I

Last year, I wrote two articles describing my connection with Sri Aurobindo in the field of secret political work. He approved of both the writings and they were duly published in two special numbers of the Amrita Bazar Patrika. There were, however, many things of a more or less intimate nature which, out of delicacy, I kept back at the time. Many of my friends have, of late, been pressing me to write about them. Still, I have hesitated for several months. Since the passing away of the Master, strange tales about his earlier life have been sprouting out, like mushrooms, all around us. The phenomenon is natural enough after a long period of reticence and it can do harm, for Sri Aurobindo is above human appraisement. But in this atmosphere, I feel very shy about unpacking my bundle of rags, invaluable though they are to me. If he had but once glanced at them, they would have turned to priceless shawl and brocade. Still he is my all, and, wherever he may be, I am sure he would protect me and guide me. I look for no protection against censure, for censure is to me a laurel crown; it is guidance I need as to what can be said and how. In the matter of very intimate experiences, human language is an inadequate medium of expression. My readers have probably heard of the great mystic of Sindh, Shah Latif. He has told a story, something like this, bearing on the point: One day, I was sitting by the village well meditating on my beloved. (The Sufi loves to call God his beloved, his M’ashuqa). The women of the village were coming and going with their pots. Suddenly I saw three very pretty girls, approaching the well. As they passed by me laughing merrily, I heard them speaking of the delirious joy they had felt in their husbands’ company the night before. One of them, the youngest, was shy and spoke very little. The other two chafed her and said, “What, little one, you did not experience any joy!” “Joy!” was the reply, “Yes, sister, very great joy. But how can I describe it in words!” They passed along. I closed my eyes and said to my beloved, “Truly, M’ashuqa, can that bliss be described!”

Do I not know the ecstasy of union with my Master? Of course I do, but without his Grace I cannot convey it to others. Well, I lay my difficulty at his feet, let him solve it as he will. I never hesitate to tell him anything. Face to face with him, all sense of awe and fear, of shyness and shame vanishes into thin air — a soft sweet rosy light of love pervades me. But am I so unfortunate as not to know that my Aurobindo is also the Lord of all — and the Supreme transcending all? No, I certainly know him to be all this, but my direct perception, my intimate contact is of the Lord of my heart. If he leads me to realise His other aspects, I shall realise them. When on the 5th of December last, at early dawn, I saw him in his last sleep, tears gushed out of my eyes and I said almost audibly, “I shall never see that sweet face again!” I wept then for my friend, comrade and master of yore who had passed away — not for the Lord of the Universe who is deathless. Thereafter he consoled me and I wept no more. But a void remained in the heart, a hidden grief that something that was is no more. But it is equally true that He is ever present within me, present more intensely than he had been before.

Do I not know the ecstasy of union with my Master? Of course I do, but without his Grace I cannot convey it to others. Well, I lay my difficulty at his feet, let him solve it as he will. I never hesitate to tell him anything. Face to face with him, all sense of awe and fear, of shyness and shame vanishes into thin air — a soft sweet rosy light of love pervades me. But am I so unfortunate as not to know that my Aurobindo is also the Lord of all — and the Supreme transcending all? No, I certainly know him to be all this, but my direct perception, my intimate contact is of the Lord of my heart. If he leads me to realise His other aspects, I shall realise them. When on the 5th of December last, at early dawn, I saw him in his last sleep, tears gushed out of my eyes and I said almost audibly, “I shall never see that sweet face again!” I wept then for my friend, comrade and master of yore who had passed away — not for the Lord of the Universe who is deathless. Thereafter he consoled me and I wept no more. But a void remained in the heart, a hidden grief that something that was is no more. But it is equally true that He is ever present within me, present more intensely than he had been before.

