day. One seeks, waits, prepares oneself, and if one is sincere, the guru comes at the proper time. The traditional experience and teaching have confirmed that “he who has chosen the Infinite, has been chosen by the Infinite.”

The guru once found, many relations are possible between the guru and the disciple, as with the Divine. In effect, for the disciple, the guru is the representative of the Divine on the earth: the relation can be that of father and son, master and servant, lover and beloved, etc. This relation is indissoluble and can cease only with death or with the guru’s permission. The guru takes entire charge of the disciple; he loves him, guides him, protects him like a mother. His only reward is the accomplishment of his sacred trust. Also, not to discuss the master’s directions but to obey him to the letter was an absolute rule to be followed by the disciple.

To illustrate the responsibility of the guru Sri Aurobindo recounted to us an anecdote. A disciple, wanting to be a guru, sought his own guru’s advice in the matter. He got the reply: “To your already heavy burden you are going to add another one; for you have to take upon your shoulders all your disciple’s faults, and his sins.” Such was in particular the case of Sri Ramakrishna.

Sri Aurobindo has given to the hoary but still continuing tradition of the mystic tie between guru and disciple a new character. The practice of yoga, while losing nothing of its essential spirituality, has become much more supple. Sri Aurobindo’s yoga being new, the methods and means too must be adapted to the modern spirit. Thus, first of all, Sri Aurobindo allows each disciple a great liberty. He should himself find out his own path, that which suits his own nature. Sri Aurobindo believed that without liberty the soul cannot attain its full development. “You truly give us a long rope!” I told him. “Even if we make grave errors, you simply observe silently, expecting us to approach you for advice.” To which Sri Aurobindo replied, “A long rope is necessary!” And the Mother spoke to the young people in these terms: “All of you, my children, live here in exceptional freedom: no social constraints, no normal constraints, no intellectual constraints, no principles. Only a Light is there.” Rabelais also gave this freedom in his Abbaye, but there was no Light.

At the same time Sri Aurobindo accorded to us the privilege to ask him questions, to have intellectual, literary and yogic discussions with him and follow Ramakrishna’s advice to Vivekananda not to accept anything blindly. The mind has its need to be satisfied. Sri Aurobindo understood the modern mind, its doubts, its intellectual curiosities, because he himself was agnostic for a certain time and suffered from doubt. He never imposed his ideas, but considered everything with largeness, tolerance and sympathy. When somebody behaved badly, we would suggest that he should be either sent away or put in quarantine. Sri Aurobindo would answer with a smile, “Yes, it is a simple remedy, no doubt, and in the outside world it would be fitting. But here we can’t apply it.” On another occasion a sadhak was asked why he did not listen to the Mother; he said, “That is my weakness.” The same sadhak dared to write to Sri Aurobindo a letter of sixty pages — on a different subject! Sri Aurobindo never lost his temper. “Anger is foreign to my nature,” he said. His relation with each individual varied in tone, accent and style according to the nature and each felt the Master near to him. It can be said in passing that when the Mother accepts a disciple, she accepts him as he is, and cannot abandon him for his weakness, because he also has left the world for the sake of sadhana.

It was my great good fortune to have Sri Aurobindo as my guru. In my exploration of spiritual history I have not come across any other guru who can be compared to him. He was not only guru, but also the Divine in a human body, the last Avatar, the supramental Avatar according to the Mother. A synthesis of two cultures, oriental and occidental — poet, philosopher, politician, linguist, literary critic — he was also the yogi who might well say: “I have drunk the Infinite like a giant’s wine.”

My relation with him seemed exceptional to other disciples. None could imagine he would behave with a young novice like an intimate friend.

A medical man, materialist by education, I cared very little for God and had no faith. I started the sadhana without having any idea about it, as Stendhal’s Fabrice joined the army in utter ignorance of what war was like. And out of this raw and sceptic fellow Sri Aurobindo has made a fighter for the Divine. I am going to tell how it was done and, if possible, give at the same time a glimpse of Sri Aurobindo’s life as I have come to know it.

I came to the Ashram at a period when the sadhana was going on in the subconscient, as Sri Aurobindo said to me. The subconscient is like a dense virgin forest; we find a superb description of it in his God’s Labour. From his retreat he was corresponding with all disciples, writing every night for about five to six hours. This period which I have called the correspondence-period lasted about twelve years. Each one related his inner and outer life, asked very often quite ordinary questions, and to all our human follies Sri Aurobindo replied with the patience and solicitude of a god. One day he wrote, “An avalanche of correspondence has fallen on my head.” Another day when I asked back my “hibernating” typescript of a poem, he replied, “My dear Sir, if you saw me nowadays with my nose to paper from afternoon to morning, deciphering, deciphering, writing, writing, writing, even the rocky heart of a disciple would be touched and you would not talk about typescripts and hibernation. I have given up (for the present at least) the attempt to minimise the cataract of correspondence; I accept my fate like Raman Maharshi with the plague of prasads and admirers, but at least don’t add anguish to annihilation by talking about typescripts.”

All were surprised to find that Sri Aurobindo took up this familiar and humorous tone with a fresher, and were even shocked, for was not Sri Aurobindo the incarnate godhead, majestic and grave and serene, and should he not therefore be without any taint of humour? During the Darshan his ‘immobility’ inspired an august fear. This was the prevailing conception of a god.

I did not fail to grasp my good fortune with both hands. When the Divine gives himself, one has only to accept Him to the full. I asked him all sorts of questions from the most profane to the sublime, and he satisfied them in a simple, familiar style, always with an incomparable indulgence as if I was a prodigal son, though most of these questions had already been answered in his works. Thus our correspondence swelled up, striking many notes, sometimes sounding like a trumpet, sometimes murmuring sweetly like a stream, often bursting with a divine laughter. When I had a headache, I wrote:

Guru,

My head, my head,

And this devil of a fever!

I am half dead!

Sri Aurobindo replied: “Cheer up! Things might have been so much worse. Just think if you had been a Spaniard in Madrid, or a German communist in a concentration camp. Imagine that, and then you will be quite cheerful with only a cold and headache. So

Throw off the cold,

Damn the fever,

Be sprightly and bold

And live for ever.”

Another time I asked him what Brahmic consciousness was. In a light vein he explained to me a profound truth:

“Eternal Jehovah! you don’t even know what Brahman is! You will next be asking me what Yoga is, or what life is, or what body is or what mind is, or what sadhana is!….

“Brahman, Sir, is the name given by Indian philosophy since the beginning of Time to the one Reality, eternal and infinite which is the Self, the Divine, the All, the more than All, which would remain even if you and everybody and everything else in existence or imagining itself to be in existence vanished into blazes — even if the whole universe disappeared, Brahman would be safely there, and nothing whatever lost. In fact, Sir, you are Brahman, and you are pretending to be Nirod; when Nishikanta is translating Amal’s poetry into Bengali, it is really Brahman translating Brahman’s Brahman into Brahman. When Amal asks me what consciousness is, it is really Brahman asking Brahman what Brahman is. There, Sir, I hope you are satisfied now.

