I

“These are they who are conscious of the much falsehood in the world; they grow in the house of Truth, they are strong and invincible sons of Infinity.”

— Rigveda, VII.60.5

1893 — a memorable year! It was in 1893 that Sri Aurobindo came back from England to fight for the freedom of India and release her imprisoned godhead, and Vivekananda sailed for America carrying with him the light of the Vedanta to the benighted humanity of the West. What was Sri Aurobindo thinking, what were his feelings as he came in sight of his beloved motherland? When he had left India, he was a mere child of seven, perhaps unaware of the heavenly fire smouldering beneath his sweet, angelic exterior. And when he returned, he was a young man of twenty-one, burning to realise his dreams and visions. These fourteen years, the most impressionable and formative part of his life, were spent in the West in the heyday of its scientific civilisation. We have already seen that Sri Aurobindo’s mind was nourished and developed by the classical spirit in Western culture, and his poetic sensibilities were set aglow by the superb creations of the Western Muse. But his soul remained untouched, his heart’s love flowed towards India, and his will flamed to fight and suffer for her freedom.[1] He did not then know much about India, but he felt a mysterious pull towards her, an irresistible attraction which his mind could hardly explain. “It was a natural attraction”, he said later, “to Indian culture and ways of life, and a temperamental feeling and preference for all that was Indian.” So, his thoughts and feelings converging on India, Sri Aurobindo approached the destination of his return voyage.

And how did India receive her beloved child? What gifts, what presents had she kept ready for him? She bestowed upon him, as an unsolicited grace, one of the brightest gems of her immemorial heritage — a high spiritual experience! In the midst of the confused hum and bustle of the strangers swarming up and down the gangways, “a vast calm descended upon him… this calm surrounded him and remained for long months afterwards”. In this connection, he once wrote to a disciple: “My own life and my Yoga have always been, since my coming to India, both this-worldly and other-worldly without any exclusiveness on either side. All human interests are, I suppose, this-worldly and most of them have entered into my mental field and some, like politics, into my life, but at the same time, since I set foot on the Indian soil on the Apollo Bunder in Bombay, I began to have spiritual experiences, but these were not divorced from this world but had an inner and infinite bearing on it, such as a feeling of the Infinite pervading material space and the Immanent inhabiting material objects and bodies. At the same time I found myself entering supraphysical worlds and planes with influences and an effect from them upon the material plane, so I could make no sharp divorce or irreconcilable opposition between what I have called the two ends of existence and all that lies between them. For me all is Brahman and I find the Divine everywhere.”[2]

That was the characteristic way in which India greeted her son when he returned to her bosom after a long sojourn in a foreign land. This greeting was at once a symbol and a prophecy. It was an index to the glory of his life’s mission.

This sudden and unexpected spiritual experience that invaded and encompassed Sri Aurobindo recalls the somewhat similar — only it was less unexpected — instance of Sri Chaitanya’s conversion in the temple of Vishnu at Gaya. An arrogant young pundit of exceptional intellectual attainments and justifiably proud of his matchless erudition, Sri Chaitanya (he was then known as Nimai Pundit) stood in front of the image of Vishnu’s feet, in the shrine, gazing at the image, and rooted to the spot. A huge wave of devotion surged up within him. It swept his whole being. It overwhelmed him. His body was seized by a violent thrill and trembling, and tears of uncontrollable emotion streamed down his cheeks. It was an experience as sudden and strange in its onslaught as transforming in its result. Nimai Pundit died at that mysterious instant, and out of him rose a new man, a modest and humble lover of Vishnu, a God-drunk apostle of Bhakti.

In Sri Aurobindo’s case, as has been said above, the experience was even more unexpected, for he had no knowledge of the Hindu Shastras. He had neither any desire for yogic experiences nor any knowledge of them. “I had many doubts before. I was brought up in England amongst foreign ideas and an atmosphere entirely foreign….The agnostic was in me, the atheist was in me, the sceptic was in me, and I was not absolutely sure that there was a God at all….”[3] Once, in a letter to a disciple,[4] he referred to a pre-yogic experience in London, but he did not describe its nature. The experience he had at the Apollo Bunder can, therefore, be taken as the first authentic yogic experience that came his way — unbidden but decisive — as a gift of Grace, a bounty of Mother India.

Sri Aurobindo returned alone from England, and his two elder brothers remained there for some time. Then, the eldest brother, Benoy Bhusan, came back to India and obtained an employment under the Maharaja of Coochbehar. He sent some money to Manmohan, and the latter also returned. Manmohan was at first appointed Professor of English at the Dacca College, and subsequently at the Presidency College of Calcutta, which was, at that time, the best college under the greatest University in India. A few words about the brothers and sister of Sri Aurobindo will not be out of place here.

Benoy Bhusan, the eldest, was of a practical but generous nature. In order to relieve the financial strain under which the three brothers had been labouring in England on account of the irregularity and subsequent stoppage of remittances from their father, he had taken a job as an assistant to James Cotton who was secretary of the South Kensington Liberal Club where the three brothers had been staying. Manmohan makes a rather amusingly sarcastic reference to his elder brother in one of his letters to Laurence Binyon: “At last to my joy my brother came to see me, who, as you know, is a very matter-of-fact person, with a commercial mind, a person who looks at everything from a business point of view. And he began comforting me with the reflection that everybody must die some day, remarking how conveniently near the cemetery I was…and hoping that undertakers did not charge very high, as he had come to the end of his last remittance.”[5] The letter reveals the rich vein of wit and humour which ran in all the brothers. Regarding Benoy Bhusan Sri Aurobindo once remarked, “He is a very nice man, and one can easily get on with him. I got on very well with my eldest brother.”

Manmohan was of a different type. He was anything but practical. He was a dreamer and a visionary. A classmate of Laurence Binyon and a friend of Oscar Wilde, he was himself a poet of considerable merit. He, Binyon, Phillips (Stephen Phillips) and Cripps…brought out a book (of poetry)[6] in conjunction, which was well spoken of. “I dare say, my brother stimulated me greatly to poetry.”[7] “Manmohan used to play the poet in England. He had poetical illness and used to moan out his verses in deep tones. (Once) we were passing through Cumberland. We shouted to him but he paid no heed, and came afterwards leisurely at his own pace. His poet-playing dropped after he came to India.”[8] He had decided to make England his home, but circumstances forced him to return. As a professor of English in the Presidency College, Calcutta, he earned a well-deserved reputation. His lectures on poetry used to be a treat. It is said that he created a poetical atmosphere, and that students from other colleges would some times steal into his class to breathe in that rarefied atmosphere of poetic enjoyment. One would often see him going up and down the stairs of the Presidency College, hat in hand, eyes downcast, and wearing an absorbed, unsmiling, and rather pensive look. He would not lift his eyes to see who passed by him. But once at his desk, he was a changed man. Warming up to his subject, he would weave exquisite patterns of romance and beauty, and fill the classroom with the vibrations of a naturally vocal sensibility. Nevinson writes of him in his New Spirit in India: “I found him there (in the Presidency College) teaching the grammar and occasional beauties of Tennyson’s ‘Princess’ with extreme distaste for that sugary stuff.” Some of his poems have been incorporated in a few anthologies of English verse, published in England, and George Sampson, writing about him in his book, The Concise Cambridge History of English Literature, says: “Manmohan (1867-1924) is the most remarkable of Indian poets who write in English. He was educated at Oxford, where he was the contemporary and friend of Laurence Binyon, Stephen Phillips and others who became famous in English letters. So completely did he catch the note of his place and time that a reader of his Love Songs and Elegies and Songs of Love and Death would readily take them as the work of an English poet trained in the classical tradition.”

Sarojini, the only sister, was much younger than Sri Aurobindo, and extremely devoted to him. We shall presently quote a letter from Sri Aurobindo to Sarojini, which shows how dearly he too loved her.

