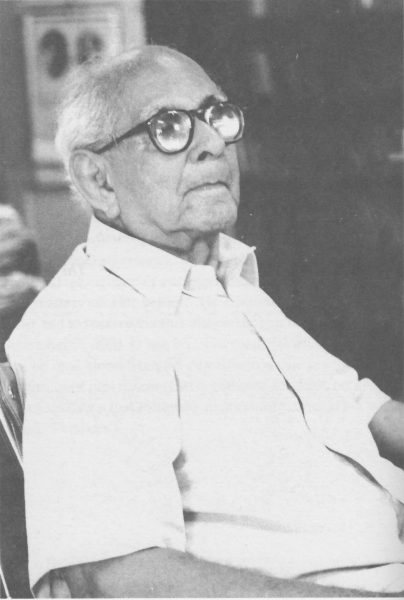

Amal now calls home the Ashram Nursing Home on Goubert Avenue where he has resided since May 1999 after his hip was broken. He does not want to return to his house as he is well taken care of at the nursing facility and is freed from all the responsibilities of “housekeeping”, as he says. The monsoon rains were teeming on many days that I visited him, but there was always sunshine when I entered his room because of his warm, welcoming and sunny disposition. This was true, also, of his lovely assistant, Minna Paladino. He is given daily physical therapy sessions, receives many visitors and when I arrived he was often sitting in the sun room overlooking the Bay of Bengal, pondering the tireless waves and surf that pound the concrete walls along the boulevard. He seemed quite peaceful and contented.

Amal was born Kekushru (Kekoo) D. Sethna on November 25, 1904 in Bombay. The family were members of the Parsi community in Bombay; descendants of the Zoroastrian Persians who fled their homeland to India in the 7th and 8th centuries to escape Muslim persecution. His father was a prominent doctor in Bombay and the family adhered to the traditional Zoroastrian faith. Young Kekoo passed through a phase of religious fervor in his childhood and prayed daily from the Zoroastrian Book of Prayers called Avesta, in the ancient Persian language of Avestan. When he was afflicted with polio at the age of around 2 years, his father took him to London for surgery to correct the paralysis. The surgery was somewhat successful but a slight limp remained. This, however, obviously did not stand in the way of his many lifetime achievements. I asked him what were some of his childhood ambitions and he said that at one point in his youth he wanted to be just like Sherlock Holmes because he “admired his mysterious and probing mind, his quick intelligence and high brow”. He used to ask the barber to cut his hair so that he would look just like Sherlock Holmes!

Soon young Kekoo was writing verse and novelettes and binding the books himself. As he grew into his teen years he began to doubt the existence of God and began to probe scientific literature. He was soon reading Joseph McCabe, an exponent of the German Haeckel’s Science of Materialism. His father was incensed about this and told Kekoo that Haeckel was an atheist and that he did not want the “wrath of the Almighty brought down upon his house.” The young boy replied, “the wrath will come if the Almighty comes!” His father said, “I will call upon all the learned of the community to come and reason with you.” The son replied, “I look forward to talking to them.” (The great thinker was being “hatched”.) Amal said that he never would have dreamt that after his father’s death (which came not long after this period) he would eventually take up the spiritual life at the Sri Aurobindo Ashram. (He became a brilliant student of literature and philosophy at St. Xavier’s College in Bombay and was studying for his MA when he arrived at the Ashram in 1927. He gave up all formal education after joining the Ashram.)

The interest in the science of materialism with its theories and debates regarding free will vs. predestination, continued for a time but would soon change. A new way of thinking was on the horizon. His girlfriend, at that time, spoke to him of a Bengali yogi and devotee of Sri Krishna who visited Bombay periodically. His name was Pagal (“mad for Krishna”) Hamath. They went to see him.