“To be less drastic and refrain from making your head reel till it goes off your shoulders, I may say that realisation of the Self is the beginning of Brahman realisation — the Brahman consciousness — the Self in all and all in the Self etc. It is the basis of the spiritual realisation, and therefore of the spiritual transformation, but one has to see it in all sorts of aspects and applications first….”

Thus from these letters were born two small volumes of Correspondence, containing side by side literary, medical, spiritual and even political questions. Audaciously, following Vivekananda’s example, I tried to argue with him and even dared to differ on points about which my knowledge was as much as that of a village schoolmaster. But he suffered all my foolishness, my impertinence and never uttered a hard word or showed bad temper, only a sun-like magnanimity. I wanted to have with him the father-relationship — as particularly the lady-disciples did. But he refused sharply, saying, “Let the ladies father me as much as they like. The ‘father’ has a Jewish and Hebrew odour, that I don’t like much.” Later on when I asked him why I was exceptionally favoured, he said, “Find out for yourself.”

It seemed he wanted to “intellectualise” me, but alas, he must have found that my grey matter was no better developed than a rabbit’s. But he did succeed, thanks to this special relation, in drawing me out of the chronic pessimism and doubt from which I suffered quite a lot. I wrote to him, “Your grandeur, your Himalayan austerity frightens us.” To which came the vibrant reply: “O rubbish! I am austere and grand, grim and stern! every blasted thing I never was! I groan in an un-Aurobindian despair when I hear such things. What has happened to the commonsense of all you people? In order to reach the Overmind it is not at all necessary to take leave of this simple but useful quality. Commonsense by the way is not logic (which is the least commonsense-like thing in the world), it is simply looking at things as they are without inflation or deflation. Not imagining wild imaginations — or for that matter despairing ‘I know-not-why’ despairs.”

This magnanimity, this sunny humour at last chased away the Man of Sorrows who had taken shelter, like the Panis of the Vedas, in my subconscient. The force was of course there working constantly, but what I felt was the joy of rasa of life engendered by the inimitable humour. I was tempted one day to ask how two incompatibles, humour and yoga, could so unnaturally combine in him. His reply was the Upanishadic: “He is indeed the veritable rasa.”

This relation, however, did not mean that I was dearer to him than the others. He would not be divine in such a case, for the Divine is samam Brahman, equal and impartial to all, He gives himself entirely to all, only the relation differs according to each one’s need, like the relation of the mother with her own children.

My intellectual preparation glided insensibly into creative activity. I wanted to be a poet. I had started writing in Bengali, then in English. There too my talent was green as a cucumber. But this didn’t matter, for Sri Aurobindo said that in the Ashram atmosphere a creative force was in action that could serve anyone’s aspiration to be a poet or artist. Every day he not only sent me inspiration but corrected my poems, gave concrete suggestions, explained the meaning of the poems which I composed without understanding what they meant. Strangely enough in both Bengali and English I wrote, medium-like, many such poems, some of which Sri Aurobindo called surrealist-mystic. Many times I was on the point of throwing up the sponge since the inspiration got blocked or the result was not to my taste! But always his letters, persuasive like the wind, pushed me on till one day he cried out, “The poet is born. What about the yogi?” And he wrote to me this letter:

“As there are several lamentations today besieging me, I have very little time to deal with each separate Jeremiad. Do I understand rightly that your contention is this, “I can’t believe in the Divine doing everything for me because it is by my own mighty and often fruitless efforts that I write or do not write poetry and have made myself into a poet?’ Well, that itself is ‘patient, magnificent, unheard of. It has always been supposed since the infancy of the human race that while a verse-maker can be made or self-made, a poet cannot. ‘Poet a nascitur non fit,’ ‘a poet is born, not made’ is the dictum that has come down through the centuries and was thundered into my ears by the first pages of my Latin grammar. The facts of literary history seem to justify this stern saying. But in Pondicherry we have tried not to manufacture poets but to give them birth, a spiritual, not a physical birth into the body. In a number of cases we are supposed to have succeeded — one of these is your noble self — or if I am to believe the man of sorrows in you, your abject, miserable, hopeless, ineffectual self. But how was it done? There are two theories, it seems — one that it was by the Force, the other that it was by your own splashing, kicking, groaning, Herculean efforts. Now, Sir, if it is the latter, if you have done that unprecedented thing, made yourself by your own laborious strength into a poet (for your earlier efforts were only very decent literary exercises) then, Sir, why the deuce are you so abject, self depreciatory, miserable?”

We see then that Sri Aurobindo was not only a poet but a creator of poets as well.

We were at this stage of our collaboration when, in 1938, a grave accident happened to him and we were brought face to face. In the small hours of the morning we found him lying on the floor of his room. He seemed to have been in that condition for about an hour without having called any one. He had tried all sorts of manipulations with the leg, but all in vain. The Mother felt in her sleep the vibration, and came up to find Sri Aurobindo in this state of immobility. She perceived at once what had gone wrong and sent for the doctors. After a series of examinations it was decided that the right femur had got badly fractured and that Sri Aurobindo should be kept in bed for some months. One can understand how the news shocked the whole Ashram. What struck me most was that while the Mother was discussing with the doctors all about the accident and its treatment, Sri Aurobindo listened in silence and accepted meekly like a child all the necessary medical prescriptions approved by the Mother. That was a lesson in submission to all of us. The doctors had observed that Sri Aurobindo was an ideal patient.

The accident compelled him to abandon his solitude and accept the help of his disciples for medical reasons. Even after his cure, our services were retained.

Truly speaking, I had nourished in my secret heart a desire to see him from near at hand, hear his voice, talk with him and if possible serve him. Perhaps our correspondence pushed me to this utopian reverie. But when we actually met, no sign of recognition on his face! It was as if we had been unknown to each other — or too well known? His attitude towards all of us was most impersonal to start with.

During the two or three months of his illness, he kept his unperturbed calmness and good humour. Neither the gravity of the accident nor its inconveniences affected him in any manner. He told us later on that before the accident he could change pain into joy, but the suddenness of the accident and the intensity of the pain made him powerless for the moment…. He did succeed afterwards. He said also that the accident, the illness etc. were for him only a phase of the inner battle.

We heard very little complaint during the long months of hospitalisation. Not only did he obey all the medical restrictions and physical discomforts with equanimity but lightened our own burden by cheerful talks. The Mother used often to ask, “Are they making you talk?” And his smiling reply was, “Oh, that’s nothing!” For over a year he had only a sponge bath; hunger did not seem to gnaw him; nor did heat unnerve him; he did not seem to live in the body. But he was far from being dry or austere, he was not an ascetic. He enjoyed good food, witty words and slept like all of us. He was not a “puritan god who had made of pleasure a poisoned fruit”; he read newspapers (but not books, for — in Mallarmé’s words — he ‘had read all books’!). He was not lost in meditation, eyes closed and legs crossed. In short, no external evidence would proclaim to us, “Here is the yogi who has reached the Supermind.” People were surprised to hear that his external life differed in no way from that of a common man, simple, natural and healthy. “To be transformed radically within, remaining apparently human without,” such is in effect the principle of his yoga.