Barindra, the youngest brother, was born, as we have already seen, in England. But he came back with his mother and sister, when he was a mere child, and his boyhood days were passed at Deoghar where their maternal grandfather, Rishi Rajnarayan Bose, was living at that time. After their father’s death, Barindra had to pass through various experiences of struggle and hardship. In fact, his whole life can be said to have been a series of storms and upheavals, for much of which it was his own nature that was responsible. He had ambition and a spirit of adventure, generosity and courage, but he was domineering, recklessly impulsive and emotionally unstable. He played a major role and blazed a trail in the revolutionary movement of Bengal, and has left a name in the history of the movement; but he could never free himself from the tragic fate that dogged his steps up to the end of his days.

To take up the thread of the narrative. Sri Aurobindo visited Bengal in 1894 for the first time after his return from the West. He went to Rohini, which is about four miles from Deoghar. There he met his mother, his sister Sarojini, and Barindra. It was their first meeting after about fifteen years.

From Rohini, Sri Aurobindo went to Deoghar and met his maternal grandfather, Rajnarayan Bose, and other relatives, and stopped with them for a few days.

This high-souled patriarch, Rishi Rajnarayan Bose, a pioneer nationalist and religious and social reformer of Bengal, was then passing his old age in the peaceful retreat of Deoghar. Sri Aurobindo must have felt a great affinity with him. “Rajnarayan Bose”, as Bepin Chandra Pal says, — and no views carry more weight than this political stalwart’s who worked shoulder to shoulder with Sri Aurobindo for the country’s freedom — “was one of the makers of modern Bengal. He started life as a social and religious reformer. In him it was not merely the spirit of Hinduism that rose up in arms against the onslaught of European Christianity, but the whole spirit of Indian culture and manhood stood up to defend and assert itself against every form of undue influence and alien domination. While Keshub[9] was seeking to reconstruct Indian and specially Hindu social life more or less after the modern European model, Rajnarayan’s sturdy patriotism and national self-respect rebelled against the enormity, and came forward to establish the superiority of Hindu social economy to the Christian social institutions and ideals. He saw the onrush of European goods into Indian markets, and tried to stem the tide by quickening what we would now call the Swadeshi spirit, long before any one else had thought of it. It was under his inspiration that a Hindu Mela or National Exhibition was started a full quarter of a century before the Indian National Congress thought of an Indian Industrial Exhibition…. A strong conservatism, based upon a reasoned appreciation of the lofty spirituality of the ancient culture and civilisation of the country; a sensitive patriotism, born of a healthy and dignified pride of race; a deep piety expressing itself through all the varied practical relations of life — these were the characteristics of the life and thought of Rajnarayan Bose…. In his mind and life he was at once a Hindu Maharshi, a Moslem Sufi and a Christian theist of the Unitarian type… He…seemed to have worked out a synthesis in his own spiritual life between the three dominant world cultures that have come face to face in modern times… He was Aravinda’s maternal grandfather; and Aravinda owed not only his rich spiritual nature but even his very superior literary capacity to his inherited endowments from his mother’s line.”[10]

When Sarojini was staying at Bankipore for her education, Sri Aurobindo used to help her with money from time to time. He also sent money to his mother. The following letter written by him to his sister from Baroda not only reveals his tender love for her and his lively humour, but his eager longing to get away from the cramping atmosphere of Baroda to Bengal, which he loved so dearly, and whose call he must have been hearing within him. Something of his love of Bengal is reflected in his poem on Bankim Chandra, from which we reproduce the following three lines:

O plains, О hills, О rivers of sweet Bengal,

O land of love and flowers, the spring-bird’s call

And southern wind are sweet among your trees.

“My dear Saro,

I got your letter the day before yesterday. I have been trying hard to write to you for the last three weeks, but have hitherto failed. Today I am making a huge effort and hope to put the letter in the post before nightfall. As I am invigorated by three days’ leave, I almost think I shall succeed.

It will be, I fear, quite impossible to come to you again so early as the Puja, though if I only could, I should start tomorrow. Neither my affairs, nor my finances will admit of it. Indeed it was a great mistake to go at all, for it has made Baroda quite intolerable to me. There is an old story about Judas Iscariot, which suits me down to the ground. Judas, after betraying Christ, hanged himself and went to Hell where he was honoured with the hottest oven in the whole establishment. Here he must burn for ever and ever; but in his life he had done one kind act and for this they permitted him by special mercy of God to cool himself for an hour every Christmas on an iceberg in the North Pole. Now this has always seemed to me not mercy, but a peculiar refinement of cruelty. For how could Hell fail to be ten times more Hell to the poor wretch after the delicious coolness of his iceberg? I do not know for what enormous crime I have been condemned to Baroda, but my case is just parallel. Since my pleasant sojourn with you at Baidyanath (Deoghar), Baroda seems a hundred times more Baroda….”[11]

Sarojini must have greatly enjoyed such an affectionate and entertaining letter from her brother. Describing her brother, she once said: “…a very delicate face, long hair cut in the English fashion, Sejda was a very shy person.”

Sri Aurobindo used to pass many of his vacations at Baidyanath or Deoghar which, besides being an excellent health resort and a famous place of Hindu pilgrimage, is a lovely little town, half sleepy and half awake, with its delightful gardens, and its hills and rocks overlooking green fields and meadows. Pilgrims from all parts of India go there to worship the symbolic image of Shiva, carrying with them pots of pure Ganges water from long distances to pour upon the Deity.

Basanti Devi, daughter of Krishna Kumar Mitra and a cousin to Sri Aurobindo, says about him: “Auro Dada used to arrive with two or three trunks, and we always thought they must contain costly suits and other articles of luxury like scents etc. When he opened them, I would look into them and wonder. What is this? A few ordinary clothes and all the rest books and nothing but books. Does Auro Dada like to read all these? We all want to chat and enjoy ourselves in vacations; does he want to spend even this time in reading these books? But because he liked reading, it was not that he did not join us in our talks and chats and merry-making. His talk used to be full of wit and humour.”[12] Sri Aurobindo wrote a poem on Basanti on one of her birthdays.

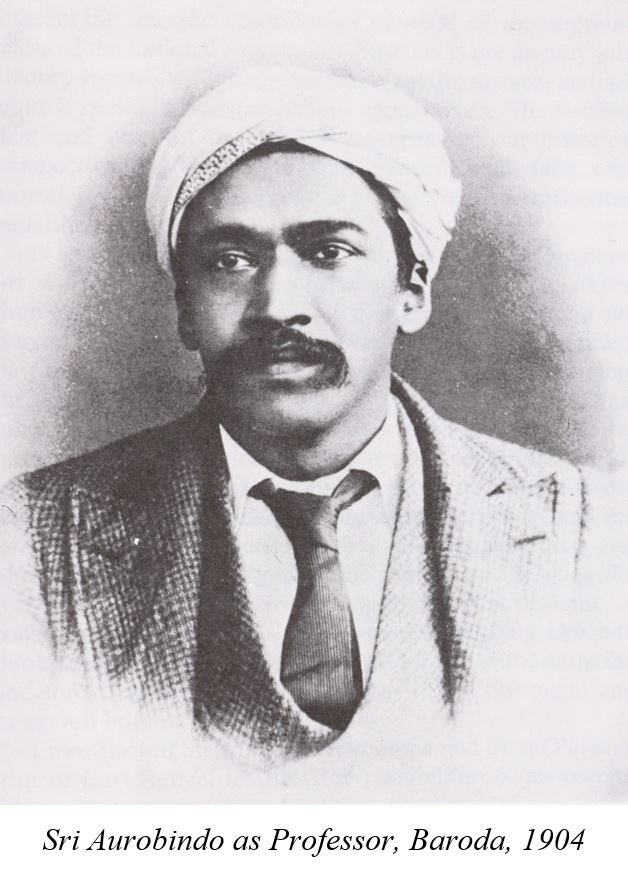

At Baroda Sri Aurobindo “was put first in the Settlement Department, not as an officer, but to learn the work, then in the Stamps and Revenue Departments; he was for some time put to work in the Secretariat for drawing up dispatches etc. Afterwards without joining the College and while doing other work, he was lecturer in French at the College, and finally at his request was appointed there as Professor of English. All through, the Maharaja used to call him whenever something had to be written which needed careful wording; he also employed him to prepare some of his public speeches and in other work of a literary or educational character.” Afterwards Sri Aurobindo became Vice-Principal of the College and was for some time its acting Principal. “Most of the personal work for the Maharaja was done in an unofficial capacity…. There was no appointment as Private Secretary. He was usually invited to breakfast with the Maharaja at the Palace and stayed on to do this work.”

