THE MOTHER’S BIRTHDAY MESSAGES

TO NOLINI

(Translated from original French)

Happy Birthday

Nolini!

With my blessings for a decisive

year of realisation in light

and harmony, truth and love.

13.1.65

The Mother

Happy Birthday

Nolini

in silent endurance, one step

forward towards the victory,

with the eternal love.

13.1.66

The Mother

Happy Birthday

Nolini

for taking another step on the

luminous path leading to the

Divine Realisation in Peace,

love and joy.

13.1.67

The Mother

Nolini

Happy Birthday! Happy New

Year in the light, peace, joy and

love with my love and affection

and blessings.

13.1.68

The Mother

Happy Birthday

Nolini

en route towards the superman

with my love and affection and

blessings.

13.1.69

The Mother

Happy Birthday

Nolini

and all my love and affection

and blessings in the light,

consciousness and joy.

13.1.70

The Mother

Happy

Birthday Nolini

with my love and affection for a life

of collaboration and my blessings

for the prolonged continuation of

this happy collaboration in peace

and love.

13.1.71

The Mother

Happy Birthday

Nolini

with my love and affection and

blessings.

13.1.72

The Mother

Happy Birthday

Nolini.

With my affection, my trust and my blessings.

Go forward towards the Realisation.

13.1.73

The Mother

INDIRA GANDHI’S MESSAGE

Prime Minister’s House

New Delhi

In flight

Delhi – Dabolim

February 11, 1984

Dear Shri Gupta,

I am so deeply saddened by the news of your father’s passing away that I do not know what words to write.

Nolinida was a father not just to you but to the Ashram. I hope his successor will be able to give proper guidance and keep up to the high standards set by Nolinida and the directions given by The Mother. Nolinida was a man of spiritual attainment and quality. India will miss his benign presence. He radiated peace.

You and your family and the inmates of the Ashram have my sincere sympathy and condolences.

Yours sincerely,

(Indira Gandhi)

Shri Samir Kanta Gupta,

Sri Aurobindo Ashram,

Pondicherry.

PAUL RICHARD’S APPRECIATION

A DIVINE WARRIOR

During our Marathon interview the great French savant Paul Richard said to me, “I see Nolini even more as a divine warrior than as a great thinker. He is Sri Aurobindo’s Earthly Shield and Heavenly Sword. His mind is illumined. I admire Nolini.”((( Extract from an interview by Chinmoy with Paul Richard dated 29 April 1967 at Flatbush, Brooklyn, New York. From the book ‘‘Nolini: Sri Aurobindo’s Unparalleled Friend – Son – Disciple” by Chinmoy.)))

NOLINI-DA — HIS ASHRAM LIFE

NIRODBARAN

It was about ten years ago that we assembled in this historic playground of hallowed memories on the occasion of the Mother’s passing and it was Pranab who addressed you at that time. Most unexpectedly it is on the occasion of another departure that we have assembled again tonight. It is the passing of Nolini-da who was, to borrow a happy phrase, one of the first and foremost disciples of the Mother, her collaborator and our eldest spiritual brother. The sanctity, solemnity and beauty of this occasion my poor words cannot express though my mind can envisage it without fathoming it. His “unhorizoned” consciousness is too wide for human measurement and it never ceased to climb towards the heights even when he fell ill. At that time I was once called at night. He said, “You see, I went out of my body and when I came back, the body received a jerk. Hence this minor disturbance. You will understand. I don’t need any medicine.” The tone was reminiscent of Sri Aurobindo. I had come to know that often Nolini-da used to go out of his body and had to keep his hold on somebody’s hand in order to keep contact with the earth. Once, he is said to have gone out to Bengal at the call of a dear friend of his young days. The friend was mortally ill and died. When Nolini-da brought back his soul to the Mother, she asked, “You have brought him to me?” It was a very perilous journey, indeed and he suffered much on the way. I had read also the Mother saying that he could easily go out of his body to the Sachchidananda state. Well, these superconscious things are beyond me; I know, a bit of the subconscious ones. Nevertheless I feel it my humble duty to present a few glimpses of his vast-visioned life to you so that you may have a rough idea of a person who rarely spoke of himself and to whom you may offer your gratitude and love for having quietly done so much for us. I must confess that most of what I shall say is based on my observation, reflection and conviction,