And this was amply illustrated by the calm and serenity he maintained even in moments of great disturbance. He taught us that one must be able to keep a perfect equanimity even in the midst of massive destruction. We saw how, during the troubled period of war, he went on with his usual daily activity, never changing the normal rhythm of his life. He attended to his intellectual work. He started rewriting a good deal of The Life Divine soon after his convalescence and finished it in two years. We used to see him sitting on his bed with his pen, papers on the table, but no books. He had forgotten the world with its devastating war-thunder; the words came ‘flowing direct to his pen, as from a hidden silence.’ Now and then he would stop, look in front and dive again. The Mother would come with a glass of coconut water, and wait till he would look up. He needed no books, no thinking. He had stopped thinking long ago — after his Nirvanic experience in 1907 and since then all that he wrote or said or did had come from the higher silence. “To be free from the responsibility of thinking is a great relief,” he used to tell us.

About the second or third volume of The Life Divine, when it came out, he remarked, “It is a huge elephant.” All three volumes, neatly bound in polished white cloth, were sent to him to be blessed with his autograph. On each one he would write the name of the purchaser, add his blessings and his own signature. More than three hundred such copies have conserved his autograph as an act of Divine Grace.

The Life Divine over, Sri Aurobindo took up his epic Savitri. I had the unique opportunity to follow its growth and development from a tiny seed into an ashwattha tree. With an infinite care, exacting at each step a flawless perfection, he worked and worked, slowly, silently like a god in labour. One would gape with wonder to see how many versions he had made of some cantos! At the end when his vision was affected he had to dictate the verses like Milton. I remember that he dictated in successive sittings near about four hundred lines of The Book of Eternal Day. He had made about twelve revisions of the first Book. And he would certainly have done the same for the entire Savitri had he had sufficient time. Many other incidental tasks like correspondence with sadhaks, answering letters from outside, reading of theses, essays, poems and other miscellaneous intellectual tasks took up much of his time till one day he had to speak out: “I find no time for my important work!” Then he began systematically the work on Savitri and we were proceeding finely when again all of a sudden I heard him utter, “I want to finish Savitri soon.” That struck my ear like a sharp slap! It was in 1950, a few months before his passing away. Such an accent was most foreign to his nature. In everything that he did, his talk, his walk, his eating, his dictation, there was not the least haste; he would give the impression as if “all eternity was before him.” “Well then,” I asked myself, “what imperious need could make him impatient, he who was an example of patience and equanimity?” The work was, however, finished somewhat hurriedly and even so some parts were not revised. Afterwards of course we could see in a clear light what had pressed him inordinately.

One can imagine then that his seclusion was neither that of an ascetic’s refusal of the world nor an absorption in samadhi away from life. One might, on the contrary, reasonably ask, “Where in the midst of so much activity was the yogi? In what way was he different from other great men?” Here some understanding of the principle of Sri Aurobindo’s yoga is necessary. It is radical departure from most of the traditional yogas. For Sri Aurobindo all action depends on the consciousness from which it is done. Firmly seated in the divine consciousness one can do any kind of work which will be the reflection or translation of that divine consciousness. So whether in work or in activity, one is always united with the higher consciousness. And Sri Aurobindo’s integral yoga demands that there should be no division between the external and the internal life. All life is yoga. “Do you imagine that when I write to you these letters, I lose the divine consciousness?” he wrote to me. He has also said that so long as one cannot undertake any work with a perfect equality, one is not a yogi. The Mother too says that so long as this division remains in the mind, transformation of life is impossible. Similarly when Sri Aurobindo used to give us inspiration for writing poetry, it was not to make us poets but that it might help us in our sadhana.

Even so, Sri Aurobindo reserved a big part of his daily life for what he called his personal work of concentration. Generally, the whole morning till the time of breakfast, which was gradually pushed to three or four o’clock in the afternoon, he passed in complete silence. None but the Mother was supposed to ‘disturb’ him except for exceptional reasons. We kept ourselves ready behind his bed, talking merrily or reading, while he was seated at ease in the bed, with eyes wide open, absorbed or concentrated God knows on what! His consciousness was “voyaging through strange seas of Thought, alone.”

During this period, he was quite a different person, far remote from that of the Correspondence or of Evening Talks.

This period was perhaps the most mysterious part of his life. Nobody except the Mother had any idea of what he was occupied with. Was he drawing down the supramental Force or concentrating on cosmic problems or even some individual cases needing some special attention? At these moments we were strangers to him: we might be crossing his presence many times, but we had no apparent identity. If he needed something, it was an impersonal voice calling somebody impersonal, as it were, for he would call by any name, and the voice would come from afar, the tone grave, the look elsewhere; the noise, our chatter fell into a vacancy. Even the explosion of a bomb would have left him serene and silent.

On this point the Mother has told us a story. One day when a storm was raging outside, she entered Sri Aurobindo’s room to find that a complete silence was reigning inside. This side of Sri Aurobindo I called the impersonal aspect of his person. People believed that we were all the time talking with him and that his radiant humour was pouring in a cascade and bathing us in its exultant flow. What a surprise to hear that such moments were numbered when he descended from his inaccessible heights to become ‘human’. And this short time was our divine moment. Like bees to the flower we would gather round him. The supramental cloak would slip down from his shoulders to reveal a friend who talked with us without any conventional constraint. Philosophy, literature, politics, yoga, even the most common jokes about snoring or the Sunday-Times trivialities were our fare. No ethical distinction between high and low, right or wrong ostracised any topic, only it must have some rasa in it. On one side his vast knowledge, his prajna was at our doors, on the other many small incidents, hitherto guarded secrets came to us in the form of reminiscences seasoned with light humour. One day he said, “All that I see in this room, these walls, these tables, the books, etc, etc., and yourself, Dr. Manilal, I see all as the Divine. No, it is not an imaginary vision, it is a concrete realisation.” Another day, Dr. Manilal having stopped his own meditation from fear, Sri Aurobindo scolded him mildly and said, “Oh, this fear! Even if you had died at that moment, it would have been a glorious death!” To another who had come out of his meditation he remarked with a smile, “I see your face beaming with a supramental ananda!” Such humour, sweet, refined and restrained, put us on a footing of equality.

But there too, as in all other things, he kept his tranquil spirit, his impersonal way. He never raised his voice, looked down or in front when he talked, and he talked very slowly, did not insist on his point, while a benign sweetness softened his countenance. When he criticised men or countries, there was no contempt or malice in his expression. He saw the Forces of which men are nothing but poor puppets. His divine compassion was over all. The impersonal again saw all with an equal eye.