Sri Aurobindo was loved and highly revered by his students[13] at Baroda College, not only for his profound knowledge of English literature and his brilliant and often original interpretations of English poetry, but for his saintly character and gentle and gracious manners. There was a magnetism in his personality, and an impalpable aura of a lofty ideal and a mighty purpose about him, which left a deep impression upon all who came in contact with him, particularly upon young hearts and unsophisticated minds. Calm and reserved, benign and benevolent, he easily became the centre of respectful attention wherever he happened to be. To be close to him was to be quieted and quickened; to listen to him was to be fired and inspired. Indeed, his presence radiated something which was at once enlivening and exalting. His power sprang from his unshakable peace, and the secret of his hold on men lay in his utter self-effacement. His greatness was like the gentle breath of spring — invisible but irresistible, it touched all that was bare and bleak around him to a splendour of renewed life and creative energy.

In regard to his work at the Baroda College, he once remarked to some of his disciples: “He (Manmohan) was very painstaking. Most of the professors don’t work so hard. I was not so conscientious as a professor. I never used to look at the notes, and sometimes my explanations did not agree with them at all…. What was surprising to me was that the students used to take down everything verbatim and mug it up. Such a thing would never have happened in England…. Once I was giving a lecture on Southey’s Life of Nelson. My lecture was not in agreement with the notes. So the students remarked that it was not at all like what was found in the notes. I replied: ‘I have not read the notes — in any case they are all rubbish!’ I could never go to the minute details. I read and left my mind to do what it could. That is why I could never become a scholar.”[14]

The testimony of one of his students, named R.N. Patkar,[15] will be found very interesting inasmuch as it throws some authentic light upon the way he lived at Baroda and did his teaching at the College:

“Sri Aurobindo was very simple in his mode of living. He was not at all fastidious in his tastes. He did not care much for food or dress, because he never attached any importance to them. He never visited the market for his clothes. At home, he dressed in plain white chaddar and dhoti, and outside invariably in white drill suits. He never slept on a soft cotton bed, as most of us do, but on a bed of coir — coconut fibres — on which was spread a Malabar grass mat which served as a bed sheet.

“Once I asked him why he used such a coarse and hard bed, to which he replied with his characteristic smile: ‘Don’t you know, my boy, that I am a Brahmachari? Our shastras enjoin that a Brahmachari should not use a soft bed.’[16]

“Another thing I observed about him was the total absence of love of money. He used to get the lump sum of three months’ pay in a bag which he emptied in a tray lying on his table. He never bothered to keep money in a safe box under lock and key. He did not keep an account of what he spent. One day I casually asked him why he was keeping his money like that. He laughed and then replied: ‘Well, it is a proof that we are living in the midst of honest and good people.’ ‘But you never keep an account which may testify to the honesty of the people around you?’, I asked him. Then with a serene face he said: ‘It is God who keeps account for me. He gives me as much as I want and keeps the rest to Himself. At any rate, He does not keep me in want, then why should I worry?’

“He used to be absorbed in reading to the extent that he was at times oblivious of the things around him. One evening the servant brought his meal and put the dishes on the table and informed him, ‘Sab, khana rakha hai’ — ‘Master, the meal is served’. He simply said, ‘Achchha’ — ‘All right’, without even moving his head. After half an hour the servant returned to remove the dishes and found to his surprise the dishes untouched on the table! He dared not disturb his master, and so quietly came to me and told me about it. I had to go to his room and remind him of the waiting meal. He gave me a smile, went to the table and finished his meal in a short time and resumed his reading.

“I had the good fortune to be his student in the Intermediate class. His method of teaching was a novel one. In the beginning, he used to give a series of introductory lectures in order to initiate the students into the subject matter of the text. After that he used to read the text, stopping where necessary to explain the meaning of difficult words and sentences. He ended by giving general lectures bearing on the various aspects of the subject matter of the text.

“But more than his college lectures, it was a treat to hear him on the platform. He used to preside occasionally over the meetings of the College Debating Society. The large, central hall of the College used to be full when he was to speak. He was not an orator but was a speaker of a very high order, and was listened to with rapt attention. Without any gesture or movements of the limbs he stood, and language flowed like a stream from his lips with natural ease and melody that kept the audience spell-bound…. Though it is more than fifty years since I heard him, I still remember his figure and the metallic ring of his melodious voice.”[17]

At Baroda, Sri Aurobindo stayed at first in a camp near the Bazar, and from there he moved to Khasirao Jadav’s house. Khasirao, who was working as a magistrate under the Baroda State, was at that time living elsewhere with his family. His house was a beautiful, two-storeyed building, situated on a main road of the town. When Khasirao was transferred back to Baroda, Sri Aurobindo had to move to a house in another locality. After some time, when plague broke out there, he had to move again to another house, which was an old bungalow with a tiled roof. It was so old and in such bad repair that it used to be unbearably hot in summer, and, during the months of the monsoon, rain water leaked through its broken tiles. But, as Dinendra Kumar Roy[18] records in his Bengali book, Aurobindo Prasanga, it made no difference to Sri Aurobindo whether he lived in a palace or a hovel. Where he really dwelt, no tiles ever burned, nor did rain water leak. He was, to use an expression of the Gita, aniketah, one who had no separate dwelling of his own in the whole world. But it was different with Dinendra Kumar. What with swarms of fleas by day and pitiless mosquitoes at night, burning tiles in summer and leaking roofs during the rains, the poor man was so disgusted that he damned the poky, ramshackle domicile as being worse than a rich man’s stable.

Among Sri Aurobindo’s friends at Baroda, mention may be made of Khasirao Jadav, Khasirao’s younger brother, Lt. Madhavrao Jadav, who was very intimate with Sri Aurobindo and helped him in many ways in his political work, and Phadke, a young, orthodox Maratha Brahmin, who was a man of letters and had translated a few Bengali novels including Bankim Chandra’s Durgesh Nandini into Marathi. Sri Aurobindo used to read Marathi with him from time to time. Phadke was of a genial temperament, cheerful and witty. Bapubhai Majumdar, a Gujarati Brahmin barrister, stayed with Sri Aurobindo for some time as his guest. He was a handsome man with an inexhaustible fund of comic stories. His laugh was contagious — it was hearty and hilarious. Sometimes his quips and jokes and droll yams would send Sri Aurobindo into bursts of laughter. He was afterwards appointed Chief Justice of a State in Gujarat.

Sri Aurobindo learnt both Marathi and Gujarati at Baroda. He also learnt a dialect of Marathi called Mori from a pundit. He had an aptitude for picking up languages with an amazing ease and rapidity. He learnt Bengali himself, and learnt it so well as to be able to read the poetry of Michael Madhusudan Dutt and the novels of Bankim Chandra Chatterji; and both of these authors are anything but easy. “Bengali was not a subject for the competitive examination for the I.C.S. It was after he had passed the competitive examination that Sri Aurobindo as a probationer who had chosen Bengal as his province began to learn Bengali. The course of study provided was a very poor one; his teacher, a retired English Judge from Bengal, was not very competent….” It is rather amusing to note that one day when Sri Aurobindo asked his teacher to explain to him a passage from Bankim Chandra Chatterji, he looked at the passage and remarked with the comic cocksureness of shallow knowledge: “But this is not Bengali!” Sri Aurobindo learnt Sanskrit himself without any help from anybody. He did not learn Sanskrit through Bengali, but direct in Sanskrit or through English. But the marvel is that he mastered it as thoroughly and entered as deeply into its spirit and genius as he had done in the case of Greek and Latin. He “never studied Hindi, but his acquaintance with Sanskrit and other Indian languages made it easy for him to pick up Hindi without any regular study and to understand it when he read Hindi books or news-papers.”