Amal put a question. “I believe that the universe is ruled by fixed laws. Where, then, does God come in?” The yogi replied, “If there are laws then there must be a lawgiver”! Amal thought he was being verbally tricked but sensed something in his tone that led him to believe that it was an answer beyond the intellect. This was the first time that his intellectual interrogation was squelched. A sense of something deeper was expressing itself, something of intuitive knowledge, so he could not bring himself to engage in mental questioning. This event led him to begin reading Vivekananda and Sri Ramakrishna. In this period he went to another yogi, Yogi Devji, who taught him some breathing exercises. The yogi went about the room touching people on the top of the head and Amal felt a powerful electrical current down his spine. He had people render themselves immobile and draw the whole of their being upward from the feet through the top of the head where he said there would be “spiritual presences in the room ready to help them”. Amal tried to do this and suddenly found himself in an out-of-body experience in quite a conscious way. He knew he wasn’t dreaming. He was watching himself do this extraordinary thing; then he asked a self-conscious question, “How is this possible?” With this question there was a sudden rush back into the body. He said that with this he learned not by any argument, but by actual experience that we are more than just a body. This, finally, was the proof for him that he wasn’t just a physical form and no materialist thinking could convince him otherwise. From this point onwards his entire outlook on reality changed.

How He Came to Sri Aurobindo

One day he went to the Crawford Market in Bombay to buy a pair of shoes. Upon his return home he took notice of the newspaper in which the shoes were wrapped. He opened up the paper and there before him was an article entitled “A Visit with Aurobindo Ghose”. He avidly read the article and said, “this is the kind of yoga I’d like to do…under a master yogi like Sri Aurobindo who can read in six different languages and appear in more than one place at a time!” He did not think it odd that a yogi could appear in more than one place at a time, but a yogi who could master so many languages, including Greek and Latin, was a remarkable phenomenon to him. He wrote to the Ashram and received a reply from Sri A.B. Purani saying that he and his girlfriend could come there and “try it out”. Before leaving, he satisfied his grandfather, now the family patriarch, and married his Parsi girlfriend. This was a good decision as, traditionally, newly married couples in India receive sizeable sums of money from family and friends, so now he had sufficient funds to travel to Pondicherry. This was 1927 and he was twenty-three years old. After some time in Pondicherry he sent a telegram to his grandfather that read “Enjoying picturesque Pondicherry”! After they had been there for nine months his grandfather wrote back “Where is the baby?” The reply was that they had had a new inner birth and that was the “baby”! He and his wife Lalita, who had accepted Sri Aurobindo and the Mother, eventually lived separately and she stayed on in the Ashram for almost 10 years before returning to Bombay. Amal Kiran (“A clear ray”) was given his name by Sri Aurobindo in 1930. Amal’s poetic genius was recognized and nurtured under the guidance and inspiration of Sri Aurobindo and he ultimately entered into correspondence with Sri Aurobindo on Savitri. After Lalita left, Sri Aurobindo warned Amal against any serious affairs with women. However, there was a young Parsi woman in Bombay, Sehra, who had loved him years before and had never married. When he returned to Bombay on a visit they were reunited and married. He told her he would give her ten years of married life and then he would return to Pondicherry. Mother India was launched in 1949 and he continued to edit the magazine from Bombay. He and Sehra eventually returned to the Ashram on February 12, 1954 and Sehra passed away on April 24, 1980.

Following are some of the questions I put to Amal and his answers:

Would you describe your first darshan with Sri Aurobindo and the Mother? What experiences did you have with them?

The first darshan with the Mother I had the impression of a radiance all around her. When I first saw Sri Aurobindo I had the sense of something leonine, as well as a mountainous calm. He leaned forward and blessed me with both hands about my head. The Mother kept smiling all the time as if to set me at ease in the presence of Sri Aurobindo. My turn to go to them was to follow an American couple that I overheard discussing whom to bow to first. They solved the problem by bowing between them. This way they touched the feet of neither but had the rare experience of being blessed by both of them at the same time. I looked at Sri Aurobindo and saw him gently moving his head forward and backward with an expression on his face as if he saw my inmost being. I felt afterwards a little disappointed with myself for having examined his look and general appearance. I liked the shape of his nose and the way he seemed to look deep within me. But afterwards. I did feel disappointed with myself for having concentrated on his outer appearance. When I met the Mother later on I asked her, “Mother, has Sri Aurobindo said anything about me?” She said, “Yes, he told me that this young man has a good face.” So it seemed to be “tit for tat”. I was a little disappointed but I told myself that to have a good face in Sri Aurobindo’s eyes cannot but mean a great deal — at least it meant that I could face the difficulties of the yogic life. Sri Aurobindo had a soft, very soft voice, I am told, but I never heard him speak.

