The first house where Sri Aurobindo stayed form April to September 1910

The first house where Sri Aurobindo stayed form April to September 1910

I HAVE said that this cemetery that was Pondicherry had been infested by ghosts and goblins. These had a special category known ordinarily as spies. The word “spy” carries with it, as you know, an association of all that is low and disgusting and unspeakable, things of dark import. But did you know that the word is pure Sanskrit? It was spasa in the old Vedic language. The Vedic Rishi describes Indra as sending out these spasa to trace the movements of his enemies, the forces of evil that clustered round the god. So, the Vedic gods had their spies, just as the modern British government had theirs, though of course there was bound to be a certain difference. These government spies tried to collect information as to who came to our houses, who were the people who met us, what places we frequented and how our guests spent their time. That was why Motilal (Motilal Roy of the Pravartak group in Chandernagore), when he first came to Pondicherry, had to come dressed as an Anglo-Indian, and he never entered our house, the Raghavan House of today, except by the back door and under cover of darkness after nightfall.

In fact, all of us on our first arrival here had to come under false names, the only exception being Moni (Suresh Chakravarti). He did not have to, for he had not been one of the marked men like the rest of us and his name had not been associated with any political trouble, as he was too young for that at the time. And in any case it would not have been wise to give him a false name, to save him from the clutches of the law, for it was decided to rent our houses in his name and it was he again who was to act on our behalf in all official matters. Sri Aurobindo called himself Jatindranath Mitra, though only for a short while. It was under this pseudonym that he sailed from Calcutta as a passenger on the “Dupleix” and had presented himself before the doctor for the medical examination. The fun of it was that the doctor had no suspicion as to whom he was going to examine, although he did exclaim on hearing Sri Aurobindo’s accent, “You seem to speak English very well!”, to which Sri Aurobindo replied, “Yes, I was in England for sometime.” Sometime indeed – fourteen years! My name was Manindranath Roy, and eventually I came to be known as Monsieur Roy; some of my local friends of those days still know me as such’ and call me by that name. Roy and “Sacra” (that is, short for Chakravarti in French) became quite well-known figures both in town and elsewhere on account of their football. Bejoy was Bankim Basak – Basak for short – the noted half-back in our football team.

The British Indian police set up a regular station here, with a rented house and several permanent men. They were of course plain-clothes men, for they had no right to wear uniform within French territory. They kept watch, as I have said, both on our visitors and guests as well as on ourselves. Soon they got into a habit of sitting on the pavement round the corner next to our house in groups of three or four. They chatted away the whole day and only now and again took down something in their note-books. What kind of notes they took we found out later on, when, after India had become independent and the French had left, some of these notes could be secured from the Police files and the confidential records of Government. Strange record, these: the police gave reports all based on pure fancy, they made up all sorts of stories at their sweet will. As they found it difficult to gather correct and precise information, they would just fabricate the news.

Nevertheless, something rather awesome did happen once. We had by then shifted to the present Guest House. There were two new arrivals. One was a relative of Bejoy’s, Nagen Nag, who had managed to get away from his family and had come to stay here on the pretext of a change of air for his illness. The other was a friend and acquaintance of his who had come with him as a companion and help; his name was Birendra Roy.

One day, this Birendra suddenly shaved his head. Moni said he too would have his head shaved, just because Birendra had done it. That very day, or it was perhaps the day after, there occurred a regular scene. We had as usual taken: our seats around Sri Aurobindo in the afternoon. Suddenly, Biren stood up and shouted, “Do you know who I am? You may not believe it, but I am a spy, a spy of the British police. I can’t keep it to myself any longer. I must speak out, I must make the confession before you.” With this he fell at Sri Aurobindo’s feet. We were stunned, almost dumbfounded. As we kept wondering if this could be true, or was all false, perhaps a hallucination or some other illusion – maya nu matibhramo nu – Biren started again, “Oh, you do not believe me? Then let me show you.” He entered the next room, opened his trunk, drew out a hundred rupee note and showed it to us. “See, here is the proof. Where could I have got all this money? This is the reward of my evil deed. Never, I shall never do this work again. I give my word to you, I ask your forgiveness…” No words came to our lips, all of us kept silent and still.