An exceptional mastery of Sanskrit at once opened to him the immense treasure-house of the Indian heritage. He read the Upanishads, the Gita, the Puranas, the two great epics, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, the poems of Bhartrihari, the dramas of Kalidasa and Bhavabhuti etc., etc. Ancient India, the ageless India of spiritual culture and unwearied creative vitality, thus revealed herself to his wondering vision, and he discovered the secret of her unparalleled greatness. His soul caught fire. In discovering the greatness of India, he discovered himself — the greatness of his own soul, and the work it had come down to accomplish. It was a pregnant moment, when his soul burst out into a sudden blaze. It was a moment of reminiscence in the Platonic sense. It was a transforming revelation. Ancient India furnished him with the clue to the building of the greater India of the future.

Sri Aurobindo translated some portions of the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, some dramas of Kalidasa, the Nitishataka of Bhartrihari, some poems of Vidyapati and Chandidas etc. into English. Once, when R. C. Dutt, the well-known civilian, came to Baroda at the invitation of the Maharaja, he somehow came to know about Sri Aurobindo’s translations and expressed his desire to see them. Sri Aurobindo showed them to him (though not without reluctance, for he was by nature shy and reticent about himself), and Dutt was so much struck by their high quality that he said to Sri Aurobindo: “If I had seen your translations of the Ramayana and the Mahabharata before, I would not have published mine.[19] I can now very well see that, by the side of your magnificent translations, mine appear as mere child’s play.”

Sri Aurobindo wrote many English poems during his stay at Baroda, and also began some which he finished later. The earliest draft of his great epic, Savitri, was begun there. His first book of poems, Songs to Myrtilla and Other Poems, was published there for private circulation. It contained many poems written in England in his teens, and five[20] written at Baroda. Urvasi, a long poem, was also written at Baroda and published for private circulation.[21] But we shall not go into any more details here about his poetical work at Baroda, for we propose to devote a whole separate chapter to his poetry, and study its growth and flowering. No biography of Sri Aurobindo can be said to be complete without an earnest attempt at a study of his poetical genius. For, as he has himself said, he was a poet first, and everything else afterwards. But he was a seer-poet, in the Vedic sense of the word, and a singer of the mystery and magnificence, the myriad worlds and wonders of creation — a mystic seer and a melodious singer of the divine Will, the divine Beauty and the divine Joy that flame and dance behind the fretful drift of our blind world.

II

“He, who is an illimitable ocean of compassion, and as graceful as a cloud-bank charged with rain; in whom Lakshmi and Saraswati revel in endless felicity; whose Face is like an immaculate lotus in full bloom; who is adored by the kings and leaders of the gods; and whose Divine Nature has been hymned in the inspired words of the Vedas — may He, my Lord, the Master of the worlds, reveal Himself to my vision.”

“A Hymn to the Supreme Lord of the Universe”

by Sri Chaitanya

In the second year of his stay at Baroda, i.e. in 1894, Sri Aurobindo had another spiritual experience, which came in the same unexpected way as the first one he had at Apollo Bunder. One day, while he was going in a horse carriage, he suddenly found himself “in danger of an accident.” But he had, at that very moment, “the vision of the Godhead surging up from within and averting the danger.” “The Godhead surging up from within” was certainly a greater and more dynamic experience than the previous one of an encompassing calm, and must have left a powerful impression upon him. In 1939 he wrote a sonnet on this experience, which we quote below from his Last Poems.

THE GODHEAD

I sat behind the dance of Danger’s hooves

In the shouting street that seemed a futurist’s whim.

And suddenly felt, exceeding Nature’s grooves,

In me, enveloping me the body of Him.

Above my head a mighty head was seen,

A face with the calm of immortality

And an omnipotent gaze that held the scene

In the vast circle of its sovereignty.

His hair was mingled with the sun and the breeze;

The world was in His heart and He was I:

I housed in me the Everlasting’s peace,

The strength of One whose substance cannot die.

The moment passed and all was as before;

Only that deathless memory I bore.

In 1902 Sister Nivedita[22] visited Baroda. “I met Sister Nivedita at Baroda when she came to give some lectures there. I went to receive her at the station and take her to the house assigned to her; I also accompanied her to an interview she had sought with the Maharaja of Baroda. She had heard of me as one who believed in strength and was a worshipper of Kali, by which she meant she had heard of me as a revolutionary. I knew her already because I had read and admired her book, ‘Kali the Mother’. It was in those days that we formed a friendship. After I had started my revolutionary work in Bengal through certain emissaries, I went there personally to see and arrange things myself. I found a number of small groups of revolutionaries that had recently sprung into existence but all scattered and acting without reference to each other. I tried to unite them under a single organisation with barrister P. Mitter as the leader of the revolution in Bengal and a council of five persons, one of them being Nivedita[23].

“I had no occasion to meet Nivedita after that until I settled in Bengal as Principal of the National College and the chief editorial writer of the Bande Mataram. By that time I had become one of the leaders of the public movement known first as extremism, then as nationalism, but this gave me no occasion to meet her except once or twice at the Congress, as my collaboration with her was solely in the secret revolutionary field. I was busy with my work and she with hers, and no occasion arose for consultation or decisions about the conduct of the revolutionary movement. Later on, I began to make time to go and see her occasionally at Baghbazar[24]”.[25]

“Then, about my relations with Sister Nivedita, they were purely in the field of politics. Spirituality or spiritual matters did not enter into them, and I do not remember anything passing between us on these subjects when I was with her. Once or twice she showed the spiritual side of her, but she was then speaking to someone else who had come to see her while I was there.

“She was one of the revolutionary leaders. She went about visiting places to come in contact with the people. She was open and frank, and talked openly of her revolutionary plans to everybody. There was no concealment about her. Whenever she used to speak on revolution, it was her very soul, her true personality, that came out…. Yoga was Yoga, but it was that sort of work that was, as it were, intended for her. Her book, ‘Kali the Mother’ is very inspiring. She went about among the Thakurs of Rajputana trying to preach revolution to them…. Her eyes showed a power of concentration and revealed a capacity for going into trance. She had got something. She took up politics as a part of Vivekananda’s work. Her book is one of the best on Vivekananda…. She was a solid worker.”[26]

Sister Nivedita tried to rope in the Maharaja of Baroda into the revolutionary movement, but the response she received from the astute ruler was rather cool and non-committal. He said he would send his reply through Sri Aurobindo, but “Sayajirao (the Maharaja) was much too cunning to plunge into such a dangerous business, and never spoke to me about it”.[27]

In 1903 Sri Aurobindo took a month’s leave and went to Bengal. His presence was required there to smooth out the differences that had arisen among some of the leading political workers. But he was soon called back by the Maharaja who wished that he should accompany him on his tour to Kashmir as his personal secretary.

In Kashmir, Sri Aurobindo had his third spiritual experience of a decisive character, as unexpected and unbidden as the first two, but of a capital importance from a certain standpoint. He says about it: “There was a realisation of the vacant Infinite[28] while walking on the ridge of the Takht-e-Suleiman in Kashmir”. In 1939, he wrote the following sonnet on this experience:

ADWAITA

I walked on the high-wayed Seat of Solomon

Where Shankaracharya’s tiny temple stands

Facing Infinity from Time’s edge, alone

On the bare ridge ending earth’s vain romance.

Around me was a formless solitude:

All had become one strange Unnamable,

An unborn sole Reality world-nude,

Topless and fathomless, for ever still.

A Silence that was Being’s only word,

The unknown beginning and the voiceless end

Abolishing all things moment-seen or heard,

On an incommunicable summit reigned,

A lonely Calm and void unchanging Peace

On the dumb crest of Nature’s mysteries.”[29]

The Kashmir tour with the Maharaja did not prove to be very happy. It was not in Sri Aurobindo’s nature to admit encroachments upon his time of study and rest, and dance attendance on the Maharaja at all hours of the day or whenever he was summoned. The Maharaja respected and admired him for his noble character, his calm and penetrating intelligence, and his brilliance, quickness and efficiency, but was often put out by his habitual lack of punctuality and regularity; and it was this lack that caused “much friction between them during the tour.”

