“…Then a thing happened suddenly and in a moment I was hurried away to the seclusion of a solitary cell. What happened to me during that period I am not impelled to say, but only this that day after day, He showed me His wonders and made me realise the utter truth of the Hindu religion… day after day I realised in the mind, I realised in the heart, I realised in the body the truths of Hindu religion. They became living experiences to me, and things were opened to me which no material science could explain…. In the communion of Yoga two messages came. The first message said, “I have given you a work and it is to help to uplift this nation. Before long the time will come when you will have to go out of jail; for it is not my will that this time either you should be convicted or that you should pass the time, as others have to do, in suffering for their country. I have called you to work, and that is the Adesh for which you have asked. I give you the Adesh to go forth and do my work…. Something has been shown to you in this year of seclusion, something about which you had your doubts and it is the truth of the Hindu religion. It is this religion that I am raising up before the world, and it is this that I have perfected and developed through the Rishis, saints and Avatars, and now it is going forth to do my work among the nations. I am raising up this nation to send forth my word. This is the Sanatana Dharma, this is the eternal religion which you did not really know before, but which I have now revealed to you. The agnostic and the sceptic in you have been answered, for I have given you proofs within and without you, physical and subjective, which have satisfied you. When you go forth, speak to your nation always this word, that it is for the Sanatana Dharma that they arise, it is for the world and not for themselves that they arise. I am giving them freedom for the service of the world…”

Sri Aurobindo, Uttarpara Speech

No contemporary evidence, not even the most ardent and discerning homage of Sri Aurobindo’s friends and fellow-workers, discloses, so forcibly and lucidly, as does the above extract, the true nature of the work assigned to him by God as the mission of his life. His work for India was a means to his wider work for the world. Politics was but a prerequisite and preliminary to his real mission. The heightening of consciousness and the flood of illumination he had received as a Divine Gift in the Alipore jail pointed to a “religious and spiritual awakening as the next necessity and the next inevitable development” of the national being. The policy and programme of work, formulated and given to the nation, — a programme, which finally led the nation to independence despite its rejection, part rejection and final acceptance at the hands of the political leaders at various stages of the freedom fight — a change of the field of work became imperative. The foundation laid, firm and secure, the architect was called upon to concern himself with the raising of the building. God’s Will must be fulfilled, even if the world knows it not, nor understands.

There are five things in the above extract from the Uttarpara Speech, which deserve careful consideration:

(1) God says to Sri Aurobindo that the work given to him was “to help to uplift this nation”. It was not merely to free the nation from foreign control, but “to uplift it”.

(2) It was not God’s Will that “this time” Sri Aurobindo “should pass the time, as others have to do, in suffering for their country”. No freedom of choice was given to him to share in the suffering of his fellow-workers, no latitude to his personal human sympathies and sense of fellow-feeling. He was led away from suffering to serve His design.

(3) God was raising up Hindu religion — it is the Sanatana Dharma, the eternal religion without any racial or national definition and denomination, that is meant — and He declared that it was now “going forth to do my work among the nations”. Its ultimate objective was not national but international regeneration or, as Vivekananda had prophesied, the regeneration and spiritualisation of mankind.

(4) The exceptional spiritual experiences which had been flooding Sri Aurobindo’s being did not grow in the soft soil of religious faith and certitude, but they took the agnostic and the sceptic in him by storm and unsealing their inner vision, revealed to them the infinite glories of the Spirit.

(5) God commissioned him to go forth and speak to the nation “this word” that it was “for the Sanatana Dharma that they arise”, it was “for the world and not for themselves that they arise”. Here we have, in clear outline, the meaning and mission of the life of Sri Aurobindo, who happened to be for the moment the storm-centre of the political movement of the country.

We have proposed to ourselves a brief and rapid estimate of the aims, ideals and achievements of the three of the greatest political leaders of contemporary India, who worked with Sri Aurobindo — Lal-Bal-Pal, Lala Lajpat Rai, Bal Gangadhar Tilak and Bepin Chandra Pal.