I have often asked myself how such a division was possible. How could he be both personal and impersonal at the same time? Did he not lose his universality when he became an individual with us in his talks? It appears that one can be the transcendent, the universal and the individual simultaneously. Similarly he could keep an absolute silence in the midst of full activity. His luminous verse, “Force one with unimaginable rest,” gives a glimpse of what was a baffling mystery to me. All his activities, political, literary or otherwise, emerged from this Nirvanic silence and none knew it. All the volumes of the Arya had their source in this sovereign silence. And it was this force of silence that caused Hitler’s downfall and India’s independence. “There are two great forces in the universe, silence and speech…. Infinite is the power of this calm and silence, in which the great forces prepare for action.” Let us remember Buddha whose prodigious activity welled out from the ineffable silence of Nirvana!

In this modern age of feverish excitement and dizzy speed, Sri Aurobindo was never in a hurry, he remained calm and unperturbed even in the face of darkest calamities. He had an unshakable faith. His room was, as it were, packed with a concrete silence, but the force, the peace, the joy, the light were also there for anybody to feel and breathe them. During the first years of our stay with him, we were working almost twenty hours a day and yet there was no fatigue! Whence came all that joy and energy, I used to ask myself. I understood only after I had read Kalidasa” epic Kumarsambhava, “The Birth of the War-God.” There the poet describes how Shiva’s two servants were filled with inexhaustible energy that streamed from Shiva’s third eye. Very often we had the feeling that Sri Aurobindo was himself Shiva, or rather Shiva was an aspect of his personality. His total abnegation, his non-attachment to material things, his liberality, universal compassion, childlike attitude, distaste for physical work, his complete surrender to the Mother who looked after him, all these are features that we associate with Shiva. His very body had a likeness.

One can say then that impersonality was the essence of his nature. All that he did, all that came from him, his ease, reserve, calm slowness, even certain aspects of humour gave me that impression. We know that in his political activities he preferred always to remain in the background: one day he said, “The confounded British Government spoiled my play.” He was not even calling us by names when he needed something!

Though impersonal, he was a person and his personal body was so sweet, so tender! A perfume like that of a child’s body emanated from it. His small feet supporting a massive frame were warm like the down of a bird, and his palms were soft and velvety like those of a woman. When he lay down on the bed, his body covered the entire bed, and the trunk, lightly powdered after bath, hair plaited or loose falling down the neck reminded us again of Shiva. Sometimes the body was radiant with a white light. At other times when, seated on the edge of the bed, he waited for the Mother’s coming, his majestic posture evoked the figure of Moses. The portrait of his last days is nothing but a travesty of this supreme grandeur. Sri Aurobindo has said that the Supreme is both personal and impersonal at the same time. His own life is a luminous example of this truth and has given me a small insight into the working of the Divine in the world. We had the unique opportunity of seeing two personalities together, the Mother and Sri Aurobindo, the Shakti full of energy, dynamism, Shiva, impassive, immobile; the Prakriti, the Purusha, two-in-one.

This impassivity was, to my shocked surprise, one day suddenly snapped when he uttered, “I want to finish Savitri soon.” It is true that during the last phase of his life he became very grave and withdrawn. One of us dared to ask him the reason. He gave an enigmatic reply: “Things are getting very serious!” The meaning was clear only after he had left his body and this he did in a normal manner. An extraordinary phenomenon was observed the next day: the entire body was suffused with a golden light. The Mother said that if the Light remained the body would be preserved in a glass case. But alas, after five days the Light vanished, which is quite in conformity with Sri Aurobindo’s mode of life for he never wanted to capture the world’s imagination by miracles; he was not a thaumaturgic magician.

One can imagine the enormous void created in the Ashram by his unexpected departure. It was a thunderstroke. And if the Mother had I not absorbed the shock I do not know what a formidable chaos would have reigned in our world! She filled the void by her Grace, her power, by her very person. Sri Aurobindo’s absence has brought into the world-gaze the greatness, the supreme power of the Mother. She has, by her love and care, rebuilt the nest badly shaken by the storm. Before his passing, Sri Aurobindo had written in Savitri, “She alone can save the world and save herself,” which clearly pointed to the Mother’s future role.

If Sri Aurobindo is physically absent his subtle presence is yet very near us, alive and active, and as before it is continuously working on to establish the supramental kingdom on earth, “In Death to repatriate Immortality.”

Such was the Master’s life, and such it abides even now, always silent and impersonal, a total self-effacement. We lived the last twelve years of his life following him like a shadow. We saw how much the Divine in the form of Guru, the Avatar, works, suffers for our ‘confounded humanity.’ He has said, “My yoga is not for myself, I need nothing, neither salvation nor anything else, but precisely for the earth-consciousness, to open a way for the transformation of the earth-consciousness.”

We have also watched the tragedy of his passing away in a normal tranquil manner like a common man, not like some yogis who give up the body in meditation. Like Sri Ramakrishna, he took up the disease, allowed its natural course and reached the natural end. His whole life was an extraordinary phenomenon, but its external form so simple, natural and human, so to say, concealed the inner miracle. What we have seen are nothing but a few waves, small and big, on the surface, while his true life was ‘never on the surface’. The depth of that life will always remain unfathomable. The Mother alone knows what he was and what he has done for the world. One day the world will wake up to a recognition and accept him as the Avatar, the World-Teacher.

(Mother India, February 1967)

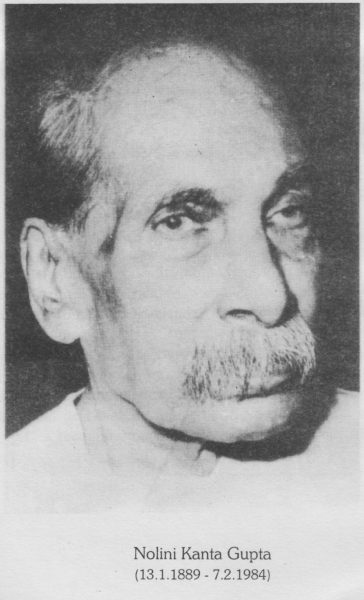

Nolini-da

It was about ten years ago that we assembled in this historic playground of hallowed memories on the occasion of the Mother’s passing and it was Pranab who addressed you at that time. Most unexpectedly it is on the occasion of another departure that we have assembled again tonight. It is the passing of Nolini-da who was, to borrow a happy phrase, one of the first and foremost disciples of the Mother, her collaborator and our eldest brother. The sanctity, solemnity and beauty of this occasion my poor words cannot express though my mind can envisage it without fathoming it. His “unhorizoned” consciousness is too wide for human measurement and it never ceased to climb towards the heights even when he fell ill. At that time I was once called at night. He said, “You see, I went out of my body and when I came back, the body received a jerk. Hence this minor disturbance. You will understand. I don’t need any medicine.” The tone reminded me somewhat of Sri Aurobindo. I had come to know that often Nolini-da used to go out of his body and had to keep his hold on somebody’s hand in order to keep contact with the earth. I had read also the Mother saying that he could easily go out of his body to the Sachchidananda state. Well, these superconscious things are beyond me; I know a bit of the subconscious ones. Nevertheless I feel it my humble duty to present a few glimpses of his vast-visioned life to you so that you may have a rough idea of a person who rarely spoke of himself and to whom you may offer you gratitude and love for having quietly done so much for us. I must confess that most of what I shall say is based on my observation, reflection and conviction.