Sri Aurobindo was Chairman of the Baroda College Union, and continued to preside over some of its debates until he left Baroda. His speeches used to be very inspiring, as we have already learnt from the record of advocate R.N. Patkar. He had also to deliver lectures at occasional functions at the palace. But so long as he was in State Service he studiously avoided introducing politics into his speeches. He used also to address the young students who had formed a Young Men’s Union (Tarun Sangha) under his inspiration.

In 1901, Sri Aurobindo went to Bengal and married Srimati Mrinalini Bose, daughter of Bhupal Chandra Bose. Principal Girish Chandra Bose of the Bangabasi College, Calcutta, had acted as the go-between. Mrinalini Devi was fourteen years old at the time, and Sri Aurobindo twenty-nine. The marriage was celebrated according to Hindu rites, and the function was attended by the great scientist, Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose, Lord Sinha, barrister Byomkesh Chakravarty etc. As Sri Aurobindo had been to England, the question of expiation was raised by the orthodox section of the community, but Sri Aurobindo refused to do any expiation, even as his stout-hearted father had refused before him. At last a face-saving proposal came from the priests that Sri Aurobindo should shave his head. But Sri Aurobindo turned down this proposal also. Then “an obliging Brahmin priest satisfied all the requirements of the Shastra for a monetary consideration!”

After his marriage Sri Aurobindo went to Deoghar, and from there, he, his wife and his sister went to Nainital, a hill resort in the Himalayas. We get a reference to this place in his letter to one Bhuvan Chakravarty, who was probably a political worker in Bengal.

Dear Bhuvan Babu,

I have been here at Nainital with my wife and sister since the 29th of May. The place is a beautiful one, but not half so cold as I expected. In fact, in daytime it is only a shade less hot than Baroda except when it has been raining. The Maharaja will probably be leaving here on the 24th, — if there has been rain at Baroda, but as he will stop at Agra,[30] Mathura[31] and Mhow,[32] he will not reach Baroda before the beginning of July. I shall probably be going separately and may also reach on the first of July. If you like, you might go there a little before and put up with Despande. I have asked Madhavrao to get my new house furnished but I don’t know what he is doing in that direction. Banerji is, I believe, in Calcutta. He came up to see me at Deoghar for a day.

Yours sincerely,

Aurobindo Ghose.[33]

Regarding his married life and relations with his wife, nothing can be more revealing than his letters to her, written in Bengali. These letters are, moreover, Sri Aurobindo’s first confession of faith, the first verbal statement of the sleepless aspiration of his soul. Here we perceive his inextinguishable thirst for God, his intense yearning to see Him,[34] and his unfaltering resolve to be a flawless instrument in His hands. We perceive that behind the surge and glow of his militant nationalism, there was the blazing fire of a spiritual aim. In the light of this secret communication to his wife, we seem to understand something of what he meant when, later, in his Uttarpara Speech, he said: “I came to Him long ago in Baroda, some years before the Swadeshi began and I was drawn into the public field”; and again when he said in the same Speech: “The Sanatana Dharma, that is Nationalism.” His fervent patriotism was but a spark of his soul’s spiritual fire. He loved Mother India with such a self-effacing ardour, because he saw the Divine Mother behind her; and love for the Divine Mother was inherent in him, suffusing and animating every fibre of his being. It was the overmastering passion of his soul. And it was this love for the Divine — in the beginning it was an imperceptible influence[35] — that made him a nationalist. Even when he found himself irresistibly drawn towards Mother India and the work of national freedom, he was secretly drawn towards God and led by His Will. His nationalism was much more than mere nationalism, it was much more than internationalism — it was spiritual universalism, if one can so put it. His Nationalism was Sanatana Dharma. It led him to toil all his life for the divine fulfilment of the whole human race, for God in man and man in God.

The goal which Sri Aurobindo held up before himself at that early age when he wrote these letters to his wife, was not escape, not Nirvana,[36] but God; not extinction of life, but its expansion and enrichment, its divine illumination, utilisation and fulfilment. Something in him intuitively revolted against the ascetic flight from life. “But I had thought that a Yoga which required me to give up the world was not for me,” he observed once. His study of the spiritual culture of ancient India had left no doubt in his mind of its “stupendous vitality”, its “inexhaustible power of life and joy of life”, its “almost unimaginable prolific creativeness”. Ancient Indian spirituality was not a despairing gospel of world-disgust and supine quiescence, whatever may have been the passing symptoms of its long period of decline. It was a virile affirmation of life, but of a life for God and in God; it was a perpetual call to divine self-expression in creative action. Sri Aurobindo’s whole being responded to this ancient call. He was a born warrior whose spiritual nerves knew no shrinking from the assaults of the world-forces. He spurned all thought of escape, for, as he has expressed it in his epic poem, Savitri, “Escape brings not the victory and the crown.” He resolved to discover the solution of the riddle of the world at the heart of the riddle itself. He laboured for God’s victory on earth, for establishing God’s Kingdom of Light in this dim vale of tears, for transforming suffering itself into the eternal bliss and blessedness of the Divine. Does not the Upanishad declare that, not sorrow and suffering, but Ananda or bliss is the eternal substratum, the sustaining sap and essence of existence? Sri Aurobindo resolved to fight for crowning the ascending spiral of evolution with the glory of the long-dreamt-of divine Manifestation.

His letters to his wife vibrate with this resolve, and contain the seed of the whole subsequent unfoldment of his life. There is another thing in them, which at once arrests attention: it is his complete, unreserved, and joyous surrender to God. The whole secret of Sri Aurobindo’s greatness lies in this integral surrender. But more of this when we come to study his spiritual life.

We offer below an English translation of some of the most important passages from Sri Aurobindo’s letters to his wife:

My dearest Mrinalini,

I have received your letter of the 24th August. I am distressed to learn that your parents have again been stricken with the same kind of bereavement; but you have not mentioned which of their sons has passed away. Grief is all too natural, but what does it avail? One who goes in search of happiness in the world finds sorrow at the core of it: sorrow is ever bound up with happiness. And this law holds good not only in regard to one’s desire for offspring, it is the inevitable result of all worldly desires. The only remedy is to offer all joy and grief with a calm mind to the Divine.

Now, let me tell you about the other matter. You must have realised by now that the person with whom your fate is linked is a very strange one. I don’t have the same kind of mental outlook, the same aim in life, the same field of action as most men have in the modern time. With me all is different, all is uncommon.[37] You know what the common run of men think of extraordinary ideas, extraordinary endeavours, and extraordinarily high aspirations. They call all that madness. But if the mad man succeeds in his field of action, instead of calling him mad, they call him a great man of genius. But how many of such men succeed? Out of a thousand, only ten may be extraordinary, and out of those ten, only one may succeed. Far from having had any success in my field of action, I have not been able to enter it. So, you may consider me a mad man. It is very unfortunate, indeed, for a woman to have her lot cast in with a mad man; for, all the hopes and desires of women are confined to the joys and sorrows of the family. A mad man cannot make his wife happy, rather he causes her no end of trouble and suffering.

The founders of the Hindu religion were aware of it. They greatly cherished and valued extraordinary character, extraordinary endeavour, and extraordinary dreams. They had a high regard for all extraordinary men, whether great or insane. But what remedy is there for the pitiable misery of the wife in such a case? The Rishis prescribed the following remedy: They said to women: Your only mantram (a formula embodying the guiding principle of life) should be that the husband alone is the supreme Guru (spiritual master) of his wife. The wife is the partner of his spiritual life. The wife should help her husband with her counsel and encouragement in all that he accepts as his Dharma or religious duty. She should regard him as her god[38] and share his joys and sorrows. It is for the husband to choose his vocation, and for the wife to aid and encourage him in it.

Now the question is: Will you tread the path of Hinduism or follow the ways of modern civilisation? That you have been married to a mad man is a consequence of some evil deed committed by you in your past life. You had better make terms with your fate. But what sort of terms? Swayed by the opinion of others, will you just airily put him down as a mad man? The mad man cannot help pursuing his path of madness, and you cannot hold him back — his nature is stronger than you. Will you, then, sit in a corner and weep your heart out? Or run along with him on his chosen road, and try to be the mad wife of a mad husband, even as the wife of the blind king (Dhritarashtra)[39] bandaged her eyes in order to share her husband’s blindness? Whatever training you may have had at a Brahmo school, you belong to a Hindu family, and the blood of our Hindu forefathers runs in your veins. I have no doubt that you will follow the latter course.