Lokamanya Tilak

That Bal Gangadhar Tilak or Lokamanya Tilak, as he was later called, was the most towering of the three leaders admits of no denying “…He is the very type and incarnation of the Maratha character, the Maratha qualities, the Maratha spirit, but with the unified solidity in the character, the touch of genius in the qualities, the vital force in the spirit which make a great personality readily the representative man of his people…. He has that closeness of spirit to the mass of men, that unpretentious openness of intercourse with them, that faculty of plain and direct speech which interprets their feelings and shows them how to think out what they feel, which are pre-eminently the democratic qualities. For this reason he has always been able to unite all classes of men behind him…. It is… a mistake to think of Mr. Tilak as by nature a revolutionary leader; that is not his character or his political temperament… with a large mind open to progressive ideas he unites a conservative temperament strongly in touch with the sense of his people….”[1]

“…Though he has ideals, he is not an idealist by character. Once the ideal fixed, all the rest is for him practical work, the facing of hard facts, though also the overcoming of them when they stand in the way of the goal, the use of strong and effective means with the utmost care and prudence…. Though he can be obstinate and iron-willed when his mind is made up as to the necessity of a course of action or the indispensable recognition of a principle, he is always ready for a compromise which will allow of getting real work done…. Not revolutionary methods or revolutionary idealism, but the clean sight and the direct propaganda and action of the patriotic political leader insisting on the one thing needful and the straight way to drive at it, have been the sense of Mr. Tilak’s political career… the inflexible will of the patriot and man of sincere heart and thorough action which has been the very grain of his character,… the readiness to sacrifice and face suffering… with a firm courage when it comes….”[2]

In the short obituary tribute to Lokamanya Tilak, which Sri Aurobindo wired from Pondicherry to Bepin Chandra Pal, the editor of the Independent, in response to his request for it, he said: “A great mind, a great will, a great preeminent leader of men has passed away from the field of his achievement and labour. To the mind of his country Lokamanya Tilak was much more, for he had become to it a considerable part of itself, the embodiment of its past efforts and the head of its present struggle for a free and greater life. His achievement and personality have put him amidst the first rank of historic and significant figures. He was one who built much rapidly out of little beginnings, a creator of great things out of an unworked material. The creations he left behind him were a new and strong and self-reliant national spirit, the reawakened political mind and life of a people, a will to freedom and action, a great national purpose. He brought to his work extraordinary qualities, a calm, silent, unflinching courage, an unwavering purpose, a flexible mind, a forward-casting vision of possibilities, an eye for the occasion, a sense of actuality, a fine capacity of democratic leadership, a diplomacy that never lost sight of its aim and pressed towards it even in the most pliant turns of its movement, and guiding all, a single-minded patriotism that cared for power and influence only as a means of service to the Motherland and a lever for the work of her liberation. He sacrificed much for her and suffered for her repeatedly and made no ostentation of his suffering and sacrifices. His life was a constant offering at her altar and his death has come in the midst of an unceasing service and labour…

“Two things India demands, a farther future, the freedom of soul, life and action needed for the work she has to do for mankind;[3] and the understanding by her children of that work and of her own true spirit that the future of India may be indeed India. The first seems still the main sense and need of the present moment, but the second is also involved in them — a yet greater issue. On the spirit of our decisions now and in the next few years depends the truth, vitality and greatness of our future national existence. It is the beginning of a great Self-Determination not only in the external but in the spiritual.[4] These two things should govern our action. Only so can the work done by Lokamanya Tilak find its true continuation and issue.”

Here again, as usual, Sri Aurobindo speaks of the great Self-Determination in the spiritual, and not only of the continuation of the work begun and achieved by Tilak but of its “issue”, “a greater issue”, the work which India “has to do for mankind”. The crown of his life’s mission was always in the forefront of his thought and vision.