Can you describe the atmosphere of the Ashram when Mother and Sri Aurobindo were in their physical bodies and the difference since that time?

The general atmosphere of the Ashram did not change radically. When both Sri Aurobindo and the Mother had left their bodies, I could still feel their presence. Perhaps because their subtle physical was said to have extended a number of miles beyond their bodies. I remember being told that their subtle physical auras extended up to the Lake Estate, several miles away. So it may be said that they hold us close to them even at a great distance.

In what way did your sadhana change after they left their bodies? How has the sadhana changed for you at this stage in life and what new forms has it taken?

The sadhana has not fundamentally changed since my first experience which was the opening of the heart center about six months or so after I settled in Pondicherry. I was persistently wanting this opening of the heart and several times I made the Mother touch me with her hand in the middle of my chest asking her to break me open there and at last there was an opening. At that time, I realized just how shut human beings are in their heart region. With that opening came the sense not only of a great wideness but also of a lovely atmosphere full of flowers and fragrances accompanying this happy warmth. Sometimes the sense of the opening was so intense that I felt almost breathless and prayed that this heavenly feeling would never go away.

What changes do you see taking place in the Ashram in the future and will it be different, in any way, from what it is now?

So long as a nucleus of sadhaks exists in the Ashram who are really doing the yoga, the Ashram will remain as it always has been.

What do you see as being the strongest attributes and contributions of Americans to the work of Mother and Sri Aurobindo?

Mother felt that external help for the growth of the Ashram would come imminently from America, but she said there would be a sort of tantalizing connection. I remember her saying that Ganesh, the Lord of Wealth, would always help her but often in a wayward way. There were times when the Ashram was almost desperately in need of money. The Mother had to sell her own saris to obtain the needed relief. There were some American followers who bought the saris and then offered them back to the Mother. A great deal of money began to pour in to the Ashram from America after the Mother’s departure.

I always felt a special admiration for those who had never seen Mother or Sri Aurobindo in their physical bodies and yet could dedicate themselves to the Ashram life… especially those people from America and other countries. I know of some who had come here as fulfilling a part of their pilgrimage in India but having been here for some time dropped their idea of seeking elsewhere and stayed on in the Ashram. The first Americans to settle here were a couple named Mr. and Mrs. McPheeters. The husband went out to travel to various places and when he returned was not quite the same person. During his absence his wife became part of the small group that used to meet the Mother in the prosperity store room before the soup ceremony took place. Janet McPheeters would have stayed on if it had not been for her husband who wished to return to America.

One difficulty occurring in the sadhana is straying from the path, doing what one knows not to do, becoming discouraged, etc. Did this happen in your sadhana? How to guard against this happening and what to do if and when it comes?

Straying from the path and doing what one knows not to do are real obstacles in yoga. Becoming discouraged now and again is a very common phase but one can get over this condition by appealing again and again to the Divine for help. In any kind of difficulty the most powerful help lies in praying to the Divine to carry one safely through the dark periods. The Divine is always ready to pick you up whenever you fall. A certain passage in the Mother’s Prayers and Meditations has been the chief support of my yoga. It begins, “O Divine and adorable Mother, what is there that cannot be overcome with Thy Help?” There is also the passage, “Thou hast promised to lead us all to our supreme destiny.” Not always to go on struggling but to appeal to the Mother to take up our struggle is one of the major secrets of success. Perhaps it is best summed up in the formula “Remember and Offer”. To practice this most fruitfully one must stand back inwardly from the invading impressions.

Now that you are in your nineties, what has yoga done for you at this stage in your life?

My paramount aspiration, as stated earlier, was to have the opening in the heart — what Sri Aurobindo called the Psychic Being. This gave me an intense feeling of joy that was self-existent. I was always afraid it would not last, but last it did, though not always at the same pitch. Ever since this first breakthrough there has always been a sense of a radiant response to the presence of the Mother and Sri Aurobindo.

Could you explain what it was like to be Sri Aurobindo’s correspondent for Savitri?