I have three manias, one might call them madness. The first is that I firmly believe that the qualities, talent, higher education and learning, and wealth God has given me, all belong to Him, and that I am entitled to use only so much of them as is necessary for the maintenance of the family, and whatever else is thought indispensable; and all that remains should be returned to God. If I used everything for myself, for my own pleasure and luxury, I should be a thief. According to the sacred books of the Hindus, he who does not render unto God what he has received from Him is a thief. Up till now, I have rendered only one-eighth to God and used for my personal pleasures the remaining seven-eighths. And, settling my accounts in this way, I have been passing my days in a state of infatuation with worldly pleasures. Half of my life has gone in vain. Even the animal is not without the gratification of feeding himself and his family.

It is clear to me now that so long I have been indulging my animal propensities, and leading the life of a thief. It has filled me with great remorse and self-contempt. No more of it. I give up this sin for good and all. To offer money to God is to spend it in sacred causes. I don’t regret having helped Sarojini and Usha with money — to help others is a virtue; to protect those who have taken refuge with you is a great virtue, indeed. But all is not done by giving only to our brothers and sisters. The whole country, in its present plight, is at my door, seeking for shelter and help. There are three hundred millions of my brethren in this land, of whom many are dying of starvation, and most, afflicted with sorrow and suffering, drag on a wretched, precarious existence. It is our duty to do good to them.

Tell me, will you, as my wife, participate with me in this Dharma? I wish to live like an ordinary man and spend on food and clothing no more than what an ordinary man of average means spends on them, and to offer the rest to God. But my wish will be fulfilled only if you agree with me and are ready for the sacrifice. You were complaining of not having made any progress. This is a path of progress I am pointing to; will you follow it?

The second mania is a recent possession. It is that, by whatever means possible, I must see God face to face. Modern religion consists in glibly mouthing God’s name at all hours, saying one’s prayers when others are looking on, and showing off how devout one is! This is not the sort of religion I want to practise. If God exists, there must be some way or other of realising His existence and meeting Him. However hard and rugged the way, I am resolved to tread it. Hinduism declares that the way lies in one’s body and mind; and it has laid down certain rules for following the way. I have begun to observe these rules, and a month’s practice has led me to realise the truth of what Hinduism teaches. I am experiencing all the signs and symptoms it speaks of. I should like to take you with me along this path. It is true, you will not be able to walk abreast of me, for you lack the knowledge necessary for it; but there is nothing to prevent you from following me. All can attain to the goal by treading this path; but it depends upon one’s will whether one should take to it or not. None can drag you along upon it. If you are willing, I shall write to you more on this subject later.

The third mania is this: Others look upon their country as a mass of matter, comprising a number of fields, plains, forests, mountains and rivers, and nothing more. I look upon it as my mother. I revere and adore it. What does a son do when he sees a demon sitting upon his mother’s chest and about to drink her life-blood? Does he sit down to his meals with a quiet mind and enjoy himself in the company of his wife and children? Or, does he run to the rescue of his mother? I know I have the power to redeem this fallen race.[40] It is not physical power — I am not going to fight with sword or gun — but the power of knowledge.[41] The prowess of the Kshatriya (warrior) is not the only power; there is another power, the fire-power of the Brahmin, which is founded in knowledge. This is not a new idea or a new feeling, I have not imbibed it from modern culture — I was born with it. It is in the marrow of my bones. It is to accomplish this mission that God has sent me to the earth.[42] The seed began to sprout when I was only fourteen, it took firm root when I was eighteen. My aunt has made you believe that some bad man has led your good-natured husband astray; but, in fact, it is your good-natured husband who has led that man and hundreds of others to the path, be it good or evil, and will yet lead thousands of others too. I don’t presume to assert that fulfilment will come during my life time, but come it will.

Well, what, then, will be your decision in this matter? The wife is the Shakti (power) of the husband. Are you going to be a disciple of Usha and practise the cult of worship of the Europeans? Will you lessen the power of your husband, or double it by your sympathy and encouragement? You may say: “What can an ordinary girl like me do in such great matters? I lack mental strength, I lack intelligence; I am afraid even to think of these things.” There is an easy solution. Take refuge in God, enter the path of God-realisation; He will soon make good the deficiencies you have. Fear gradually fades out of the person who has taken refuge in the Divine. Besides, if you put your trust in me, and listen to me instead of listening to others, I can give you out of my own power, which will increase rather than diminish by it. It is said that the wife is the Shakti (power) of the husband, which means that the husband’s power is doubled when he sees his own image and hears the resonance of his own high aspiration in his wife….

You have a natural tendency towards unselfishness and doing good to others. The only thing you lack is strength of will. It will come by turning to God with love and adoration.

This is the secret thing I wanted to tell you. Don’t breathe a word of it to anybody. Ponder over these things with a tranquil mind. There is nothing in it to be afraid of, but plenty to ponder over. In the beginning it will be enough for you to meditate on God for only half an hour every day, and to express your ardent will to Him in the form of a prayer. By and by, the mind will be prepared. Always pray to Him: “May I be of constant help to my husband in his life, his aim, and his endeavours for realising the Divine, and serve him as his instrument, and not stand in the way of his progress.”

Your husband

23, Scott’s Lane,

Calcutta,

February 17, 1907.

My dear Mrinalini,

…I was to have seen you on the 8th January, but could not, not because I was unwilling, but because God willed otherwise. I had to go where he led me. This time it was not for my own work that I went, it was for His. The state of my mind has undergone a change, but I shall not tell you anything about it in this letter. When you come here, I will tell you all I have to tell. For the moment I have to let you know only this that I am no longer my own master. Where God leads me I have to go, what He makes me do I have to do, just like a puppet.[43] It will be difficult for you to understand now what I mean, but it is necessary to inform you, otherwise my movements may give rise to grievances in you and make you suffer. Don’t think that I am neglecting you in my preoccupation with my work. Up till now I have often sinned against you, and it was but natural that you were displeased with me. But I am no longer free. You have henceforth to understand that all that I do depends not upon my will, but upon the command of God.[44] When you come here, you will be able to grasp the sense of what I say. I hope God will show you the light of His boundless Grace, even as He has shown it to me; but it all depends upon His Will. If you wish, as my wife, to share with me a common spiritual life, try your utmost to exert your will, so that He may reveal to you also the path of Grace. Don’t show this letter to anybody, because what I have communicated to you is extremely confidential. I haven’t spoken about it to anybody else; it is forbidden. No more today.[45]

Your husband

Mrinalini Devi “lived always with the family of Girish Bose, Principal of Bangabasi College”. Once, when Sri Aurobindo was at Pondicherry, his brother-in-law wrote to him, urging him to return to Bengal and lead a householder’s life. Sri Aurobindo wrote the following letter in reply.

“…You want me to live as an ordinary householder and, I suppose, practise some kind of meditation or sadhana in the time I can spare from my work and my family duties. This would have been possible if what I am called to do were an ordinary sadhana of occasional meditation which would leave the rest of my life untouched. But I wrote to you that I feel called to the spiritual life, and that means that my whole life becomes part of the sadhana. This can only be done in the proper conditions, and I do not see how it is possible in the ordinary life of the family and its surroundings. You all say that God will not bless my sadhana, and it will not succeed; but what I feel is that it is He who has called me; my whole reliance is on Him and it is solely on His Grace and Will that my success in the sadhana depends. The best way to deserve that Grace is to give myself entirely into His hands and to seek Him and Him alone. This is my feeling and my condition, and I hope you will see that this being so I cannot do what you ask for.”