I had a moment’s sight of him when I met the Mother for the first time. She came to see me accompanied by Nolini-da, Amrita-da and Dilip-da. It was Dilip-da who had arranged the interview. Later, when I came to settle in the Ashram for good, I used to hear of three people’s names: Nolini-da, Amrita-da and Pavitra-da and of these three Nolini-da was an enigma, known to be a man of few words, and kept himself apart. People would not dare to assail his sanctum except on strict business. He was the secretary of the Ashram and was occupied with his own work but they all respected his aloofness. Often he used to be brusque with them and there were quite a number of anecdotes current in the Ashram about his abruptness. He had acquired the knack of upsetting people without himself getting upset. I shall quote two such stories. Once a sadhak complained to the Mother for what he considered Nolini-da’s rude behaviour to him. Sri Aurobindo wrote to Nolini-da about it. As a result he called the sadhak and apologised to him. On another occasion the hair-cutting saloon was to be opened. Nolini-da was approached to perform the ceremony; he flatly refused. The person wrote to the Mother and proposed another name, instead. When, next day, Nolini-da went to see the Mother, she asked him why he had refused. On coming down, he hastened to the saloon and opened it. There you can see two traits in his nature, the outer somewhat jerky and the inner obedient to the Mother, obedience being the first requisite of a disciple. Amrita who was his close associate used to say that Nolini-da was like уаṣṭi madhu. You have to chew it before you taste its sweetness. What a conversion took place in the later phase of his life! I marvelled at it. But let me not anticipate.

Though I kept myself at a distance because of his rudeness, his learning and writings had a great attraction for me. I admired and respected him for them as well as for his personality. His passion for knowledge, which made buying books his one hobby, could be summarised by a verse from Savitri “He sought for knowledge like a questing hound.” If the small can be compared with the great, I had also such a passion, but a minor one and I tried to satisfy it at Sri Aurobindo’s expense. You know the way I provoked, pestered, even bothered him with a host of questions. While I did this, Nolini-da gathered his consciousness in the ‘quiet’ cathedral of his mind and seated him on its high altar as the supreme deity. You know how Sri Aurobindo initiated him in the esoteric lores of the Vedas and Upanishads as well as in the secular knowledge of various literatures and languages. Sri Aurobindo’s heart must have been gladdened to find such a worthy young mind. Thus his approach to Sri Aurobindo was through the mind. I need not dwell at length upon this aspect, since his erudition is quite well known. Perhaps I can summarise it by quoting another expression from our Shastra. Both parā vidyā and aparā vidyā were at his command and they have all gone into 10 volumes of Bengali and 8 volumes of English works. They can make a side-stream running along with Sri Aurobindo’s vast Brahmaputra-like productions, fed and nourished by them and flowing into oneness with them. Sri Aurobindo has said that Nolini-da had a remarkable mind.

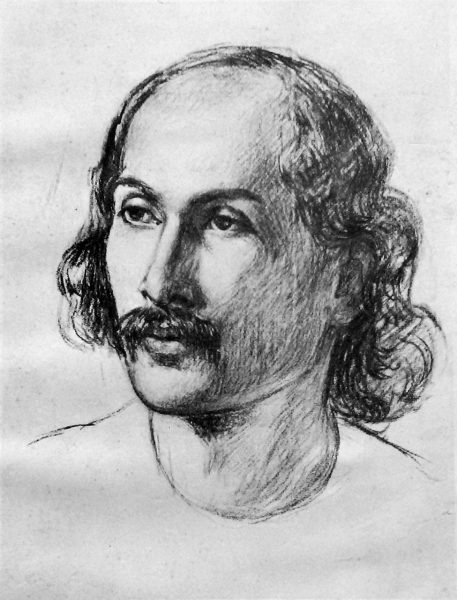

I have often wondered how he could contain such “infinite riches in a little room”. For except his broad and high forehead, the other parts of his body were frail. His forehead often made me think of Shakespeare and Einstein. In fact, at times during our medical visits in the morning when he had just come down from the inner empyrean as if with the gold dust of trance-land still on his body, a few locks of hair disarrayed, eyes dreamy, he looked very much like a mystical Einstein. But after he had had his wash, combed his hair and brushed his pet moustache, he was the elegant incarnation of Virgil who he had been in a previous life.