This is how it came about. Biren had shaved his head in order that the police spies might spot him out as their man from the rest of us by the sign of the shaven head. But they were nonplussed when they found Moni too with a shaven head. And Biren began to suspect that Moni, or perhaps the whole lot of us, had found out his secret and that Moni had shaved on purpose. So, partly out of fear and partly from true repentance, for the most part no doubt by the pressure of some other Force, he was compelled to make his confession.

After this incident, the whole atmosphere of the house got a little disturbed. We were serious and worried. How was it possible for such a thing to happen? An enemy could find his entry into our apartments, an enemy who was one of ourselves? What should be done? Bejoy was furious, and it was a job to keep him from doing something drastic. However, within a few days, Biren left of his own accord and we were left in peace. I hear he afterwards joined the Great War and was sent to Mesopotamia with the Indian army,

During the Great War, Bejoy had his spell of bad luck. That makes another story. I have said the British Indian police had set up a post here. It was placed in charge of a senior official, no less a person than a Superintendent of Police. He was a Muslim, named Abdul Karim if I remember aright, a very efficient and clever man, like our old friend Shamsul Alam of the Calcutta Police. We used to go to a friend’s house very often, particularly myself. This gentleman too, we found, was a visitor there and we used to meet him as if by accident. He was very nice and polite in his manners. He even expressed a desire once to have Sri Aurobindo’s darsan so that he might pay his respects. Sri Aurobindo did not refuse, he was given the permission. The gentleman arrived with a huge bouquet by way of a present and had the darsan.

The three of us, namely, Moni, Saurin and myself, who had returned to Bengal after an interval of four years, had to hasten back here almost immediately owing to the outbreak of War, for there was a chance that old ‘criminals’ like us would again be shut up in jail. As we had come back, Bejoy said he wished to go, for he too wanted to have a change. He would return after paying a short visit to his people. He said he had been away for so long. But the question was: would it be all right for him to go? What did the French Government think? What would they advise? It was in formally ascertained from the Governor that he did not consider it advisable to leave here, for the intentions of the British authorities were not above suspicion. Abdul Karim too was sounded as to their intentions. He said the British Government meant us no harm, for he was well aware that we were saintly people engaged in sadhana alone, and so on. But Sri Aurobindo had serious doubts. Bejoy however was a head-strong man. He got eager to go and set foot on British territory, that is, offer his neck to the scaffold. And that is what happened. The moment he crossed the border and entered British Indian territory, he found the police waiting. They put him in handcuffs, and for the next five years, that is, till after the War was over, he was held in detention. Once he had managed to get away earlier with only a year’s custody in jail; this time it was not so easy.