Mrinalini Devi lived on in Calcutta till her death in 1918. She was fortunate enough to receive initiation from Sri Sarada Devi, the saintly wife of Sri Ramakrishna. Sri Aurobindo once remarked in this connection: “I was given to understand that she was taken there (to Sri Sarada Devi) by Sudhira Bose, Debabrata’s[46] sister. I heard of it a considerable time afterwards in Pondicherry. I was glad to know that she had found so great a spiritual refuge, but I had no hand in bringing it about.”[47]

III

“I know what is righteous, but I feel no urge towards it; I know what is unrighteous, but I do not feel inclined to desist from it. According as Thou, О Lord, seated in my heart, appointest me, so do I act.”[48]

Before we pass on to the next subject, it would be rewarding to look a little more carefully into a few statements made by Sri Aurobindo in his letters to his wife, for they not only show that he had a clear prevision of the mission of his life, but mirror the crucial stages of spiritual development through which he was sweeping during the latter part of his stay at Baroda and the beginning of his political life in Bengal. They are, as it were, a blue print of his whole life and, from that standpoint at least, most important.

First of all, he speaks of the three manias, which were the dynamic forces moulding his life and nature. The first, the will to consecrate all he was and all he had to God: “I firmly believe that the qualities, talent, higher education and learning, and money God has given me, all belong to Him.” The second, a consuming passion for realising God: “I must see God face to face.” The third, his resolve to raise India to her full divine stature for the redemption of mankind: “I look upon it (my country) as my mother. I revere and adore her.”[49] Self-consecration, God-realisation, and the service of the country as the service of the divine Mother, these three passions of his soul were really three aspects of the single mission of his life, which was a dynamic and creative union with the Divine for fulfilling His purpose on earth. But the precise nature of his mission will become more and more clear to us, as we proceed, studying the succeeding phases of his outer life and what he has himself said about them and about his thoughts and ideas in his voluminous letters and other writings.

These three master passions dominated three principal stages of Sri Aurobindo’s life. The cult of spiritual patriotism dominated the first stage; the will to total self-offering to God, the second; and divine realisation and manifestation, the third. But it must not be supposed that each of them worked by itself, during the period of its domination, to the exclusion of the others. Essentially they formed an organic unity, each helping the others, and all contributing to the accomplishment of his life’s work.

The patriotism which fired his being since his boyhood was not a mere love of the country of his birth, and a yearning for its freedom and greatness. It was worship of India, as we have already seen, as the living embodiment of the highest spiritual knowledge, and the repository of the sublimest spiritual achievements of the human race. He had no narrow partisan patriotism that attaches a person to his own country and makes him regard it as the greatest and best. He loved and adored India, because he knew that in the present Chaturyuga (a cycle of four ages: Satya, Treta, Dwapara, and Kali) India was destined to be the custodian of the supreme knowledge, and the leader of the world in the ways of the Spirit[50] — a fact which is being more and more realised and acknowledged by the master minds of the present age. He looked upon India as the spiritual battlefield of the world where the final victory over the forces of the Ignorance and darkness would be achieved. The following lines from his The Yoga and Its Objects throw a flood of light on this point and explain his spiritual nationalism:

“God always keeps for Himself a chosen country in which the higher knowledge is, through all chances and dangers, by the few or the many, continually preserved, and for the present, in this Chaturyuga at least, that country is India…. When there is the contracted movement of knowledge, the Yogins in India withdraw from the world and practise Yoga for their own liberation and delight or for the liberation of a few disciples; but when the movement of knowledge again expands and the soul of India expands with it, they come forth once more and work in the world and for the world…. It is only India that can discover the harmony, because it is only by a change — not a mere readjustment — of present nature that it can be developed, and such a change is not possible except by Yoga. The nature of man and of things is at present a discord, a harmony that has got out of tune. The whole heart and action and mind of man must be changed but from within and not from without, not by political and social institutions, not even by creeds and philosophies, but by realisation of God in ourselves and the world and a remoulding of life by that realisation.”

In the light of these words we understand something of the fiery intensity of love and devotion and prophetic ardour with which Sri Aurobindo flung himself into the national movement and the privations and hardships it entailed. He did not consider it a sacrifice at all to throw away his brilliant prospects at Baroda in order to be able to serve his country as a politician, because he believed and knew that it was really God and His approaching manifestation that he was serving. If we do not take special note of this spiritual side of his nationalism, we shall miss all the significance of his political activities and create an unbridgeable gulf between the first part of his life and the last, as has been done by many of his countrymen. If Sri Aurobindo thirsted and strove for India’s political freedom, it was because he wanted the ancient spirituality of India to triumph again, more extensively than ever before, in the world of Matter, and weave a rich, many-coloured tapestry of organic perfection for man. He knew that India was nothing without her spirituality, for her spirituality pervades her whole being, and that spirituality is not of much value, so far as our earthly existence is concerned, without its message and ministrations to life. And he knew also that India is the land of the most virile and dynamic spirituality, the land where, in the hey-day of its culture, every action of life was sought to be done as a sacrament and a living sacrifice to the Supreme. Politics offered him the first means to rouse the ancient nation into a compelling sense of its inherent spiritual potentiality and a sustained endeavour to recover its rightful place in the world. Dwelling upon the aims and bearings of his politics, Sri Aurobindo says in his The Ideal of the Karmayogin:

“A nation is building in India today before the eyes of the world so swiftly, so palpably, that all can watch the process and those who have sympathy and intuition distinguish the forces at work, the materials in use, the lines of the divine architecture…. Formerly a congeries of kindred nations with a single life and a single culture, always by the excess of fecundity engendering fresh diversities and divisions, it has never yet been able to overcome permanently the most insuperable obstacles to the organisation of a continent. The time has now come when those obstacles can be overcome. The attempt which our race has been making throughout its long history, it will now make under entirely new circumstances. A keen observer would predict its success, because the only important obstacles have been or are in process of being removed. But we go further and believe that it is sure to succeed because the freedom, unity and greatness of India have now become necessary to the world….[51] We believe that God is with us and in that faith we shall conquer. We believe that humanity needs us[52] and it is the love and service of humanity, of our country, of the race, of our religion that will purify our heart and inspire our action in the struggle.”

That Sri Aurobindo’s politics and militant nationalism were nothing but a seething focus of a world-transforming spirituality is amply attested even by his very early writings. In his The Ideal of the Katmayogin he says:

“There is a mighty law of life, a great principle of human evolution, a body of spiritual knowledge and experience of which India has always been destined to be guardian, exemplar and missionary. This is the Sanatana Dharma, the eternal religion. Under the stress of alien impacts she has largely lost hold not of the structure of that dharma, but of its living reality. For the religion of India is nothing if it is not lived. It has to be applied not only to life, but to the whole of life; its spirit has to enter into and mould our society, our politics, our literature, our science, our individual character, affections and aspiration. To understand the heart of this dharma, to experience it as a truth, to feel the high emotions to which it rises and to express and execute it in life is what we understand by Karmayoga. We believe that it is to make Yoga the ideal of human life that India rises today; by the Yoga she will get the strength to realise her freedom, unity and greatness; by the Yoga she will keep the strength to preserve it. It is a spiritual revolution we foresee and the material is only its shadow and reflex.”

In connection with the three master passions of his life, it is interesting to note that before Sri Aurobindo’s arrival at Pondicherry, where he settled and lived after his retirement from active political life (from 1910 to 1950), a famous South Indian Yogi had made a prediction that “thirty years later (agreeing with the time of my arrival) a Yogi from the North would come as a fugitive to the South and practise there an integral Yoga (Poorna Yoga), and this would be one sign of the approaching liberty of India. He gave three utterances as the mark by which this Yogi could be recognised and all these three were found in the letters to my wife….”[53]

In his first letter to his wife, written from Baroda and dated 30th August, 1905, Sri Aurobindo writes: “Hinduism declares that the way lies within one’s body and mind, and it has laid down certain rules which have to be observed for following the way. I have begun observing these rules, and a month’s practice has led me to realise the truth of what Hinduism teaches. I am already experiencing all the signs and symptoms it speaks of….” The observance of the rules laid down by Hinduism was done with such a superhuman intensity of the soul’s will and the heart’s devotion that in the course of a single month Sri Aurobindo achieved what, even in exceptional cases, takes long years of strenuous struggle to come to fruition. “I am experiencing all the signs and symptoms it speaks of….” It appears as if the floodgates of spiritual experience had been thrown open to him.