Sri Aurobindo’s slashing criticism of the mendicant policy of the Congress must have impressed Tilak, as it had done many others, by its originality and brilliance. When Sri Aurobindo went to Western India to study the revolutionary work carried on there, “he contacted Tilak whom he regarded as the one possible leader for a revolutionary party and met him at the Ahmedabad Congress; there Tilak took him out of the pandal and talked to him for an hour in the grounds expressing his contempt for the Reformist movement and explaining his own line of action in Maharashtra.”[5] Tilak had seen Sri Aurobindo at Baroda in 1901, as we have already stated. From about this time on, a sort of mutual regard began to grow in these two outstanding leaders. Tilak consulted Sri Aurobindo on almost every important political question. At Varanasi, during the Congress session, there was constant consultation between the two, and they stood together as the bulwark and guide of the Nationalist Party at Surat which saw the splitting up of the Congress. The National Conference that held its sittings there to discuss the split and the subsequent line of action, was presided over by Sri Aurobindo. According to Tilak’s biographers, G.P. Pradhan and A.K. Bhagawat, in their book Lokamanya Tilak, “Tilak and Aurobindo were master minds and when they came together each had his impact on the other. Though Tilak did not approve of Aurobindo’s attitude of welcoming repression, he realised the greatness of the ‘prophet of nationalism’ and for the time at least came under the spell of his magnetic personality. Tilak knew that Aurobindo symbolised a new force in Indian politics and he was aware that Aurobindo could and did rouse in hundreds of young men a desire to sacrifice everything for the sake of the motherland.” “To him (Sri Aurobindo) India’s fight for freedom was really an effort for the realisation of her soul. Under Aurobindo’s leadership the New movement transcended the limitations of politics and embraced life…. The association of Tilak and Aurobindo was a happy coincidence… Aurobindo was a visionary and had a mystic touch about him. Tilak was a realist and relied on intellect rather than on intuition.[6] Tilak always advocated the need for manifold means — sādhanānāmanekatā — for getting Swaraj. To him the constitutional methods of the moderates, the direct action particularly the boycott and Swadeshi by the nationalists and the insurrectionary methods of revolutionaries — all these appeared to be necessary in fighting the British.” Tilak gave Sri Aurobindo full and active