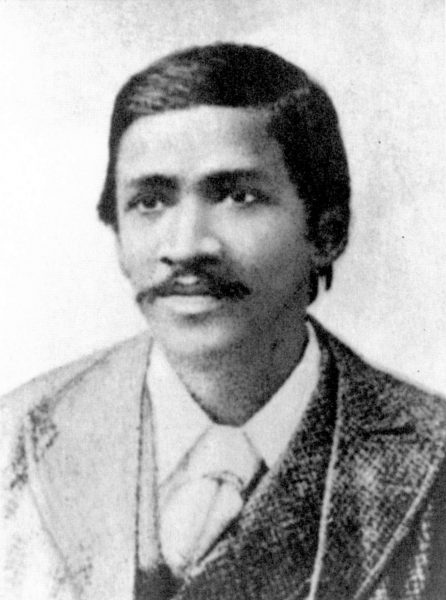

In the remote past, when I was a school-boy, Benoy, the eldest brother of Aurobindo, came to live in our little town. He used to regale us with interesting stories of many lands, and spoke often of his favourite brother, Auro, of his sweet temper and brilliant genius, of the fond love that their father bore him. But along with all this lavish praise he would always refer to his brother’s stubborn nature — “But, my Jove! he was obstinate as a mule!” Now, we are all familiar with the old portrait of Sri Aurobindo as a boy of eleven. His brilliant intelligence and sweet temper are apparent enough therein, but there is nothing to indicate that he was “obstinate as a mule”. In his actual life, however, we have had many instances of an unbending nature, that is to say, of firm determination rather than of stubbornness. His famous letters to his wife amply indicate this firmness, along with a loving and affectionate nature. His failure to appear at the riding test in England was no idle whim. As he explained to me one day, it was the least unpleasant way of letting his father know that he did not want to join the I.C.S. I always looked upon Aurobindo as a resolute man, — a man who knew his mind. As my revolutionary chief he was never whimsical or capricious. But his outstanding quality was an infinite compassion, his justice was ever tempered by mercy. I am speaking, just now, of the period before his final departure from Calcutta, when he acted principally under the guidance of his rational intelligence. Once in 1907, a report came to him that a certain young revolutionary worker had been guilty of grave misconduct. I was then in Calcutta. Ordinarily, in such cases, we took the necessary action and informed him of it. But he took up this particular case himself and ordered a very severe punishment. When he told me of it, I assured him that his order would be carried out without delay. My difficulty was that I was not myself convinced of the young fellow’s guilt. But it was not for me to reason why, when I received an order. So I issued the necessary directions. Next morning, I found him sitting listlessly with a sad look on his face and asked, “You are quite well, Chief?” He replied, “I don’t feel comfortable about that matter of yesterday. Have I been hasty? You never said anything, Charu!” “Dо I ever say anything when you issue an order?” I got up promptly and walked out saying, “Let me see how far things have gone. If at all possible, I shall stay execution of your order.” Luckily it was not too late and the previous order was countermanded. His mercy stepped in to temper the severity of his justice. Those who have had the good fortune of attending on the Master personally here in the Ashram, have had daily experience of his sweet temper and his beautiful smile. But we others, we have seen instances, too, where a sadhak, gone astray, was recklessly proceeding to dig his own grave, while the Master was trying persistently to save him. The Lord of the sinful, the Lord of the destitute, the Lord of the weak, has ever been like this!

When in 1890 I came to Calcutta for my studies, I used to hear a great deal about Aurobindo Ghose. Whatever we heard astonished us greatly. The son of a rabidly Europeanised man like Dr. K.D. Ghose, a boy brought up in England from early boyhood, has so thoroughly Indianised himself in his dress and food and habits that people can never cease talking of it. And when he married, he chose a very young Bengali bride and went through the whole of the old-fashioned Hindu rites! People told us that he was a man vastly learned in Western lore and was now engaged diligently in learning Sanskrit and various modern Indian languages. Young as we were, we could not quite tally things. But we said often to ourselves that Bhupal Babu’s little girl, Minu, was indeed a lucky wife. Her clever husband was bound to be the Diwan of Baroda one day. I had always been very anxious to have a glimpse of this prodigy, but had no luck. In 1896, I went away to Europe for a few years, and it was not till my return home that I met him casually on the Baroda station platform, as I have already stated elsewhere.

In the seventies of the last century, when the famous Keshub Chandra Sen had gone to England, he had created a sensation, and the Punch wrote of him: “Who is this Keshub Chandra Sen? Bigger than a bull, smaller than a wren, is this Keshub Chandra Sen?” Twenty years later, much the same question passed and repassed in the Indian mind with regard to Aurobindo Ghose. Who and what is this wonderful young man? Is he going to be somebody truly great or is he going to drop and wither like so many others?