“I have the power to redeem this fallen race. It is not physical power — I am not going to fight with sword or gun — but the power of knowledge. The prowess of the Kshatriya is not the only power; there is another power, the fire-power of the Brahmin, which is founded in knowledge. This is not a new feeling, I have not imbibed it from modern culture — I was born with it. It is in the marrow of my bones. It is to accomplish this great mission that God has sent me to the earth.”

We know that Sri Aurobindo was temperamentally reserved. His answers to questions except when he was in the company of his close friends, used to be usually in the monosyllabic “yes” or “no”. His Bengali tutor, Dinendra Kumar Roy, relates that Sri Aurobindo once told him that the less one speaks about oneself the better. But in the paragraph, quoted above, he does not mince his words. We do not find in it the modesty and reticence characteristic of him in regard to personal matters.[54] Here he evidently speaks from a super-personal consciousness. Here we find the unmistakable ring of the Divine Consciousness-Force (Chit-Tapas) uttering its Will. When God speaks through the chosen soul of man, He speaks in such accents of fire. It is undeniable that, apart from the spiritual experiences he had had, there must have awakened in him something or Someone that could speak in such a prophetic tone of sovereign power. For, many can have high spiritual experiences and enjoy some kind of union and communion with the Supreme Reality, but who can speak in this categoric strain of absolute certitude, unless God speaks directly through his voice: “I know (it was a knowledge with him, not a mere aspiration or resolve) I have the power to redeem this fallen race.” He further asserts with disarming candour and forthrightness that he was born with this power, that it was bred in his bones, and that to accomplish this mission God had sent him to the earth.

“The seed began to sprout when I was only fourteen; it took firm root when I was eighteen.” When he was fourteen years old, he was in England, knowing practically nothing of India, Indian culture, or the political and economic condition of India, let alone Indian spirituality. He knew next to nothing of Yoga. The seed that he speaks of must then have been a spontaneous inner awakening, a lightning flash of his soul’s consciousness of its life-work. The seed took firm root and became stable and secure when he was eighteen. It can, therefore, be confidently stated that it was not, evidently, his practice of Yoga, which he began in 1904 (when he was about thirty-one years old), or his study of the sacred books of his country (which he began when he was twenty-two or twenty-three years old), that gave him the foreknowledge of his life’s mission. It was something he had felt and perceived growing within himself in England.[55] And it is only in the light of this mystic prescience that we can explain the sudden, unsought-for, decisive experiences and realisations that descended upon him like an avalanche ever since he set foot on the soil of his motherland. Yoga did not make him conscious of his mission, it only led him along on the way to its accomplishment. Yoga did not awaken his soul, it was his soul that spontaneously blossomed through Yoga. And that he was not only conscious of his life’s mission but of the precise nature and extent of it, is proved by his intuitive recoil from all forms of ascetic, world-shunning spirituality. When perceiving the decided bent of his mind, his Cambridge friend, K.G. Despande, advised him to practise Yoga, he flatly refused, saying that it would lure him away from the life of action. In his essays on Bankim Chandra Chatterji, the maker of modern Bengali prose and the inspired writer of the national anthem, Bandemataram, he wrote: “The clear serenity of the man showed itself in his refusal to admit asceticism among the essentials of religion.” He knew pretty well that his work would embrace all life and its activities, and that it was to the creation of a vigorous, dynamic, practical spirituality, capable of flooding all earthly existence with the treasures of the Spirit that he was called. He must have heard the dumb appeal of Matter for a restitution of its innate divinity. For, Matter, too, is Brahman, annam brahma.

Another thing that stands out in his letters to his wife is the phenomenal rapidity of his spiritual progress just after he began the practice of Yoga. Not only the signs and symptoms we have referred to and which fortified his intuitive faith in Hinduism, but a more positive result, characteristic of his integral approach to spirituality, flows at once from his self-surrender to God. “For the moment I have to let you know only this that I am no longer my own master. Where God leads me I have to go, what he makes me do I have to do, just like a puppet…. You have henceforth to understand that nothing that I do depends upon my will, but upon the command of God….” This state of being completely possessed by the Divine and moved by Him even in one’s physical action is, as Sri Aurobindo afterwards so often explained in his letters to his disciples and in his writings on Yoga, the inevitable result of an unreserved surrender of the whole being of man, including his body and all its movements, to God. But it can be achieved only after a long practice of the Integral Yoga. But, in his case, it was achieved in the course of about a couple of years. He was being led by God in all that he was doing. It can, therefore, be easily concluded that his politics, almost from the beginning of its active phase, was shaped and guided by unseen directives. It was the politics of a Yogi. And it would be irrational, for those at least who believe in unseen directives, to judge his political utterances and activities, either by the canons of current political theories and rules of expediency, or by the puny standards of unrealistic mental ethics. He did what he was led to do, in the spirit of the verse we have quoted at the head of this essay, with a joyous confidence in the wisdom of God’s guidance.

There is yet another thing that arrests attention in his letters to his wife. It is that he never thought that the final emancipation of India would come by the power of sword or gun. “It is not physical power — I am not going to fight with sword or gun —”. He wanted the political freedom of India as a step and means to the freedom and fulfilment of her soul, to a spiritual reconstruction of her thought, life and society. That can be done only by Brahma-teja, the blazing power of spiritual knowledge. He perceived that the power was in himself, he felt that it was growing in him, and he knew that it would never fail him. His politics was a prelude to his greater and wider spiritual work of raising humanity to a higher level of consciousness, which is, he knew, the immediate urge of evolutionary nature; it was not inconsistent with his spirituality. Even when he left Bengal, he left only his political field of work, but not politics. “He kept a close watch on all that was happening in the world and in India and actively intervened whenever necessary, but solely with a spiritual force and silent spiritual action.” His poetry and politics, his philosophy and Yoga were all of a piece — they composed a coherent, integrated, harmonious whole.

We shall now offer to the reader the intimate pen-picture of Sri Aurobindo by Dinendra Kumar Roy, which we have promised.[56] Dinendra Kumar was a distinguished man of letters in Bengal. He was sent by the maternal uncle of Sri Aurobindo to help him learn the Bengali language, particularly its colloquial form and pronunciation. Dinendra Kumar stayed with Sri Aurobindo in the same house for a little over two years from 1898, and had the opportunity of making a close study of his life and nature. His testimony, besides being authentic, affords glimpses of Sri Aurobindo’s private life, which we get nowhere else. Here we see how he lived from day to day, what were his habits, his tastes, his characteristic reactions to men and things, his instinctive gestures and chance utterances, his views on some of his well-known contemporaries etc. — little details and sudden flashes which, according to Vivekananda, reveal the greatness of a great man more than his deliberate thoughts and public actions. We are giving below an English version of some portions of Dinendra Kumar’s Bengali book, Aurobindo Prasanga.

“My beloved friend, late Suresh Chandra Samajpati,[57] once told me: ‘When Aurobindo was at Baroda very few Bengalis knew him or recognised his worth. Nobody was aware of the treasure that lay hidden in the desert of Gujarat…. But during his long stay there, you were the only Bengali who was fortunate enough to have the opportunity of knowing him intimately and observing him at close quarters for some time…. Today new Bengal is eager to hear about him….” Today millions of Bengali readers are, indeed, very anxious to know something of the past life of Aurobindo. I hope the holy saga of the life of this dedicated servant of Mother India will not be disregarded by the youth of Bengal.

“What little I know of him is derived from my personal experience. When I was asked to coach Aurobindo in Bengali, I felt rather nervous. Aurobindo was a profound scholar. He had secured record marks in Latin and Greek in his I.C.S. examination. He had received heaps of books as prizes from the London University. Among those books, there was an exquisite illustrated edition of the Arabian Nights… in sixteen volumes, which I later saw in his study. I had never seen such a voluminous edition of that book — it dwarfed even the Mahabharata in bulk, looking, as it did, like sixteen volumes of the Webster’s Dictionary. It had innumerable pictures in it….