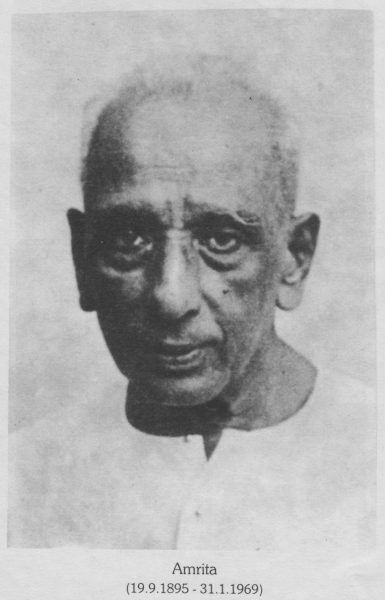

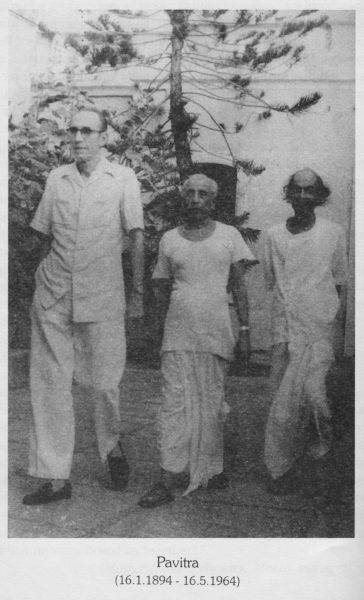

I had a moment’s sight of him when I met the Mother for the first time. She came to see me accompanied by Nolini-da, Amrita-da and Dilip-da. It was Dilip-da who had arranged the interview. Later, when I came to settle in the Ashram for good, I used to hear that Nolini-da was an enigma; he was a man of few words. People would not dare to assail his sanctum except on strict business. He was the secretary of the Ashram, but they all respected his aloofness. Often he used to be brusque with them and there were quite a number of anecdotes current in the Ashram about his abruptness. He had acquired the knack of upsetting people without himself getting upset. I shall quote two such stories. Once a sadhak complained to the Mother for what he considered Nolini-da’s rude behaviour to him. Sri Aurobindo wrote to Nolini-da about it. As a result he called the sadhak and apologised to him. On another occasion the hair-cutting saloon was to be opened. Nolini-da was approached; he flatly refused. The person wrote to the Mother and proposed another name instead. When, next day, Nolini-da went to see the Mother, she asked him why he had refused. On coming down, he hastened to the saloon and opened it. Therefore I used to avoid him. There you can see two traits in his nature, the outer somewhat jerky and the inner obedient to the Mother. Amrita who was his close associate used to say that Nolini-da was like yasti madhu. You have to chew it before you taste its sweetness. What a conversion took place in the later phase of his life! I marvelled at it. But let me not anticipate.

Though I kept myself at a distance, his learning and writings had a great attraction for me. I admired and respected him for them as well as for his personality. His passion for knowledge, which made buying books his one hobby, could be summarised by a verse from Savitri: “He sought for knowledge like a questing hound.” If the small can be compared with the great, I had also such a passion, but a minor one and I tried to satisfy it at Sri Aurobindo’s expense. You know the way I provoked, pestered, even bothered him with a host of questions. While I did this, Nolini-da gathered him in the vast cathedral of his mind and seated him on its high altar as the supreme deity. You know how Sri Aurobindo initiated him in the esoteric lores of the Vedas and Upanishads as well as in the secular knowledge of various literatures and languages. Sri Aurobindo’s heart must have been gladdened to find such a worthy young mind. Thus his approach to Sri Aurobindo was through the mind. I need not dwell at length upon this aspect, since his erudition is quite well known. Perhaps I can summarise it by quoting another expression from our Shastra. Both para vidya and apara vidya were at his command and they have all gone into 10 volumes of Bengali and 8 volumes of English works. They can make a side-stream running along with Sri Aurobindo’s vast Brahmaputra-like productions, fed and nourished by them and flowing into oneness with them. Sri Aurobindo has said that Nolini-da had a remarkable mind. But some people have found its works an echo, a shadow of Sri Aurobindo. Even if they were a shadow, they were a luminous shadow.

I have often wondered how he could contain such “infinite riches in a little room.” For except his broad and high forehead, the other parts of his body were frail. His forehead often made me think of Shakespeare and Einstein. In fact, often during our medical visits in the morning when he had just come down from the inner empyrean as if with the gold dust of trance-land still on his body, a few locks of hair disarrayed, eyes dreamy, he looked very much like a mystical Einstein. But after he had had his wash, combed his hair and brushed his pet moustache, he was the elegant incarnation of Virgil.

Still, he was by no means a book-worm, recluse. He had his hands full. He had to manage the bulk of the Mother’s and Sri Aurobindo’s correspondence, distribute their letters to sadhaks and carry on other work. His domestic chores he did himself: washing his own clothes, making his bed, bringing his kuja-water, preparing his own tea, polishing his shoes, etc. He had a weakness for shoes. When Sri Aurobindo wanted to get rid of a pair of Vidyasagari shoes, having no further need for them, he said they could be given to Nolini since he was fond of shoes. He was a bit of a dandy. He was doing regular athletic exercises and taking part in competitions. Mass drill was his favourite item and he participated in it till his late seventies.

Every fraction of his life was disciplined and methodised. That is the external reason of his keeping fit and being capable of a huge output in a single life. I wonder if mere is any world-figure today with so many facets combined and harmonised to such a degree of perfection. But where is the key to be found for such various accomplishments? It was certainly his inner development that was the secret of his outflowering. He practised yoga with one-pointed concentration and took up his literary and other activities as a part of it. As in Sri Aurobindo’s own case so in Nolini-da’s and in other cases of outer flowering in art, literature, etc. in the Ashram, yoga and the Mother’s and Sri Aurobindo’s force were mainly responsible for success. It seems that during the most brilliant period of the Ashram in 1927, when the Mother was bringing down the gods into the sadhaks, there came down into Nolini-da’s adhara the consciousness of Varuna, the Vedic god of Vastness. Hence the vastness in his writings. One could never achieve such an amplitude and integrality by mere mental labour. The work of the mere mind would be lop-sided. Nolini-da’s later productions, like those of his Master, must have been written from a silent mind. I would say transcribed rather than written. I would have doubted such a process, had not Sri Aurobindo convinced me by his thundering words and logical arguments during our correspondence.