A friend of mine with some literary accomplishment gave, on my invitation, his comments on Savitri. Mostly they were critical. I submitted them to Sri Aurobindo and he considered them by answering. He found them not sufficiently penetrating because the writer had no spiritual background, but as they were from an accomplished literary consciousness, Sri Aurobindo thought it worthwhile to enter into a discussion with him. When I sent a copy of Sri Aurobindo’s answer to my friend he was rather apologetic and said that if he had known that Sri Aurobindo would read them, he would have been less “downright” in his tone. It was good that he was “downright” because thereby he gave Sri Aurobindo an opportunity to reply at length. Sri Aurobindo considered his comments as representative of a competent critical mind and he wanted this kind of mind to realize the newness of such poetry as Savitri, which was written from a yogic consciousness. Sri Aurobindo’s answers to various criticisms by me helped to make clear the level from which Sri Aurobindo wrote his spiritual poetry. Sri Aurobindo said my questions to him were based on some understanding of the kind of poetry he wrote and the plane from which He did so. Whereas, my friend’s comments were lacking in sympathetic understanding. Savitri struck me as opening up an entirely new world not only of experiences but of literary expression. It was a great help to me because I was eager to write from what Sri Aurobindo called the overhead planes. Of course I aspired to participate in that consciousness but more directly my aim was to open myself to the influence and receive the direct utterance of poetry. It was possible to be receptive to it without myself getting stationed on those higher levels. Sri Aurobindo distinguished these levels as higher mind, illumined mind, intuitive mind and overmind intuition. He considered these planes as being communicated by us through our poems. The sheer overmind was difficult to tap and examples of the sheer communication could be found mostly in the Rig Veda, Upanishads and part of the Gita. It was interesting to realize that by silencing one’s mind and keeping the consciousness looking upward, as it were, it was possible to write the highest spiritual poetry now and again without being stationed on those overhead levels. It is also interesting to note that one or two skillful changes in a poetic statement could mean a leap from the mental level to the overhead one. A striking example can be given by the small change made in one line like:

“A cry to clasp in all the one God-hush”

A sheer uplifting of the plane can come by transferring two words from the middle of the line to its end so that the line would read:

“A cry to clasp the one God-hush in all”

The first version suggests that this cry could be suggested by an effort to catch it while the other version transmits the plane directly.

For many years you had been going to the samadhi for long meditations on a daily basis. Would you describe what you experienced in these meditations?

There was a response from the samadhi towards me and from myself towards the samadhi. The presence of Mother and Sri Aurobindo became more intense during these visits to the samadhi. Afterwards the persistent feeling was that I carried the samadhi within myself, so I do not feel an acute need to be physically face to face with it any longer.

* * *

Some days later I returned to the nursing home to visit Amal. It was Christmas Eve morning and he was dressed in a bright red shirt and was also wearing his ever-present bright and happy smile. On this day, the last interview day, I had no specific questions. We spoke of many things among them being that of feeling the Mother’s presence within. I told him that after my near death experience from an automobile accident in 1962, that the Mother had come to me miraculously bringing me back from the portals of death. At that time she entered my consciousness, opened my psychic being, and since that time has remained permanently in my heart center. I stated that I felt Sri Aurobindo as a vast Presence looking down on me from very high above as the Purusha consciousness. Amal said “Yes, Sri Aurobindo is too large to live within our hearts; we live within him!”

Amal told me that the Mother said if someone came to her even once she did two things: she linked their outer being to their psychic being and the other was that she put out an emanation of herself to go with that person for all of their lifetime. That emanation would go out in accordance with the spiritual needs of the sadhak.

We discussed death further and he said that he spoke to the Mother on a crucial point about going on doing yoga life after life. The Mother said, “Death is not a part of our program!” Amal said he was thunder-struck by this statement. How then did Sri Aurobindo pass away? His passing was called “The Great Sacrifice”. It was not a death in the ordinary sense. Paradoxically, Amal said, with his death the “power of death” died. Death as a regular, fixed principle of evolution no longer exists. Of course people still “die” but overcoming death and decay was the last victory of the work of Sri Aurobindo and the Mother for the earth and it is from the subtle physical plane that this work continues until it is completed.((( In the complete fulfillment of Sri Aurobindo’s vision, physical immortality is seen as a culminating result and there was a belief in the early years of the Ashram that Sri Aurobindo, the Mother and all the (then few) disciples would become immortal. The Mother’s later conversations (as in the Agenda), make clear that she was pushing the limits of her physical consciousness towards the immortal supramental body, but was unsure if it was to be done now. In this conversation with Amal Kiran, some time after Sri Aurobindo’s passing, she affirms the view of a physical supramentalization in this life. Corresponding to this, she contextualizes Sri Aurobindo’s passing as “The Great Sacrifice”, which destroyed the “principle of death”, so that physical death was no longer “necessary” and would eventually disappear, once the human physical consciousness awoke to this fact and eradicated the “habit”. The “death” of the Mother herself, then, may also be seen in this light as a concession to the present human condition.))) Amal said that the Mother and Sri Aurobindo have a “home”, an actual “abode”, on the subtle physical plane. Many ashramites have “visited” this plane and have seen them there.