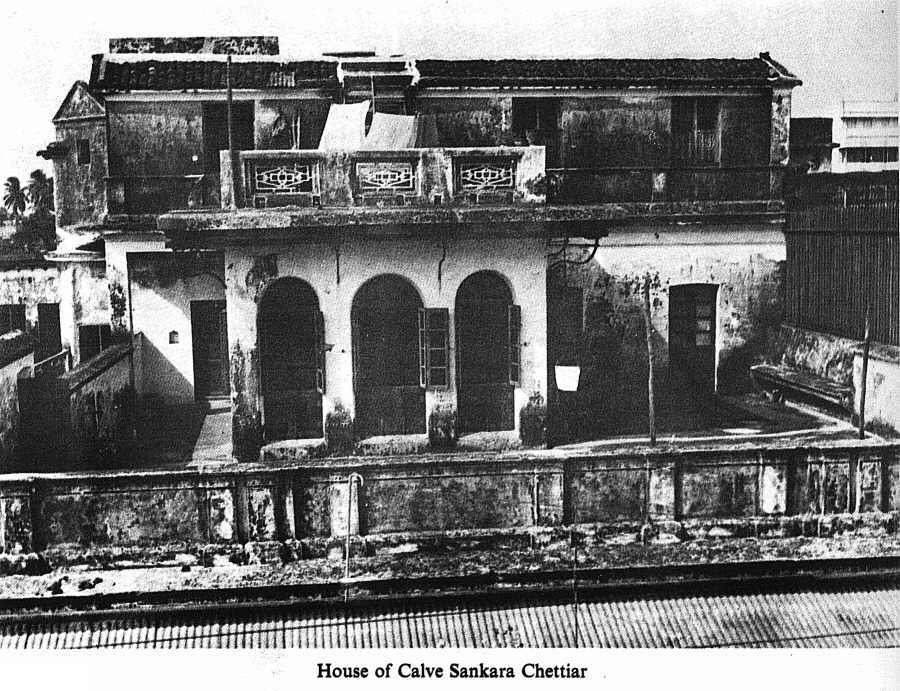

But why dwell on this dark tale of the lawless wilds and the demons and beasts. Their ranks are still powerful and I do not wish to add to their strength by talking about them. Now let me say a few nice things, about some good people, for such people too had their abode here. At the very outset I should speak of the Five Good Men. It is quite possible that there was a law in French India that applied to foreigners. But now the law was made stringently applicable to refugees from our own country. It was laid down that all foreigners, that is, anyone who was not a French citizen, wanting to come and stay here for some time must be in possession of a certificate from a high Government official of the place from where he came, such as a Magistrate in British India, to the effect that he was a well-known person and that there was nothing against him; in other words, he must be in possession of a “good conduct” certificate. Or else he must produce a letter to the same effect signed by five gentlemen of standing belonging to Pondicherry. I need hardly say that the first alternative was for us quite impossible and wholly out of the question. We chose the second line, and the five noble men who affixed their signatures were these: (1) Rassendren (the father of our Jules Rassendren), (2) De Zir Naidu, (3) Le Beau, (4) Shanker Chettiar (in whose house Sri Aurobindo had put up on first arrival) and (5) Murugesh Chettiar. The names of these five should be engraved in letters of gold. They had shown on that occasion truly remarkable courage and magnanimity. It was on the strength of their signatures that we could continue to stay here without too much trouble.

The story of these local leaders reminds me of another incident. When I came here first, I had to adopt a subterfuge in order to ward off all suspicion. I posed as if I had come from Chandernagore, that is, from one part of French India to another, as a messenger carrying a letter from one political leader to another. I had a letter from the leader of a political party in Chandernagore to be delivered by hand to his opposite number in Pondicherry. The gentleman for whom I brought the message was called Shanmugabhelu; I forget the name of the Chandernagore gentleman. The letter suggested that he might help me find suitable accommodation for my stay here. I came and saw Mr. Shanmugabhelu at his residence with that letter. My pronunciation of the name as Shanmugabhelu must have shocked the Tamil people present there! I found the huge Mr. Gabhelu leaning on an easy-chair, surrounded by his henchmen and discoursing in tones of thunder – although the thunder must have been of the dry autumnal sort, for his party was Radical Socialist, something like our Moderate Nationalists who shouted but produced nothing. He spoke in clear French. “Sommesnous des citoyens francais, ou non?” – “Are we French citizens, or are we not?” – he shouted. This was a plaint addressed to the French authorities, a petition and protest: “Where exactly do we stand here in the matter of rights?”

Among our first acquaintances in Pondicherry were some of the young men here. The very first among them was Sada – you have known him, for he kept up with us till the end. Next cameBenjamin, Rassendren and a few others. Rassendren has joined us again at the end of his career; in his early days he had been our playmate. Gradually, they formed a group of Sri Aurobindo’s devotees. The strange thing about it was that they were all Christians. We did not have much of a response from the local Hindus; perhaps they were far too orthodox and old-fashioned. The Cercle Sportif was our rendezvous. There we had games, we arranged picnics, as you do today, we staged plays, and also held study circles. Only students took part.

Afterwards, when the Mother came in 1914, it was with a few men chosen from out of this group that she laid the first foundation of her work here; they formed the Society called “L’Idée Nouvelle”. Already, in her Paris days, a similar group had been formed around her, a group that came to be known as the Cosmique, a record of whose proceedings has appeared in part in the Mother’s Words of Long Ago (Paroles d’Autrefois). Here, in Pondicherry, she started building up an intimate circle of initiates simultaneously with the publication of the Arya.