Now I enter a terra incognita. To talk of the inner development of a Yogi is like a layman perorating on the theory of relativity. Fortunately I can draw upon some casual hints given by the Master and the Mother. Once when someone complained that Nolini-da was not doing Sri Aurobindo’s yoga since he kept aloof, was unsociable, etc., Sri Aurobindo replied, “If Nolini is not doing my yoga, who is doing it? Is sociableness a part of yoga?” Secondly, it was alleged that the sadhaks here would count for nothing in the world outside. Hearing which, Sri Aurobindo remarked, “The quality of sadhaks is so low?… There are at least half a dozen people here who live in the Brahmic consciousness…” This statement excited my curiosity and I surmised that Nolini-da must be one of these. I began to study his outer life. I could not get any clue. He was a closed shell, would not expose his pearls to an outsider. Besides, I was just a novice and had not the ghost of an idea of what the Brahmic consciousness was. Apropos of my query I received another sweetly castigating letter from the Master. None the wiser, I went on merrily without caring about Brahman, for Sri Aurobindo was my Brahman till he passed away. And then the Mother filled his place. In the sixties came a startling disclosure from the Mother. She wrote on Nolini-da’s birthday card — “Nolini en route towards the superman.” The years that followed brought a succession of revelations: “Nolini, with love and affection for a life of collaboration” …. “For the prolonged continuation of this happy collaboration” …. and lastly, in 1973, “With my love and blessings…. for the transformation. Let us march ahead towards the Realisation.” These are very big words indeed. I don’t know if any other person received such encomiums. I could now understand to some extent what these expressions meant and I was struck speechless. But Nolini-da swallowed all calmly and with ease. The coming superman did not undermine the natural man. I could not glean his ample inner field. Perhaps he was marching ahead with the Mother and when there was “one more step to take and all would be sky and God,” the greatest calamity befell the earth. The Mother passed away. There was an overclouding gloom, dejection, consternation.

It was then that Nolini-da came forward and took the lead as it were. When the Mother’s body was brought down and laid in the Meditation Hall, the Trustees came and Nolini-da was called from his room. He was requested to say a few words. Keeping quiet for a moment, he stood up straight like a column of light and said some words whose purport is: “Let us stand together and go forward in harmony and collaboration. The Mother has said she will be with us in our consciousness.” He felt perhaps that a vacuum had been made and he must do his part.

From that time a new life began for Nolini-da and a new phase for us. He had to come out of his shell. All eyes were turned to him for guidance, for help spiritual and mundane. He was invited to witness many functions; his approval was sought in many activities. In other words, he was called to shoulder a big part of the Mother’s spiritual work. A plethora of visitors asked for his touch. His writings were continuing in the same way and he used to read some of them in the School, in the Playground and in the Meditation Hall in front of his room. The idea, I believe, was to hold the Ashramites together and bathe them in the spiritual Presence. The Mother had assigned to him a French class for the elders and he continued it. In this manner, he was coming out more and more and his presence and nearness were available. It will not be an exaggeration to claim that he held the divisive tendencies together and saved us from falling apart. His hold particularly on the youth was of very good augury. When he had to undergo an operation for a cataract, the young boys kept vigil over him for about three months. Strange enough to observe that people operated upon along with him or afterwards got cured in two or three weeks while he took three months or so owing to a number of complications. He remarked jocularly that because he was given so much attention Nature took revenge.

In 1977, he had an apocalyptic vision of the Mother. He writes: “The Mother says, ‘Just see. Look at me. I am here come back in my new body — divine, transformed and glorious. And I am the same Mother, still human. Do not worry. Do not be concerned about your own self, your progress and realisation nor about others. I am here, look at me, gaze into me, enter into me wholly, merge into my being, lose yourself into my love, with your love; you will see all problems solved, everything done. Forget everything, forget the world. Remember me alone, be one with me, with my love.”

It was after this vision probably that he began to talk more and more about the Mother. To the departing students of the Higher Course he used to repeat that the Mother would be with them wherever they went. They were bound to her by a golden chain.

In 1978 either due to overstrain or some other reason he fell ill. Dr. Bose, Dr. Datta and myself formed a trio. I was the zero of the three, for my presence was more of a personal nature than a professional one. Now we enter the last phase of Nolini-da’s long career. It is a sweet song telling of sad things. His heart had gone wrong; to use Sri Aurobindo’s words, it was misbehaving. The blood pressure was high. The doctors succeeded in stabilising them. Satisfied with the progress Dr. Bose went to his home-town for about a month. After he had returned, there was a recrudescence of the symptoms and the condition took a serious turn. Consultation with an outside physician was thought of but Nolini-da had confidence in his doctors and vetoed the idea. However, things were becoming critical. Nolini-da himself said that he was passing away. The Calcutta people were informed. Somehow the faith and energetic intervention of the doctors, particularly of Datta, called down the Mother’s Grace and Nolini-da was sent back form the threshold. A slow recovery followed and along with it he took up gradually his previous work, but naturally modified according to his measure. His movements were now confined to the Ashram precincts. Apart from the recording of Savitri, translating it into Bengali, seeing visitors and various other minor activities, most of the time he used to keep to his bed. We were visiting him as usual. At this time or even before, I do not remember, my stock shot up with him, though I was only a pulse-taking doctor. He used to call me by name, “Nirod”, which had an Aurobindonian ring, and, stretching his hand, ask me to feel his pulse. Often he used to do that and ask: “All right?” When all of us had examined him, his query was again: “All right?” “Yes, all right, Nolini-da,” we would answer and depart.

No superfluous talk. Sometimes he would simply give a steady look and then utter, “Bonne nuit.” From Datta he would inquire about his patients or he would himself speak of some patients who had approached him. Monique, the French Ballet teacher, had a very bad fracture and had to be sent to France. Nolini-da used to inquire about her almost three times a day.

After that massive attack he never enjoyed sound health and was kept on drugs which he used to swallow without any murmur. Anima would exclaim that she had not seen any other person taking 4 or 5 bitter drugs a day as if it was a habit. When the symptoms increased, I being near at hand was called at night and, if necessary, the others were informed. At times all the three medicos were present. In addition to his own troubles, occasionally Nolini-da used to groan in sleep as if in pain over the ailments of his friends. Once he cried out repeatedly a person’s name. That person appeared to have been in a very critical condition that night and Nolini-da’s body received the vibration. There are numerous instances to show that he was sensitive to other peoples’ inner and outer condition and perhaps sent help to them in the yogic way. I know how in one case he cured an “incurable” malady or at least arrested it completely. He had given peace and taken away deep sorrow from people.

A woman had come from London and wanted to have Nolini-da’s darshan. She was asked to take my permission. I saw her coming back from the darshan with tears streaming from her eyes. I wanted to know the reason. She said that when she had got up after pranam, she was flooded with light coming down upon her. She was permitted to do pranam to him every day from a distance. This was the first concrete proof I had of his spiritual communicative power and my solar plexus was knocked out.