After this discussion silence fell and we remained in this vast moment of eternity for quite some time. I quietly left with no further words exchanged.

Once more I visited this shining soul before leaving to return to the U.S. The meetings with Amal set in motion a deepening for me of my innermost being and my own personal sadhana. I came away with the feeling of intense joy and gratitude for having been graced to know of his experiences with the Mother and Sri Aurobindo, which brought me ever closer to them in this very personal and intimate sharing.

From The Secret Splendour: Collected Poems of K.D. Sethna (Amal Kiran), pp. 70-71, 77-78.

This Errant Life

This errant life is dear although it dies;

And human lips are sweet though they but sing

Of stars estranged from us; and youth’s emprise

Is wondrous yet, although an unsure thing.

Sky-lucent Bliss untouched by earthiness!

I fear to soar lest tender bonds decrease.

If Thou desirest my weak self to outgrow

Its mortal longings, lean down from above,

Temper the unborn light no thought can trace,

Suffuse my mood with a familiar glow.

For ’tis with mouth of clay I supplicate:

Speak to me heart to heart words intimate.

And all Thy formless glory turn to love

And mould Thy love into a human face.

SRI AUROBINDO’S COMMENTS:

“A very beautiful poem, one of the very best you have written. The last six lines, one may say even the last eight, are absolutely perfect. If you could always write like that, you would take your place among English poets and no low place either. I consider they can rank — these eight lines — with the very best in English poetry.”

Ne Plus Ultra

(To a poet lost in sentimentalism)

A madrigal to enchant her — and no more?

With the brief beauty of her face — drunk, blind

To the inexhaustible vastnesses that lure

The song-impetuous mind?

Is the keen voice of tuneful ecstasy

I To be denied its winged omnipotence,

I Its ancient kinship to immensity

And dazzling suns?

I When mystic grandeurs urge him from behind,

I When all creation is a rapturous wind

I Driving him towards an ever-limitless goal.

Can such pale moments crown the poet’s soul?

I Shall he — born nomad of the infinite heart!

I Time-tamer! star-struck debauchee of light!

I Warrior who hurls his spirit like a dart

I Across the terrible night

I Of death to conquer immortality! —

Content with little loves that seek to bind

His giant feet with perishing joys, shall he

Remain confined

To languors of a narrow paradise —

He in the mirroring depths of whose far eyes

The gods behold, overawed, the unnamable One

Beyond all gods, the Luminous, the Unknown?

SRI AUROBINDO’S COMMENTS:

“This is magnificent. The three passages I have marked [lines 6 through 17] reach a high-water mark of poetic force, but the rest also is very fine. This poem can very well take its place by the other early poem [This Errant Life] which I sent you back the other day, though the tone is different — that other was more subtly perfect, this reaches another kind of summit through sustained height and grandeur.”