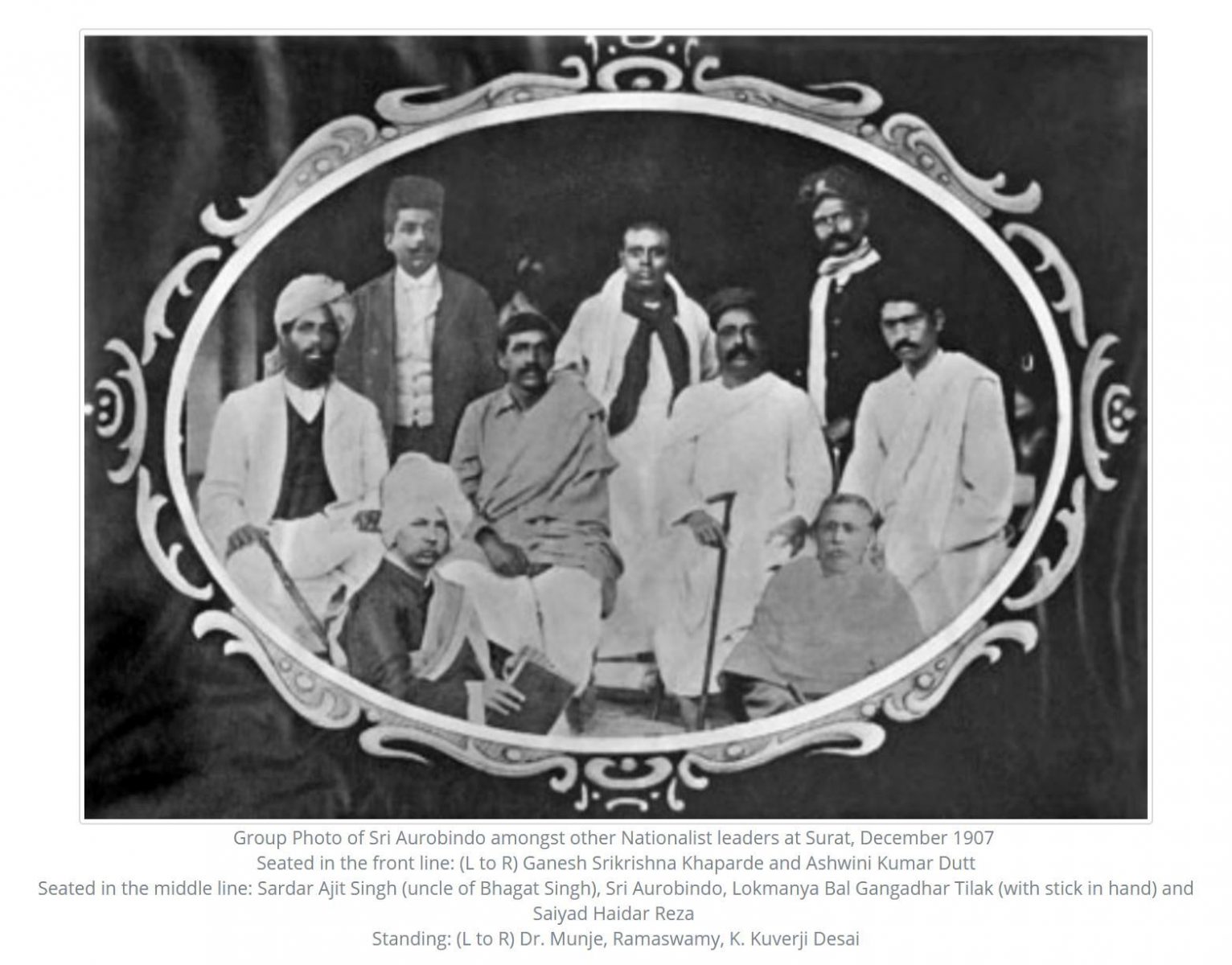

Sri Aurobindo with Tilak and other Nationalists at Surat, 1907

support in his effort to pass the boycott and Swadeshi resolutions in the Calcutta Congress of 1906. Though a realist and constitutionalist by nature, patient and prudent enough to accept half a loaf rather than no bread at all, he never pitched his ideal one inch lower than complete Swaraj, and never ceased fighting for the full loaf. He had come under the spell of Sri Aurobindo’s magnetic personality, as his biographers rightly observe, and imbibed something of his spiritual force and drive, and, though there were differences of vision and views between them, his sturdy realism, directed by his sharp and prodigious intellect, seldom failed to yield precedence to Sri Aurobindo’s intuitive perception and inspired action.[7] The mystic vein of Sri Aurobindo’s nature was so patently and powerfully impressive that no sensitive nationalist could escape its influence. Tilak was fully aware of it, as the following incident recorded by Bapat in his Marathi book, Reminiscences of Tilak, clearly shows:

“In 1917 Ranade (one of the eminent philosophers of his time) saw Tilak who had been released from the Mandalay jail. Tilak had expressed his wish to some of Ranade’s friends about Ranade’s entry into politics, and when the latter saw him, Tilak expressed the same wish to him. But Ranade felt that he had no call for politics. He said: ‘I have already become an active member of the Deccan Education Society and there seems to be no need for my giving it up in favour of politics. Temperamentally I am more inclined towards spirituality (than towards anything else). Besides, according to your view, in order to be an able politician, one should first attain to the state of a sthitaprajña (one who is firmly poised in spiritual wisdom).[8] Before entering the arena of politics, one should be sure of this state in oneslf.’ Tilak remarked with a smile: ‘Aravinda Babu is (also?) a mystic.’” Writing on Tilak’s confidence in Sri Aurobindo’s state of a sthitaprajña, his biographers, Pradhan and Bhagwat, observe: “Tilak knew very well that strategically it was desirable to keep the two planks of civil revolt and revolutionary activity away from each other…. As a leader, however, it was his responsibility to see that all efforts for achieving freedom were carried on in the correct manner, and he therefore gave advice to the leaders of the revolutionary wing. He did not want the decision of the opportune moment to be entrusted to a less mature person who would be swayed by sentiments and affected by some passing phases in politics. He thought that only Aurobindo and himself could take such a momentous decision. He knew that a revolutionary action was too serious a matter to be decided by anyone except those who had attained a philosophic calm of the mind….” This is, indeed, a clear recognition on the part of Tilak of the spiritual realism of Sri Aurobindo’s nature, and a striking tribute to his imperturbable philosophic calm or the radiant placidity of a sthitaprajña.