Still, he was by no means a book-worm, a recluse. He had his hands full. He had to manage the bulk of the Mother’s and Sri Aurobindo’s correspondence, distribute their letters to sadhaks and carry on other work as well as his voluminous writings. His domestic chores he did himself: washing his own clothes, making his bed, bringing his kuja-water, preparing his own tea, polishing his shoes, etc. He had a weakness for shoes. When Sri Aurobindo wanted to get rid of a pair of Vidyasagari shoes, having no further need for them, he said they could be given to Nolini since he was fond of shoes. He was a bit of a dandy. He was doing regular athletic exercises and taking part in competitions. Mass drill was his favourite item and he participated in it till his late seventies. With what gusto he practised the Mass drill which I found boring!

Every fraction of his life was disciplined and methodised. That is the external reason of his keeping fit and being capable of a huge output in a single life. I wonder if there is any world-figure today with so many facets combined and harmonised to such a degree of perfection. Indeed, he was a perfectionist.

But where is the key to be found for such various accomplishments? It was certainly in his inner development that lay the secret. He practised yoga with one-pointed concentration and took up his literary and other activities as a part of it. As in Sri Aurobindo’s own case, so in Nolini-da’s and in other cases of flowering in art, literature, etc. in the Ashram, Yoga and the Mother’s and Sri Aurobindo’s force were mainly responsible for success. It seems during the most brilliant period of the Ashram in 1927, when the Mother was bringing down the gods into the sadhaks, there descended into Nolini-da’s ādhāra the consciousness of Varuna, the Vedic god of Vastness. Hence the characteristic vastness in his writings. One could never achieve such an amplitude and integrality by mere mental labour. The work of the mere mind would be nothing but dry intellectuality. Besides, he must have attained a high degree of spiritual realisation to be able to contain that Vastness. Nolini-da’s later productions, like those of his Master, must have been written from a silent mind. I would say, transcribed rather than written. I would have doubted such a process, had not Sri Aurobindo convinced me of it by his personal examples and cogent arguments during our correspondence.

Now I enter a terra incognita. To talk of the inner developments of a Yogi is like a layman perorating on the theory of relativity. Fortunately I can draw upon some casual hints given by the Master and the Mother. Once when someone complained that Nolini-da was not doing Sri Aurobindo’s yoga since he kept aloof, was unsociable, etc., Sri Aurobindo replied, “If Nolini is not doing my yoga, who is doing it? Is sociableness, a part of yoga?” Secondly, when it was alleged that the sadhaks here would count for nothing in the world outside, Sri Aurobindo remarked, “The quality of sadhaks is so low?… There are at least half a dozen people here who live in the Brahmic consciousness….” This statement excited my curiosity and I surmised that Nolini-da must be one of these. I began to study his outer life. I could not get any clue except that he was absorbed in his own sadhana. Otherwise, he was a closed shell, would not expose his pearls to an outsider. Besides, I was just a novice and had not the ghost of an idea of what the Brahmic consciousness was. Apropos of my query I received another sweetly castigating letter from the Master.

None the wiser, I went on merrily without caring much about it, for Sri Aurobindo was my Brahman till he passed away. And then the Mother filled his place. In the ’sixties came a startling disclosure from the Mother. She wrote on Nolini-da’s birthday card — “Nolini en route towards the superman.” The years that followed brought a succession of revelations: “Nolini, with love and affection for a life of collaboration”… “For the prolonged continuation of this happy collaboration”… and lastly, in 1973, “With my love and blessings…for the transformation. Let us march ahead towards the Realisation.” These are very big words indeed. I don’t know if any other person received such high encomiums. I could now understand to some extent what these simple expressions meant and I was struck speechless. But Nolini-da swallowed all calmly and with ease. The coming superman did not ‘undermine’ the natural man. I could not glean his ample inner field. Perhaps he was marching ahead with the Mother and when there was “one more step to take and all would be sky and God,” the greatest calamity befell the earth. The Mother passed away. There was an overclouding gloom, dejection, consternation.

It was then that Nolini-da came forward and took the lead as it were. When the Mother’s body was brought down and laid in the Meditation Hall, the Trustees came and Nolini-da was called from his room. He was requested to say a few words. Keeping quiet for a moment, he stood up straight like a column of light and uttered in a commanding voice: “Let us stand together and go forward in harmony and collaboration. The Mother has said she will be with us in our consciousness.” He felt perhaps that a vacuum had been made and that he was called to do his part.