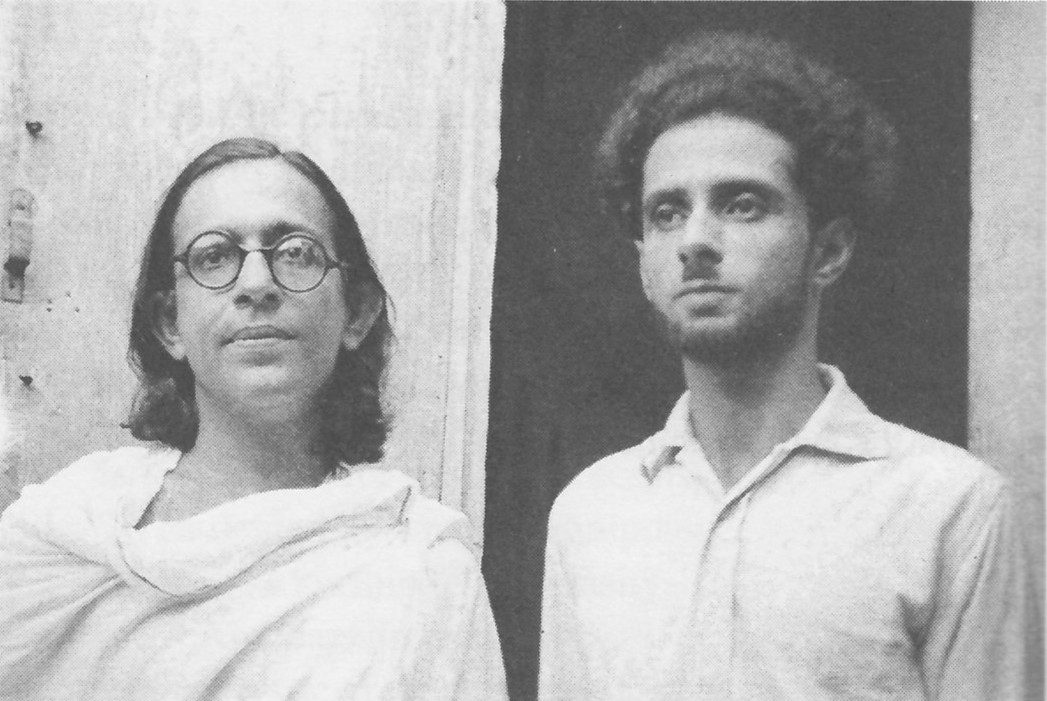

Harin and Amal

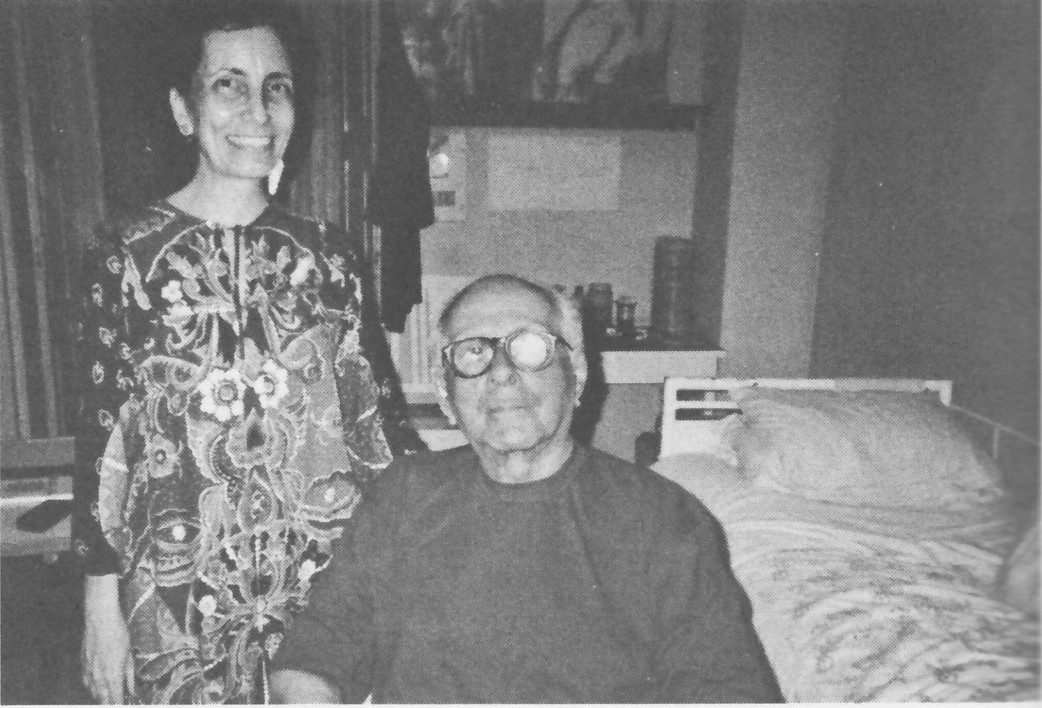

Amal and Minna – Ashram Nursing Home Dec. 1999