In spite of the one being led by his reason and intellect, and the other by his intuition and inspiration, Tilak and Sri Aurobindo were the twin most creative forces in contemporary Indian politics — Tilak’s perspicacious realism, his lynx-eyed, resourceful diplomacy, his readiness to drive a compromise[9] to its utmost verge and strike a hard bargain, his pliant, discriminating conservatism, and his unequalled hold on the hearts and minds of his people, paved the way for the achievement of political freedom, and rendered immense help to Sri Aurobindo’s radical endeavours to inculcate the true spirit of Swadeshi, inspire an imperious urge for absolute independence,[10] and rouse the dynamic spirituality of the nation. Tilak’s aim was, not only the conquest of political Swaraj, but the revival of the ancient Dharma of the land-Lajpat Rai’s characterisation of Tilak as “an orthodox revivalist” was not quite just — and the building up of a great nation, rooted in the past and drawing its sap from the ancient heritage, but marching in the vanguard of modern civilisation. He never laid any claim to an illumined foreknowledge of the divine destiny of India and her mission of the spiritual regeneration of the human race. Sri Aurobindo’s aim was, not only preservative, but creative, spiritually creative, the building up of an India greater than she had ever been before, for the fulfilment of the evolutionary destiny of mankind. In this respect, Swami Vivekananda and Sri Aurobindo stand out as the two seers and sculptors of the India that is to be. What Vivekananda intuited and initiated, Sri Aurobindo developed, expanded, and carried to its crowning accomplishment. India of the ageless Light, freed in the body and freed in the soul, shall fulfil the Will of God in the world, and lead humanity to the harmony and perfection of a new, a divine order of existence: this was the message and mission of Swami Vivekananda and Sri Aurobindo.

Lala Lajpat Rai

Lala Lajpat Rai, the lion of the Punjab as he was aptly called, was a fearless fighter in the cause of freedom. It was he, more than anybody else, who kindled the patriotic fire in the hearts of the valiant Punjabis, and moulded by his example and influence some of the most intrepid soldiers of militant nationalism. He was in sympathy with the revolutionaries. In one of his speeches, he said: “Young men, your blood is hot. The tree of the nation calls for the blood. It is watered with blood.”[11] As an Arya Samajist, he had an ethico-religious nostalgia which he incorporated into his revolutionary, extremist politics. Like Tilak, he too, came under the spell of Sri Aurobindo’s “magnetic personality” and imported something of his spiritual fervour into his own creed of nationalism, as Dr. R.C. Mazumdar shows: “He (Sri Aurobindo) regarded patriotism as a form of devotion and expressly said that ‘to the new generations, the redemption of their motherland should be regarded as the true religion, the only means of salvation.’ How this idea permeated the leaders of the new school may be judged from the following extract from an article of Lajpat Rai: ‘In my opinion, the problem before us is in the main a religious problem — religious not in the sense of doctrines and dogmas but religious in so far as to evoke the highest devotion and the greatest sacrifice from us.’”[12] But he too had no pretensions to spiritual vision of the mission and destiny of India and her historic role of bringing the divine Light to the benighted world. He was, however, great as a political leader and commanded the respect of the whole nation by his sincerity and self-sacrifice.

Bepin Chandra Pal

Bepin Chandra Pal was a versatile scholar, an eloquent speaker, a deep and subtle thinker[13], and a consummate theoretician and propagandist. But as an organiser and leader of a national movement, which went on enlarging in magnitude and sweep since 1905, he failed to come up to the mark on account of some intrinsic defects of his nature and temperament. His political life furnishes an interesting study of a sudden rise on to the crest of a tidal wave of national movement, and an equally sudden and tragic fall into the weedy stagnancy of its backwater. In 1901-2, he was a Moderate, avowing his loyalty to the British Imperialism. “Even on his return from the Western world in 1901, he still continued to cherish the old-time belief in the justice and generosity of the British and regard the English rule in India as a sort of a Divine Dispensation…. This deep-rooted conviction of the old guards of the Congress in the moral basis and foundation of British rule in India was still shared by Bepin Chandra during 1901-2….”[14] In 1902, on the occasion of the Shivaji Festival celebrated in Calcutta, he said among other things: “…And we are loyal, because we believe in the workings of the Divine Providence in our national history, both ancient and modern; because we believe that God himself has led the British to this country, to help it in the working out its salvation.”[15] “The radical attitude that Aurobindo Ghose had adopted to the Congress movement even as early as 1893-94 in his writings in the Indu Prakash was still conspicuous by its absence in Bepin Chandra. Even in 1903 the latter could not shake off the spell of traditional Congress politics.”[16]