And what did his English fellow-students think of him? A couple of very short stories would give my readers some indication of this. In the second year of my service, (I had not met Aurobindo as yet,) I had a boss of the name of Percy Mead. He was a very nice fellow, only a little older than myself. Once, while we were camping not far from each other, he asked me to go over to his camp the next day, saying, “There are some important matters pending, which we can fix up when we meet. Then we shall have a short walk, a simple meal and a long chat. In the morning I shall ride with you a part of the way to your camp.” I rode up, accordingly, to Mead’s camp the next day, arriving at about 4 p.m. The work took us about an hour to finish. After that we rambled in the fields till dusk. After a quick dinner we chatted for a couple of hours on a variety of things, big and small, and got into bed about midnight. In a little while, Mead called out, “Dutt, are you a Bengali?” I said, “I am, but why do you ask?” He replied, “There was an Indian student in my days, at the ‘Varsity, a great classical scholar, who had well-nigh beaten all record in Latin and Greek. His name was Aurobindo Akroyd Ghose. I knew him well. In fact, he helped me materially in my studies. Do you know him? I have an idea that he was a Bengali, though some fellows, because of his English middle name, said he was a Christian.” I laughed, “No, he is not a Christian, he is a Hindu Bengali. I know his people, but I have not actually met him as yet. He is the vice-principal of the Baroda college.” Mead said, “It is a pity that the man is an Indian and has had to come to this country. He would have been a famous professor in Cambridge. Well, Dutt, remember me to him when you meet him and tell him Percy Mead of Cambridge was inquiring after him. Good night”! A couple of years later, I recounted the tale to Aurobindo. He replied promptly, “Yes, I remember young Mead. He was a nice fellow, not stuck up like the average public school man.”

Another English civilian, once a fellow-student of Aurobindo, made a funny remark to me, some years later: “Fancy, Ghose a ragged revolutionary! He can with far greater ease write a big lexicon or compose a noble epic.” I have forgotten the man’s name, but he had a great regard for his fellow-student of the old days. I wonder if he is still alive and has read “Savitri”. Truth to tell, no one understood my chief, not even his clever Maharaja. In 1907, when I met His Highness in Baroda, he said to me quite solemnly, “Try and persuade your friend not to resign from his job here. Let him go on extending his leave. Otherwise they are sure to lock him up.” When I told Aurobindo this, he laughed out, “The old man will never understand my politics. Still, he is fond of me, I suppose. Of course, you would say it is the fondness of the Moslem housewife for the fowl that she is fattening up for the festive meal.” But I was always sure that I understood his politics. I had a fear all along that he would suddenly leave us, one day, to go up to a higher plane. Well, has he not done so more than once? From Baroda to Calcutta, from Calcutta to Pondicherry, from Pondicherry to another world, as soon as he received the call from within, or from above! As long as I did not realise that he was the embodied Divine, I tried to appraise his actions by my intellect. That he was always a Yogi, a Seeker, I never doubted. Towards the end of his Baroda days, he initiated Deshpande and Madhavrao in the Omkar Mantra, and they practised it assiduously. What he did, or tried to do, all along, for an absolute duffer like me, I am going to relate presently. When the time truly came for me to enter the spiritual path, he took a decisive step. His compassion towards me was boundless. He had gone on preparing me by a series of very subtle steps, before he finally threw wide open the portals of my heart. All this I shall recount, as I go on.

In 1910, at the end of my compulsory furlough, I rejoined my job in Sindh. The chief left Calcutta the same year and took up a new line of work here in Pondicherry. All this I have related already. In 1925, I retired from service and took up residence in Bengal. For some time I had to encounter very stormy and inclement weather, and my wife used to tell me constantly, “Go and see Ghose Saheb; he will give you peace.” But I could not get over my huff as yet; I could not forget how he had deserted us, at a critical time. I worked for Rabindranath for about seven years. I took up literary work. I dabbled in art. But nothing brought me peace. Probably association with the great poet somewhat broadened my narrow and blood-thirsty patriotism. I was, however, nothing to speak of. Occasionally some letters of Sri Aurobindo came to my hand; I read them eagerly, but without much understanding. About this time, a young sadhak of the Pondicherry Ashram wrote a very kind letter to me, somewhat in this strain, “There are many of us here, who are very keen on meeting you. Won’t you pay us a short visit?” However much of a rationalist I might have been, I believed that these people were in quest of something sublime and, what is more, they had, in their Master, the greatest spiritual personality of the age. Still, I did not respond to the cordial invitation of this young Yogi. I wrote to him, “I shall not go to your Ashram to satisfy my curiosity. When I go, it will be to offer myself.” Idle words! For, today, I know whose loving hand was invisibly pulling the strings the whole time, unfit though I was for a spiritual life.