Now a new life began for Nolini-da and a new phase for us. He had to come out of his shell. All eyes turned to him for guidance, for help, spiritual and mundane. His guidance was said to be always precise and correct. He was invited to witness many functions; his approval was sought in many activities. In other words, he was called to shoulder a big part of the Mother’s spiritual work. A plethora of visitors asked for his touch. His writings were continuing in the same way and he used to read many of them in the School, in the Playground and in the Meditation Hall in front of his room. The idea, I believe, was to hold the Ashramites together and bathe them in the spiritual Presence. The Mother had assigned to him a French class for the elders and he continued it. In this manner, he was coming out more and more and his presence and nearness were available. It will not be an exaggeration to claim that he held the divisive tendencies together and saved us from falling apart. His hold particularly on the youth was of very good augury. When he had to undergo an operation for a cataract, the young boys kept vigil over him for about three months. Strange enough to observe that people operated upon along with him or afterwards got cured in two or three weeks while he took three months or so owing to a number of complications. He remarked jocularly that because he was given so much attention Nature took revenge.

In 1977, he had an apocalyptic vision of the Mother. He writes: “The Mother says, ‘Just see. Look at me. I am here come back in my new body — divine, transformed and glorious. And I am the same Mother, still human. Do not worry. Do not be concerned about your own self, your progress and realisation nor about others. I am here, look at me, gaze into me, enter into me wholly, merge into my being, lose yourself into my love, with your love; you will see all problems solved, everything done. Forget everything, forget the world. Remember me alone, be one with me, with my love.’ ”

After this vision probably he began to talk more and more about the Mother. To the departing students of the Higher Course he used to repeat that the Mother would be with them wherever they went. They were bound to her by a golden chain.

In 1978 either due to overstrain or some other reason he fell ill. Dr. Bose, Dr. Datta and myself formed a trio. I was the zero of the three, for my presence was more of a personal nature than a professional one. Now we enter the last phase of Nolini-da’s long career. It is a sweet song telling of sad things. His heart had gone wrong; to use Sri Aurobindo’s words, it was misbehaving. The blood pressure was high. The doctors succeeded in stabilising them. Satisfied with the progress Dr. Bose went to his home-town for about a month. After he had returned, there was a recrudescence of the symptoms and the condition took a serious turn. Consultation with an outside physician was thought of but Nolini-da had confidence in his doctors and vetoed the idea. However, things were becoming critical. Nolini-da himself said that he would be passing away. The Calcutta people were informed. Somehow the faith and energetic intervention of the doctors, particularly of Datta, called down the Mother’s Grace and Nolini-da was sent back from the threshold. A slow recovery followed and along with it he took up gradually his previous work, but naturally modified according to his measure. His movements were now confined to the Ashram precincts. Apart from the recording of Savitri, translating it into Bengali, seeing visitors and various other minor activities, most of the time he used to keep to his bed. We were visiting him as usual. At this time or even before, I do not remember, my stock shot up with him, though I was only a pulse-taking doctor. He used to call me by name, “Nirod”, which had an Aurobindonian ring, and, stretching his hand, ask me to feel his pulse. Often he used to do that and ask: “All right?” When all of us had examined him, his query was again: “All right?” “Yes, all right, Nolini-da,” we would answer and depart.

No superfluous talk. Sometimes he would simply give a steady look and then utter, “Bonne nuit.” From Datta he would inquire about his patients or he would himself speak of some patients who had approached him. Monique, the French Ballet teacher, had a very bad fracture and had to be sent to France. Nolini-da used to inquire about her almost three times a day.

After that massive attack he never enjoyed sound health and was kept on drugs which he used to swallow without any murmur. Anima his personal attendant would exclaim that she had not seen any other person taking 4 or 5 bitter drugs a day as if it was a habit. When the symptoms increased, I being near at hand was called at night and, if necessary, the others were informed. At times all the three medicos were present. In addition to his own troubles, occasionally Nolini-da used to groan in sleep as if in pain over the ailments of other people. Once he cried out repeatedly a person’s name. That person appeared to have been in a very critical condition that night and Nolini-da’s body received the vibration. The person’s condition turned for the better. There are numerous instances to show that he was sensitive to other people’s inner and outer condition and perhaps sent help to them in the yogic way. I know one case of an “incurable” malady cured or at least arrested by him. He had given peace and taken away deep sorrow from people. A woman came from London and wanted to have Nolini-da’s darshan. She was asked to take my permission. I saw her coming back from the darshan with tears streaming from her eyes. I wanted to know the reason. She said that when she had got up after pranam, she was flooded with light coming down upon her. She was permitted to do pranam to him every day from a distance. This was the first concrete proof I had of his spiritual communicative power and my solar plexus was knocked out. There was also a certain Bishop of good standing who visited the Ashram and met Nolini-da. He said that he felt a great power in him.