A few months before his passing, Dr. Bose suddenly passed away. Nolini-da was deeply moved. With tears in his eyes and a choked voice, he murmured: “What a fine soul! what a fine soul! He should not have gone before me.” Such human expression of feeling from him was something new to us. I believe that the loss made a dent in his heart. Once Bose had seen in a dream Nolini-da’s upper body full of golden light: the lower part had been absent. Nolini-da commented that, it was an overmind vision. A few days later, as he was lying in his bed, I asked him through Anima where his consciousness could be. He answered: “Why, with the Mother!” I wanted more precision. Then he answered: “In the Overmind.” I was simply swept off my feet. Though the Mother had indicated it, the information coming from Nolini-da himself had a tremendous effect upon me — I don’t know how people in general would understand the significance of that large utterance. Quietly I went away and tried to absorb the impact, for I knew by that time what it meant and at once in a flash many of his actions or decisions which had puzzled us were revealed in a new light. He was suspected to have some weakness for his family. He replied: “Great souls are beyond such ties.” For the first time in our knowledge he had made a personal reference. We were also baffled by his attitude towards those who were known to do harm to the Ashram. Then, when I saw him distributing his own photos to selected people, I was piqued. Now all these bizarre-looking movements troubled me no more and every question was set at rest. The mystery and mystique of all his actions became clear to me. Later I learned from Anima that Nolini-da had confided in her that he was mostly in the Overmind but at times a little beyond it.

To resume, yet cut our story short: Bose had gone from the doctor-group, two were now in harness, Datta’s being the main labour — I was an adjunct. Nolini-da was comparatively well and we expected that he would score his century. Anima and Matri Prasad, his two closest attendants, were regaling him with many stories and he too was indulgent to them. They were very free with him and would cut jokes again and again. I myself used to feel embarrassed at times; for this image of Nolini-da was a new development and I kept always my old attitude of respect towards him. In this period, which was a little before Bose’s departure, his most memorable action was to go and see Vasudha on her last birthday. We were somewhat alarmed. She had been bed-ridden. Nolini-da would often inquire about her and Datta kept him informed. I think Nolini-da had realised that Vasudha’s days were numbered. So he took this opportunity, though he could hardly walk even a few steps. We had great difficulty in putting him in a car and getting him just across the road. He sat before Vasudha with his chest heaving from exhaustion, took her hands into his own, blessed her and then came back.

His Bengali translation of Savitri had been completed and was expected to come out before his next birthday. Since the last months of 1983 things had begun to take a bad turn. His old pain in the heart re-appeared, stringent measures had to be taken regarding seeing visitors and other activities. His birthday on January 13 which had been expected to be a day of jubilation passed quietly, but he did not fail to meet the out-going students and give his blessings. Pain and distress were now on the increase. All modern measures were adopted, but only with momentary relief. Again the question of consulting a known heart-specialist was thought of, but met with disapproval. Distress and agony pervaded the general picture. We were at constant call and the attendants were ever vigilant, particularly at night. Less than a week before the last act, Nolini-da said to Anima that he would like to distribute his Savitri translation to all the attendants. Books were a bit late in coming. He ordered: “Get the books quickly and call the people.” This was the last gesture. As Savitri was Sri Aurobindo’ last composition, its translation has added a large dimension to the Bengali language. When more than once doubts were raised about the exactness of some words, Nolini-da said with force: “One has to read the Vedas, Upanishads, Mahabharata, Sanskrit literature before questioning their use.” He surprised me by this unusual self-estimation.

On the 7th February the closing scene was enacted. We had examined him in the morning. The condition, though bad, was not critical. At noon, I heard that he had taken his usual meal and relieved himself. Datta was by his side. I was suddenly called at 4 p.m. and informed that after the motion Nolini-da had collapsed. When I came down, Datta said with a gloomy air that there was a sudden fall of blood pressure. Nolini-da had gone within; his eyes were shut; the pulse was thready and he was sweating profusely. The end was near. I sat by his side and called “Nolini-da!” his opened his eyes, gave a look of recognition as if from the Beyond and closed his eyes. Slowly, quietly, the breathing stopped at 4.42 p.m. — the grand finale of the long epic story.

Once I had collapsed due to a sudden fall of blood-pressure. Nolini-da was informed that I was passing away. He came to see me and found that I had revived. He seems to have remarked later that I couldn’t go away, I had still a lot of work to do. I suppose, one of the assignments was to help in his departure.

The day after the event, his body was laid out in the Meditation Hall. Hundreds saw his chiselled face embalmed in a Nirvanic peace.

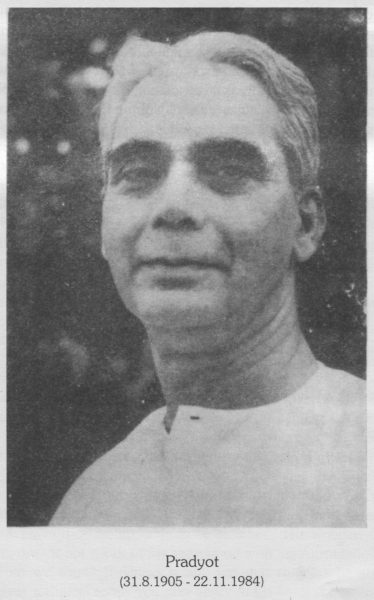

The rest of the story is well-known. One thing to be observed is that his body was taken to the Casanove garden in royal splendour. The procession of cars was something new in the history of Pondicherry. And almost the entire Ashram and group of visitors made their pilgrimage to the burial place as a token of their love and respect. That too was something unprecedented in our experience. A man who had lived a quiet, unassuming life and earned the veneration of thousands. The body was laid to rest by the side of his old friends and colleagues. Amrita-da and Pavitra-da, fulfilling his last wish.

Now when I ruminate over what I was given to observe of the last phase of Nolini-da’s life, a few rare qualities remain impressed upon my memory and reveal to me his true soul. First, his freedom from the taint of personality: ego was dead. He had love for all and sundry. Enemy he had none, not even those who were considered to be doing harm to the Ashram. He accepted them all as the Mother’s children and left it to her to judge them. In consequence he gained universal respect and confidence. The government also had trust in him and the Prime Minister stated that he radiated peace.

Secondly, he always preserved a strong strain of impersonality even with those people who were close to him. That was his natural genius. This was a typically Aurobindonian stamp. The other Aurobindonian stamps were: he would not push himself to the front and never interfered with what people did, even when they happened to be his near ones, unless approached for advice. He never criticised anyone and did not approve of anyone making criticisms and using strong language. A large liberality, sweetness and compassion crowned all his actions and movements. Even children used to love him. If he did not approve of anyone’s actions, he did not confuse the man with his actions. He could invite the man to sit by his side.

These were the later manifestations of his hidden nature. Once somebody complained to him about life and its difficulties. He answered: “Why am I here?” Then the person who had complained said: “You are needed for the Ashram. Therefore the Mother has kept you here.” In a grave tone Nolini-da declared: “I am here for a particular development. So far in my evolution there was the sattwic consciousness: the element of knowledge. Now a new element has been added: love, ananda. For that new growth I am here. But no use saying all this. People won’t understand and they will distort it.”