Let me speak now of a strange incident lest you should miss the element of variety in our life of those days. We stayed at the Guest House then. The Mother had finally arrived. The Great War was over, I mean the first one. And with the declaration of Peace, nearly all the political prisoners in India had been released. Barin, Upen, Hrishikesh had all come back from the Andamans, although they were still hesitating as to whether they should join us here in the life of yoga or continue for some time longer their work in the outside world.

One day, something rather extraordinary happened. Into our compound there came a Sannyasin. He had a striking appearance, tall and fair, a huge turban wrapped round his head, a few locks of hair hanging down upon his shoulders. There were three or four disciples too. He begged for Sri Aurobindo’s darsan. But the darsan turned out to be somewhat spectacular. There he disclosed his identity. Concealed behind the thick cloak of Sannyasa was our old comrade Amarendra, Amarendranath Chatterji, the noted terrorist leader for whose capture the British Government had been moving heaven and earth, that is, the worlds of the dead and the living, and also raising hell in the world of the underground. Perhaps they had set a price on his head too. And here he was in person! There was a wave of joy and excitement, mingled with some apprehension as well, for no one knew what the British or the French would do in case the news got abroad.

Amarendra had suddenly disappeared one day. He lived the life of a primitive savage in the jungles of Assam; he had been selling poultry and eggs at the steamship stations along the rivers of East Bengal, in the garb of a Muslim complete with Lungi and Fez. And so many other things he had done just in order to avoid the Government’s vigilant eye. It was a long romantic tale. Finally, he made himself a Sannyasin, became a Guruji. Near Tanjore he set up his Ashram. Disciples gathered, his mantras and teachings brought him fame; he styled himself, if I remember aright, Swami Kaivalyananda. The British Government were completely fooled.

The Swamiji, our Amarendra, came here to obtain Sri Aurobindo’s instructions as to what to do next. This, as I have said, was after the end of the War, when practically all the political prisoners had been set free and even those deported to the Andamans had been allowed to come back. He wished to know if he could now disclose himself and also what he was to do afterwards. He was advised to go back to Calcutta and await the turn of events for a while. The Swamiji now ordered his disciples back to the Ashram and. said that he would like to live in solitude for some time.

That was the end of Swami Kaivalyananda. He had had his nirvana and his place was taken by Amarendra Chatterji. The disciples had in the meantime gone back to their Ashram. There they kept waiting, but the months passed without any news of Guruji. They came here at last to find out where their Guruji was. Where indeed?

I met Amarendra for the last time just before I came away to Pondicherry for good. I had been to his shop. It was a drapery stores known as the Workers’ Cooperative that served as a veil and a meeting ground for terrorist activities. He knew all about me and also that I was on my way to Pondicherry. As a parting gift, he handed me a shawl from his Stores, adding, “Payable when able.” I distinctly remember the phrase. I came in touch with him again long after this. He became a devotee and disciple of Sri Aurobindo and the Mother and remained a faithful follower till his death.

It will not be out of place here to say something about the sort of education and training we received in those early days of our life in Pondicherry. One of the first needs we felt on coming here was for books, for at that time we had hardly anything we could call our own. We found that at the moment Sri Aurobindo was concentrating on the Rigveda alone and we managed to get for him two volumes of the original text. He had of course his own books and papers packed in two or three trunks. It was felt we might afford to spend ten rupees every month for the purchase of books. We began our purchases with the main classics of English literature, especially the series published in the Home University Library and the World Classics editions. Today you see what a fine Library we have, not indeed one but many, for there is a Library of Physical Education, there is a Medical Library, there is a Library for the School, and there are so many private collections. All this had its origin in the small collections’ we began every month. At first, the books had to lie on the floor, for we had nothing like chairs or tables or shelves for our library” I may add that we had no such thing as a bedding either for our use. Each of us possessed a mat, and this mat had to serve as our bedstead, mattress, coverlet and pillow; this was all our furniture. And mosquito curtains? That was a luxury we could not even dream of. If there were too many mosquitos, we would carry the mats out on to the terrace for a little air, assuming, that is, that there was any. Only for Sri Aurobindo we had somehow managed a chair and a table and a camp cot. We lived a real camp life. I should add that there were a few rickety chairs too, for the use of visitors and guests. And lights? Today you see such a profusion of electric lighting in every room and courtyard; we have mercury lights and flash lights and spotlights and torch lights; we are even getting well into the limelight! There is light everywhere, “all here is shining with light”, sarvamidam vibhati. In those days, on the other hand, we did not even have a decent kerosene lamp or lantern. All I can recall is a single candlestick, for the personal use of Sri Aurobindo. Whatever conversations or discussions we had after nightfall had to be in the dark; for the most part we practised silence. The first time there was an electric connection, what a joy it gave us! It came like a revelation almost. We were in the Guest House at the time, had shifted there only a, little while ago. We were out one afternoon for our games (that is, football), and it was already dark by the time we returned. As we opened the door and entered the compound, what a surprise it was! The place was full of light, there were lights everywhere, a real illumination. The electricians had come and fitted the connections whilst we had been away. They had fitted as many as four points for the entire building, the Guest House that you see, two for the first floor and two downstairs!