A few months before his passing, Dr. Bose suddenly passed away. Nolini-da was deeply moved. With tears in his eyes and a choked voice, he murmured: “What a fine soul! What a fine soul! He should not have gone before me.” He embraced his two weeping daughters when they came to see him. Such human expression of feeling from him was something new to us. Once Bose had seen in a dream Nolini-da’s upper body full of golden light; the lower part was absent. Nolini-da commented that it was an overmind vision. A few days later, as he was lying in his bed, I asked him through Anima where his consciousness could be. He answered: “Why, with the Mother!” I wanted more precision. Then he answered: “In the Overmind, in the cosmic consciousness.” I was simply swept off my feet. Though the Mother had indicated it, the information coming from Nolini-da himself had a tremendous effect upon me — I don’t know how people in general would understand the significance of that large utterance. Quietly I went away and tried to absorb the impact, for I knew more fully by that time what it meant and at once in a flash many of his actions or decisions which had puzzled us were revealed in a new light. He was suspected to have some weakness for his family. He replied: “Great souls are beyond such ties.” For the first time in our knowledge he had made a personal reference. We were also baffled by his tolerant attitude towards those who were known to do harm to the Ashram. When I saw him distributing his own photos to selected people, I was piqued. Now all these bizarre-looking movements troubled me no more and every question was set at rest. The mystery and mystique of all his actions became clear to me. Later I learned from Anima that Nolini-da had confided to her that he was mostly in the Overmind but at times a little beyond it.

To resume, yet cut our story short: Bose had gone from the doctor-group, two were now in harness, Datta being the head — I, a helper. Nolini-da was comparatively well and we expected that he would score his century. Anima and Matri Prasad, his two closest attendants, were regaling him with many stories and he too enjoying them. They were very free with him and would cut even personal jokes. I myself used to feel embarrassed at times; for this image of Nolini-da was a new development and I kept always my old attitude of respect towards him. In this period, which was a little before Bose’s departure, his most memorable action was to go and see Vasudha, a former personal attendant of the Mother, on her last birthday. We were somewhat alarmed. She had been bedridden. Nolini-da would often inquire about her and Datta kept him informed. I think Nolini-da had realised that Vasudha’s days were numbered. So he took this opportunity, though he could hardly walk even a few steps. We had great difficulty in putting him in a car and getting him just across the road. He sat before Vasudha with his chest heaving from exhaustion, took her hands into his own, blessed her and then came back.

His Bengali translation of Savitri had been completed and was expected to come out before his next birthday. Since the last months of 1983 things had begun to take a bad turn. His old pain in the heart re-appeared, stringent measures had to be taken regarding seeing visitors and other activities. His birthday on January 13 which had been expected to be a day of jubilation passed quietly, but he did not fail to meet the out-going students and give his blessings. Pain and distress were now on the increase. All modern measures were adopted, but only with momentary relief. Again the question of consulting a known heart-specialist was thought of, but met with disapproval. Distress and agony pervaded the general picture. We were at constant call and the attendants were ever vigilant, particularly at night. Less than a week before the last act, Nolini-da said to Anima that he would like to distribute his Savitri-translation to all the attendants. Books were a bit late in coming. He ordered: “Get the books quickly and call the people,” This was the last gesture. As Savitri was Sri Aurobindo’s last composition, its translation was Nolini-da’s last composition. And I can affirm that the masterly translation has added a large dimension to the Bengali language. When more than once doubts were raised about the exactness of some words, Nolini-da said with force: “One has to read the Vedas, Upanishads, Mahabharata, Sanskrit literature before questioning their use.” He surprised me by this unusual self-estimation.

On the 7th February the closing scene was enacted. We had examined him in the morning. The condition, though bad, was not critical. At noon, I heard that he had taken his usual meal and relieved himself. Datta was by his side. I was suddenly called at 4 p.m. and informed that after the motion Nolini-da had collapsed. When I came down, Datta said with a gloomy air that there was a sudden fall of blood pressure. Nolini-da had gone within; his eyes were shut; the pulse was thready and he was sweating profusely. The end was near. I sat by his side and called “Nolini-da!” He opened his eyes, gave a look of recognition as if from the Beyond and closed his eyes. Slowly, quietly, the breathing stopped at 4.42 p.m. — the grand finale of the long epic story.