But a sudden change took place in him, which we can, on the basis of the historical data available, ascribe to three things: (1) his close contact and association with Brahmabandhab Upadhyaya, (2) his closer association with Sri Aurobindo whose “magnetic personality” exerted a powerful influence upon him, and made him overnight a flaming “prophet of nationalism”, and (3) the mighty political agitation which the Partition of Bengal had unleashed. His speeches became full of the fire of militant nationalism, and were buttressed by an impressive display of philosophical knowledge. He soon became, not only a foremost political preacher in Bengal, but thrilled and captured the heart of Madras, and sent sparks of his impassioned nationalism flying all over the country. He was, according to Dr. R.C. Majumdar, a popular preacher of the spiritual nationalism of Swami Vivekananda and Sri Aurobindo. He was a disciple of Yogi Bijoykrishna Goswami, and the spiritual experience, which he had in jail, effected a great change in him, and gave a fiery accent of inspiration to his utterances.[17]

But he was aware of an innate inconstancy in his nature, a lack of firmness and tenacity in the face of difficulties, and it is this that proved his undoing. As soon as Sri Aurobindo was put into prison as an undertrial seditionist and revolutionary, and his contact was broken, Bepin Pal lapsed into his old moderatism and reiterated his avowal of loyalty to the British crown in his paper, Svaraj, which he published in England, and grew as much eloquent in praise of the blessings of the British rule as he had been in its denunciation. “During 1906-08 he had been a most powerful exponent of Indian Swaraj outside the British Empire, but the major trend of his speeches in England during 1908-11 was his attempted reconciliation of the highest National aspirations of Indians with the Imperial system of Great Britain.”[18] It was a rather regrettable climb-down in a leader of his stature and calibre, and it ended in a total collapse, when he opposed the non-cooperation movement of Mahatma Gandhi at Barisal in 1921. The most eloquent exponent of Sri Aurobindo’s programme of Non-cooperation and Passive Resistance became now a bitter critic of Gandhiji’s Non-Cooperation, and “…eleven years later, in 1932, he passed away, amidst grinding poverty, almost unwept, unhonoured and unsung.”[19]

It would be interesting to recall in this context that the goal Sri Aurobindo had put before the country even in 1906 was complete independence outside the British Empire, and the means he had advocated for its attainment was Non-Cooperation and Passive Resistance. The armed insurrection organised on a country-wide scale, which he had preached and attempted at first, fell into the background, as the country did not seem to him to be quite ready for it, and he advocated the former programme of Non-Cooperation and Passive Resistance as being effective enough for the realisation of the goal.