Some of his last utterances are worth recording. I was once called at night and found him sitting on the edge of his bed. He said: “You see, this body is of the earth earthy and will mix with the earth. But the realisation will remain.” Then in the last days he used to be in-drawn. We thought he was sleeping. When he came out of his absorption he had the appearance of an ever-joyous child and he also spoke and behaved like one. I said: “Perhaps you are in the Sachchidananda state” — to which he replied with a smile: “It is in an Anandamaya region.” On another occasion he was heard to mumble in an absorbed way: “Sat-yogi, Sat-yogi.” Asked whether he was by any chance referring to himself, he softly whispered: “Yes.” After that he withdrew almost wholly into himself, and when he spoke, it was to tell many that he would be leaving his body. On his 95th birthday he remarked. “This new year will be very critical for me.” When he was once asked where he would be after he had left his body he stated very clearly: “A little beyond the Overmind.” During those days he had also visions of three goddesses Chamunda, Kali and Gauri. About Chamunda, he said that she was trying to do mischief with his heart and he had detected it. Kali was all dark: everywhere there was darkness. In another vision he saw that he had gone away to a solitary place, all alone: there was no sign of life anywhere around. Then he saw Matri, following him.

When I try to assess his contribution to the sum-total of the Mother’s and Sri Aurobindo’s work, I feel that, short of the Supermind, he realised in himself a true synthesis of Sri Aurobindo’s Yoga and proved that this many-sided, complex, comprehensive Yoga is not an insane chimera. Further, he has made the path easier and smoother for posterity, as he has himself said that his realisation will remain. He serves as a bridge, an intermediary between us and the Mother. I can illustrate this point by citing the experience of a young sadhika the very night Nolini-da passed away. She went home with a heavy heart after seeing Nolini-da. She read a few pages from The Yoga of Sri Aurobindo before going to sleep. She dreamt that Nolini-da’s body had been shifted beside the Mother’s room on the second floor. People were going to see him in batches. When she arrived, she saw Nolini-da standing at the door radiant, youthful and full of zest. He called her in and cried loudly: “Come, come, today is my Bonne Fete.” Then he made her sit down and talked a lot on the Mother and Sri Aurobindo. Simultaneously she saw his dead body lying beside the wall, as it had been in his room. She was very much astonished. Then she read a chit from Counouma, asking her to go to Cazanove, since she was one of the attendants, and a vehicle had been arranged for the purpose.

Let us try, therefore, to be Nolini-like, to quote K.D. Sethna, if the Mother and the Master seem far beyond our reach.

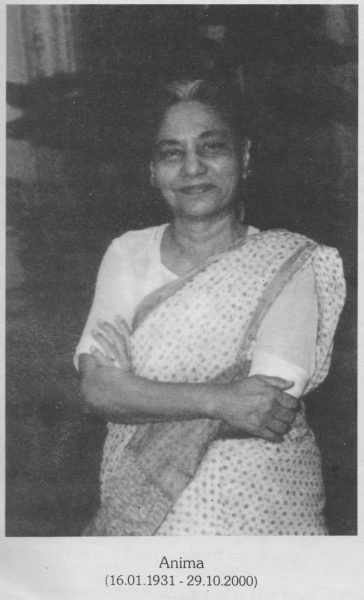

Finally, my story will be incomplete if I fail to recognise the inestimable service rendered by our young people to whom we cannot be too grateful for what they have done night after night, specially Anima and Matri. Anima’s devotion and self-abnegation will be a matter of history. For years she looked after Nolini-da-his secretary, nurse, mother, sister all in one. As soon as he called “Anima”, she was there. She gave him all the royal comfort and ease he deserved. She may have her faults — who is free? — but, without her, Nolini-da would have left us long ago and in a very lamentable condition. Our admiration for her knew no bounds. She kept her eyes upon the comfort of the attendants as well. She was full of life and cheer and had a fund of tales, anecdotes, reminiscences by which she tried to enliven Nolini-da’s mood and mitigate his physical distress though she herself had high blood-pressure and was subject to headaches, pains and other ailments.

In conclusion let us hear a part of the recorded voice of Nolini-da where we get a clue to his true being. (svarupa):

“The story is after all the story of our adventure upon earth, a common adventure through centuries — not only through centuries but perhaps from the very creation of the earth. It is the story of the adventure of a group of souls, souls who were destined, who were created for the advent of a new creation. I will speak of only just a few bits and some important episodes of this adventure in which I participated, because you wanted to hear my life.

“We came, all of you, all of us who are here, most of them, in different epochs at the crucial stages of our evolution. In different periods, whenever there was a necessity of an upliftment or an enlightenment, we all came together, each in his own way. So one or two episodes like that I can tell. For example, in Europe a crucial turning-point of its history was the Renaissance, the new light. At the time of the Renaissance we all know that the creator of the Renaissance was Sri Aurobindo — Leonardo — and the whole Renaissance was his consciousness and all those who flocked around him, each one did his own work. You know that Amrita was intimately connected with that work — he was Michael Angelo. And Moni was also there — Suresh Chakravarty. He was one of the chief artists. I have forgotten his name…

“But all… the work they actually did, you know, the important thing, the consciousness they brought — expressed some sad event, some not so, but living concretising the consciousness…. My contribution in that age of Renaissance was in France. The Mother always said: ‘Your French incarnation was very prominent, even today it is very prominent.’ That little bit of evolution is still living. The consciousness at that time in France — that was also the beginning of the Renaissance and… the new creation, new poetry — I was a poet of that time and introduced the new poetry in France. At that time the king of France was Francois Ier. was in the political — also in the general life of the people he introduced this new light, new manner of consciousness. So I was with him. And who was Francois Premiere you know — Duraiswamy!

“The consciousness of the reality of that country was so strong that when I started reading or writing French — I wrote French — then sometimes I noted down some lines…. later I found that I had noted down exactly some verses of this poet of France, Ronsard…”

I may add an incident of recollection by Nolini-da of a past life. One day when he went to inspect our School garden, he was very much interested in observing the plan of the garden, the trees, the lotus pond and he remarked: “I was the gardener of Louis XIV, Le Nôtre.”

(Mother India, April 1984)

“Old Long Since” – Some Memories of Amrita

In this month falls the birth anniversary of our unforgettable and incomparable Amrita whose sudden passing away was felt as a sharp stab from the hand of the unseen forces. What we miss most in his absence is his Birbal-like wit and humour that used to ‘scatter like sparks from an unextinguished hearth’ at all moments and in any situation, either while plunged in his managerial work, talking business with people, going for a bath, on the way to the Bank, while waiting for the Mother, or even in Her presence. He was the one person we knew who could cut jokes with her while the rest of us were petrified into reverential silence. The Mother allowed him that liberty, and enjoyed his humour, sometimes with an appreciative smile, sometimes with an assumed gravity, and even provoked his playfulness.