At this time, I was fully occupied in writing on a variety of subjects — physical sciences for the young, a biography of Shivaji for the University, a history of the national movement for the Congress, novels and short stories for the general reader and a number of reviews for periodicals. Strangely enough, it was a writing of this last class that changed the whole tenor of my life. It was like this. I wrote a very long review of Jawaharlal’s Autobiography in the Viswa-Bharati quarterly, which attracted some notice, at least of people who knew me. A sadhak of the Pondicherry Ashram sent this review up to Sri Aurobindo with certain words of hyperbolic praise about myself and asked this question, “Did you, Guru, have any contact with this gentleman of yore? Political?” The reply of the Master came down promptly, “Charu Dutt? Yes, saw very little of him, for physically our ways lay far apart, but that little was very intimate, one of the band of men I used most to appreciate and felt as if they had been my friends, comrades and fellow-warriors in the battle of the ages and would be so for ages more. But curiously enough, my physical contact with men of his type, there were two or three others, was always brief. Because I had something else to do this time, I suppose.”

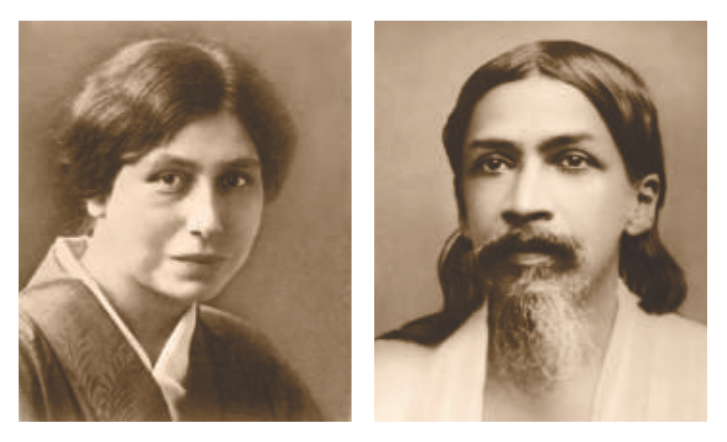

The young sadhak sent this reply to me at Calcutta. On seeing it I was overwhelmed by a sense of shame and sorrow. I sat stupefied for a while. Then my wife said, “I have told you so often before. Go to him for a while, he will give you peace”. I wrote immediately to my Pondicherry friend, “The time has come for my pilgrimage to your Ashram. Please take Sri Aurobindo’s permission and make necessary arrangements.” What wonderful Grace! Here I am, an insignificant person; for thirty whole years I have, through a stupid huff, kept away from Him and spoken irreverently of Him, at least in my thoughts, and He, the great Soul, has been, unknown to me, drawing me, gently but persistently to His feet, once again. The reply from Pondicherry came promptly. Sri Aurobindo has permitted me to be present at the next February Darshan. Not only has he accorded his gracious permission, but has cracked a homely joke at my expense — “Does he still smoke that old pipe of his? If so, how can he live in the Ashram?” I was then, in a very happy mood. I replied, “Tell Sri Aurobindo that my pipe is my servant; I am its master”. Thus far it was easy enough; but I was a stranger to the Mother of the Ashram! So much had I heard about her, both from devotees and her detractors! I had paid no heed to things that people said of her. It was easy enough to see that she was a remarkable and powerful personality. I had in the past come into contact with great European women like Mrs. Besant and Sister Nivedita, but there never was any question there of my prostrating myself before them, they were not Divine personalities! However, these things had not passed through my mind before I was actually face to face with Mother in Pondicherry. When the difficulty arose, the Master himself in his infinite Mercy, solved it for me. Otherwise my Yoga would have ended even at its commencement. It is best that I should own up to what happened. In these days, there used to be a general blessing by the Mother, on the eve of the Darshan. Along with others, I filed into the meditation hall escorted by a kind friend. At the very last moment, the thought passed through my mind, — “If I do not feel inclined to touch the feet of this European lady what then?” I decided immediately that I would not play the hypocrite. If I did not feel disposed to touch the Mother’s feet, I would just do an ordinary namaskar by raising my joined hands to the forehead, and then, immediately on returning to my quarters, I would write a letter to her — “Revered Mother, unable to fall in with the Ashram discipline, I am leaving Pondicherry forthwith.” The Master saved me from this dire disaster. As soon as I glimpsed the Mother’s radiant feet, I cried to myself “Fool, fool! You thought these were human feet!” and rushed forward to seize them. A powerful current passed through my frame, and the problem of the Mother’s personality was solved for ever. On the morrow of the Darshan, Nirodbaran, the Master’s constant attendant, asked me, “What happened, Sir? Why did the Master say, — ‘So, Charu Dutt did bow down before the Mother!’” I explained, in all pride, to the friends present, how the Master had saved me.

[Reprinted from “Sri Aurobindo Circle”, Eighth Number, 1952]