Since the beginning of 1910, when Sri Aurobindo retired from the field of politics to Pondicherry for the working out and realisation of the next higher objective of the national renaissance, the country passed through various phases of the political movement, adopting various programmes from Cooperation and Responsive Cooperation back again to Non-Cooperation, and the goal was pitched higher and higher from Colonial Self-Government and the Irish type of Home Rule to complete Independence free from British control. It is interesting to remember in this connection that Mahatma Gandhi, as a disciple of Gokhale, was at first a whole-hearted cooperator. But little by little events and circumstances opened his eyes to the grim reality of the political situation, and forced him to turn an uncompromising non-cooperator. He showed the same flexibility as Tilak had done on his return from the Mandalay prison.[20] The great political issue of 1920 was whether the Congress leaders should seek election to the Legislative Councils according to the provisions of the 1919 reforms. Gandhiji was willing to advise the Congress to contest the elections, but in the meantime the Jallianwala Bag massacre and the Khilafat wrong gave him a rude shock and disillusioned him. He lost all his faith in British justice, and decided to non-cooperate with the Government. He succeeded in enlisting the support of many Congressmen for his non-cooperation movement, and presented a resolution, embodying his programme, in the special Calcutta session of the Congress in 1920. “He intended the movement to be based on the moral issues arising out of the British injustice concerning the Khilafat question and the Punjab issue. It must be remembered that Gandhiji’s experience as a popular leader had not until this time been primarily political. Rather his efforts in South Africa and his early work in India were basically humanitarian. This may account for the rather amazing fact that he did not originally include Swaraj as a reason, let alone the reason, for the initiation of national non-cooperation. Gandhiji advocated his programme because he believed that the Khilafat and Punjab issues were moral issues upon which the nation should take action. He did not initially accept the idea that British colonial rule in India was itself the greatest moral issue of the day. It was left for one of Tilak’s colleagues, Vijayaraghavachari, to remind the young leader that for over twenty years the Nationalists had worked for one great all-encompassing goal — Swaraj. He reminded Gandhiji that Swaraj was the great moral issue before India, and urged that Swaraj be incorporated as both the goal of and the motivating reason for the non-cooperation movement. Gandhiji readily agreed to this.”[21] Referring to this incident, Gandhiji writes in his autobiography, The Story of my Experiments with Truth, “In my resolution non-cooperation was postulated only with a view to obtaining redress of the Punjab and the Khilafat wrongs. That, however, did not appeal to Sj. Vijayaraghavachari. ‘If non-cooperation was to be declared, why should it be with reference to particular wrongs? The absence of Swaraj was the biggest wrong that the country was labouring under; it should be directed,’ he argued. Pandit Motilalji also wanted the demand for Swaraj to be included in the resolution. I readily accepted the suggestion, and incorporated the demand for Swaraj in my resolution.”[22]

Thus Non-cooperation and Passive Resistance came to be finally accepted as the policy and programme par excellence, and the “Quit India” movement of a later date (1942) clinched the goal as absolute independence free from British control.

A question naturally arises here: How did Sri Aurobindo give such a full-fledged plan, and fix what appeared even to the greatest of contemporary political leaders as rather an impracticable goal, so early as 1906, when the freedom fight had but just begun? There should be nothing astounding in it, if we remember that the Yogi can command a prevision of the future happenings, which even to the developed rational intelligence remain only a matter of vague surmise or imaginative dream. The poet or artist sometimes receives this kind of intuitive vision or immediate inner apprehension. It flashes across his consciousness in a moment of inspiration. But in an advanced Yogi these sporadic flashes resolve themselves into a steady current of lustre.

Such an inspired moment the poet-patriot C.R. Das had, when in 1909 he prophesied before the judge who was trying Sri Aurobindo in the Alipore Case on the trumped-up charge of sedition and revolutionary action: “The able and prophetic advocacy of Chittaranjan (C.R. Das) raised the trial almost to an epic level. His famous appeal to the court still rings in the ears because it has proved to be true to the letter. He said to Mr. Beachcroft, who was the judge in the case, ‘My appeal to you is this, that long after the controversy will be hushed in silence, long after this turmoil and the agitation will have ceased, long after he is dead and gone, he will be looked upon as the poet of patriotism, as the prophet of nationalism and the lover of humanity.[23] Long after he is dead and gone, his words will be echoed and re-echoed, not only in India but across distant seas and lands… ”[24]

The above quotation is not only a string of words, issuing like flakes of fire from a burning moment of inspiration, it suggests the deep impression Sri Aurobindo’s personality had made upon the sensitive mind of C.R. Das. What was there in Sri Aurobindo in 1908-9 on the basis of which one could predict that “his words would be echoed and re-echoed not only in India but across distant seas and lands”?