We were able to purchase some French books at a very cheap rate, not more than two anna; for each volume in a series. We had about a hundred of them, all classics of French literature. I find a few of them are still there in our Library. Afterwards, I also bought from the second-hand bookshops in the Gujli Kadai area several books in Greek, Latin and French. Once I chanced on a big Greek lexicon which I still use.

Gradually, a few books in Sanskrit and Bengali too were added to our stock, through purchase and gifts. As the number of books reached a few hundred, the problem was how to keep them. We used some bamboo strips to make a rack or book-stand along the walls of our rooms; the “almirahs” came later. I do not think there were any “almirahs” at all so long as we were in the Guest House. They came after the Mother’s arrival, when we shifted with our books to the Library House. That is why it came to be called the Library House.

This account would be incomplete without a few details as to our housekeeping. As to the furniture, I have already said the mat alone did duty for everything. Of servants we had only one; he did the shopping. But as we did not know his language, we had just memorised a few words connected with shopping and we somehow managed to make him understand with the help of these words and a good deal of gestures. Bejoy had his standing instructions: “meen moon anna” (fish three annas) – it was lucky meen in Tamil is the same as in Bengali – “if ille, then nal anna” (if not, then four annas), the Tamil equivalents of “if” or “then” were beyond the range of our knowledge. Today we have practically one servant per head, thanks to the boundless grace of the Mother. Sri Aurobindo used to smile and make the comment, “We have as many servants as there are sadhaks here.”

We did the cooking ourselves and each of us developed a speciality: I did the rice, perhaps because that was the easiest. Moni took charge of dal (pulses), and Bejoy being the expert had the vegetables and the curry. What fell to the lot of Saurin I do not now remember – Saurin was a brother-in-law of Sri Aurobindo, a cousin of Mrinalini’s. Perhaps he was not in our Home Affairs at all; his was the Foreign Ministry, that is, he had to deal with outsiders. We had our first real cook only after the Mother’s arrival, by which time our numbers had grown to ten or twelve. There was a cook who had something rather special about her: she had been to Paris and, made quite a name there on account of certain powers of foreseeing the future and other forms of occult vision which she possessed. The Mother had these powers tested in the presence of some of us. She was asked to take a bath and put on clean clothes and then made to sit with us. The Mother took her seat in a chair. We did a little concentration in silence and then the Mother asked her, “What do you see? Do you see anything about anybody present here?” and so on. She gave truly remarkable answers on several occasions. And yet she had had no sort of formal education, she was absolutely illiterate, had only picked up some French by ear. Another cook who came later has become, as you know, quite a celebrity thanks to his spiritist performance. The story has become well-known, it is now almost a classic. Sri Aurobindo has referred to it, the Mother has spoken and written about it, the well-known French poet and mystic Maurice Magre who had been here and lived in the Ashram for some time has recorded it in one of his books. You must have heard or read what Sri Aurobindo and the Mother have said on the subject. I do not wish to add anything of my own, for I was not an eye-witness; I had been away in Bengalfor a while.

Now that we are on this topic of cooks and cooking, let me add a few words about myself in this connection. I had, as I said, some practice in the work of the kitchen and I took it up again later on. For some time – we were about fifty in all by then – I did some serving in addition to cooking once a week. What kind of cooking was that? In those days, we used to have pudding, payas, for dinner three times a week, ordinary rice pudding, fried rice pudding, and tapioca pudding. I did the tapioca. It was rather in the fitness of things that the hands that had once been used to making bombs should now do some sweets.