Subhash Chandra Bose, the chief lieutenant of C.R. Das, — C.R. Das became later in 1918 the foremost pilot of Bengal politics and one of the greatest leaders of the Indian National Congress — writes in his book, An Indian Pilgrim: “In my undergraduate days Arabindo Ghosh was easily the most popular leader in Bengal, despite his voluntary exile and absence from 1909. His was a name to conjure with…. On the Congress platform he had stood up as a champion of left-wing thought and a fearless advocate of independence at a time when most of the leaders, with their tongues in their cheeks, would talk only of colonial self-government. A mixture of spirituality and politics had given him a halo of mysticism…. When I came to Calcutta, Arabindo was already a legendary figure. Rarely have I seen people speak of a leader with such rapturous enthusiasm…. All that was needed in my eyes to make Arabindo an ideal guru for mankind[25] was his return to active life.”

[1] Bankim-Tilak-Dayananda by Sri Aurobindo.

[2] Bankim-Tilak-Dayananda by Sri Aurobindo.

[3] Italics are ours.

[4] Italics are ours.

[5] Sri Aurobindo on Himself and on The Mother, p. 45.

[6] Nevinson speaks of Tilak’s shrewd political judgment and Sri Aurobindo’s spiritual elevation.

[7] Lokamanya Tilak, by G.P. Pradhan and A.K. Bhagwat.

[8] Tilak’s Guru, Anna Saheb Patwardhan, who was a Yogi, presided over the meeting held at Gaekwarwada (Tilak’s residence) at Poona in which Sri Aurobindo was the principal speaker. It is said that Patwardhan predicted the yogic greatness of Sri Aurobindo and considered him to be the greatest of all contemporary leaders. He had a private interview with Sri Aurobindo just after the said meeting, but what they talked about in that interview remained a secret.

[9] “I know full well that in politics it is no fault to compromise at times without leaving one’s principles. I shall not stretch till the breaking point. The moment I think the breaking point is reached, I shall loosen my hold and effect a compromise. In politics I am all for compromise.” — Lokamanya Tilak by Praddhan & Bhagwat, p. 255 (Jaico).

[10] “Sri Aurobindo was the first to use its (of the word Swaraj) English equivalent ‘independence’ and reiterate it constantly in the Bande Mataram as the one and immediate aim of national politics.” — Sri Aurobindo on Himself and on The Mother, p. 30.

[11] Quoted by R.C. Majumdar in his History of the Freedom Movement in India, Vol. I, p. 475.

[12] The Genesis of Extremism by Dr. R.C. Majumdar in Studies in the Bengal Renaissance. Even Tilak once wrote: “God and our country are not different. In short, our country is one form of God.”

[13] “…the most powerful brain at work in Bengal.” — Sri Aurobindo

[14] Bepin Chandra Pal and India’s struggle for Swaraj by Prof. Haridas Mukherjee and Prof. Uma Mukherjee.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] “…The issues of this struggle involve the emancipation of India and the salvation of Humanity.” — Bepin Chandra Pal

[18] Bepin Chandra Pal and India’s Struggle for Swaraj by Prof. Haridas Mukherjee and Uma Mukherjee.

[19] Bepin Chandra Pal and India’s Struggle for Swaraj by Prof. Haridas Mukherjee and Uma Mukherjee.

[20] Tilak started the All-India Home Rule League, joined forces with Annie Besant, and preached Responsive Cooperation. In view of the changed circumstances and the accommodating attitude of both the people and the Government, Sri Aurobindo approved of Tilak’s new tactical move.

[21] The Legacy of the Lokamanya by Theodore L. Shay.

[22] Quoted by T.L. Shay in his book, The Legacy of Lokamanya.

[23] “…patriotism is good, excellent, divine, only when it furthers the end of universal humanity. Nationality divorced from humanity is a source of weakness and evil, and not of strength and good.” — Bande Mataram

- “Your first duties, first not in point of time but of importance — because without understanding these you can only imperfectly fulfil the rest — are to Humanity.”

“Love Humanity. Ask yourselves whenever you do an action in the sphere of your Country, or your family, If what I am doing were done by all and for all, would it advantage or injure Humanity? and if your conscience answers, it would injure Humanity, desist; desist, even if it seems to you that an immediate advantage for your Country or your family would ensue from your action. Be apostles of this faith, apostles of the brotherhood of nations, and of the unity of the human race…” — Mazzini (Duties of Man)

[24] Mahayogi R.R. Diwakar, 2nd Edition (Bhavan’s Book University).

[25] Italics are ours.