At one time, one of our main subjects of study was the Veda. This went on for several months, for about an hour every evening, at the Guest House. Sri Aurobindo came and took his seat at the table and we sat around. Subramanya Bharati the Tamil poet and myself were the two who showed the keenest interest. Sri Aurobindo would take up a hymn from the Rigveda, read it aloud once, explain the meaning of every line and phrase and finally give a full translation. I used to take notes. There are many words in the Rigveda whose derivation is doubtful and open to differences of opinion. In such cases, Sri Aurobindo used to say that the particular meaning he gave was only provisional and that the matter could be finally decided only after considering it in all the contexts in which the word occurred. His own method of interpreting the Rigveda was this: on reading the text he found its true meaning by direct intuitive vision through an inner concentration in the first instance, and then he would give it an external verification in the light of reason, making the necessary changes accordingly.

Sri Aurobindo has taught me a number of languages. Here again his method has often evoked surprise. I should therefore like to say something on this point. He never asked me to begin the study of a new language with primary readers or children’s books. He started at once with one of the classics, that is, a standard work in the language. He used to say that the education of children must begin with books written for children, but for adults, for those, that is, who had already had some education, the reading material must be adapted to their age and mental development. That is why, when I took up Greek, I began straightway with Euripides’ Medea, and my second book was Sophocles’ Antigone. I began a translation of Antigone into Bengali and Sri Aurobindo offered to write a preface if I completed the translation, a preface where, he said, he would take up the question of the individual versus the state. Whether I did complete the translation I cannot now recollect. I began my Latin with Virgil’s Aeneid, and Italian with Dante. I have already told you about my French, there I started with Molière.

I should tell you what one gains by this method, at least what has been my personal experience. One feels as if one took a plunge into the inmost core of the language, into that secret heart where it is vibrant with life, with the quintessence of beauty, the fullness of strength. Perhaps it was this that has prompted me to write prose-poems and verse in French, for one feels as if identified with the very genius of the language. This is the method which Western critics describe as being in medias res, getting right into the heart of things. One may begin a story in two ways. One way is to begin at the beginning, from the adikada and Genesis, and then develop the theme gradually, as is done in the Ramayana, the Mahabharata, the Bible. The other method is to start suddenly, from the middle of the story, a method largely preferred by Western artists, like Homer and Shakespeare for instance.

But it was not found possible for Sri Aurobindo to continue with his own studies or even to help us in ours. For, as I have already hinted, our mode of living, our life itself took a different turn with the arrival of the Mother. How and in what direction? It was like this. The Mother came and installed Sri Aurobindo on his high pedestal of Master and Lord of Yoga. We had hitherto known him as a dear friend and close companion, and although in our mind and heart be had the position of a Guru, in our outward relations we seemed to behave as if he were just like one of ourselves. He too had been averse to the use of the words “Guru” and “Ashram” in relation to himself, for there was hardly a place ‘in his work of new creation for the old traditional associations these words conveyed. Nevertheless, the Mother taught by her manner and speech, and showed us in actual practice, what was the meaning of disciple and master; she has always practised what she preached. She showed us, by not taking her seat in front of or on the same level as Sri Aurobindo, but by sitting on the ground, what it meant to be respectful to one’s Master, what was real courtesy. Sri Aurobindo once said to us, perhaps with a tinge of regret, “I have tried to stoop as low as I can, and yet you do not reach me.”

It was the Mother who opened our eyes and gave us that vision which made us say, even as Arjuna had been made to say:

sakheti matva prasabham yaduktam

he Krsna he yadava he sakheti

ajanata mahimanam tavedam

maya pramadat pranayena vapi.

yaccavahasartham asatkrto’si

viharasayyasanabhojanesu

eko’thavapyacyuta tatsamaksam

tatksamaye tvamahamaprameyam

“By whatever name I have called you, O Krishna, O Yadava, O Friend, thinking in my rashness that you were only a friend, and out of ignorance and from affection, not knowing this thy greatness; whatever disrespect I have shown you out of frivolity, whether sitting or lying down or eating, when I was alone or when you were present before me, – may I be pardoned for all that, O thou Infinite One.”