Once I had collapsed due to a sudden fall of blood-pressure. Nolini-da was informed that I was passing away. He came to see me and found that I had revived. He seems to have remarked later that I couldn’t go away, I had still a lot of work to do. I suppose, one of the assignments was to help in his departure.

The day after the event, his body was laid out in the Meditation Hall. Hundreds saw his chiselled face embalmed in a Nirvanic peace.

The rest of the story is well-known. One thing to be observed is that his body was taken to the Cazanove garden in royal splendour. The procession of cars was something new in the history of Pondicherry. And almost the entire Ashram and a group of visitors made their pilgrimage to the burial place as a token of their love and respect. That too was something unprecedented in our experience. A man who had lived a quiet, unassuming life had earned the veneration of thousands. The body was laid to rest by the side of his old friends and colleagues Amrita-da and Pavitra-da, fulfilling his last wish. This was his only wish.

Now when I ruminate over what I was given to observe of the last phase of Nolini-da’s life, a few rare qualities remain impressed upon my memory and reveal to me his true soul. First, his freedom from the taint of personality: ego was dead. He had love for all and sundry. Enemy he had none, not even those who were considered to be doing harm to the Ashram. He accepted them all as the Mother’s children and left it to her to judge them. In consequence he gained universal respect and confidence. The government also had trust in him and the Prime Minister stated that he radiated peace.

Secondly, he always preserved a strong strain of impersonality even with those people who were close to him. That was his natural genius. This was a typically Aurobindonian stamp. The other Aurobindonian stamps were: he would not push himself to the front and never interfered with what people did, even when they happened to be his near ones, unless approached for advice. He never criticised anyone and did not approve of anyone making criticisms and using strong language. A large liberality, sweetness and compassion crowned all his actions and movements. Even children used to love him. If he did not approve of anyone’s actions, he did not confuse the man with his actions. He could invite the man to sit by his side.

These were the later manifestations of his hidden divine nature. Once somebody complained to him about life and its difficulties. He answered: “Why am I here?” Then the person who had complained said: “You are needed for the Ashram. Therefore the Mother has kept you here.” In a grave tone Nolini-da declared: “I am here for a particular development. So far in my evolution there was the sattwic consciousness: the element of knowledge. Now a new element has been added: love, ananda. For that new growth I am here. But no use saying all this. People won’t understand and they will distort it.”

Some of his last utterances are worth recording. I was once called at night and found him sitting on the edge of his bed. He said: “You see, this body is of the earth earthy and will mix with the earth. But the realisation will remain.” Then in the last days he used to be in-drawn. We thought he was sleeping. When he came out of his absorption he had the appearance of an ever-joyous child and he also spoke and behaved like one. I said: “Perhaps you are in the Sachchidananda state” — to which he replied with a smile: “It is in an Anandamaya region.” On another occasion he was heard to mumble in an absorbed way: “Sat-yogi, Sat-yogi.” Asked whether he was by any chance referring to himself, he softly whispered: “Yes.” After that he withdrew almost wholly into himself and, when he spoke, it was to tell many that he would be leaving his body. On his 95th birthday he remarked: “This new year will be very critical for me.” When he was once asked where he would be after he had left his body he stated very clearly: “A little beyond the Overmind.” During those days he had also visions of the three goddesses Chamunda, Kali and Gauri. About Chamunda, he said that she was trying to do mischief with his heart and he had detected it. Kali was all dark: everywhere there was darkness. In another vision he saw that he had gone away to a solitary place, all alone: there was no sign of life anywhere around. Then he saw Matri, following him.

When I try to assess his contribution to the sum-total of the Mother’s and Sri Aurobindo’s work, I feel that short of the Supermind he realised in himself a true synthesis of Sri Aurobindo’s Yoga and proved that this many-sided, complex, comprehensive Yoga is not an insane chimera. Further, he has made the path easier and smoother for posterity, as he has himself said that his realisation will remain. He serves as a bridge, an intermediary between us and the Mother. I can illustrate this point by citing the experience of a young sadhika the very night Nolini-da passed away. She went home with a heavy heart after seeing Nolini-da. She read a few pages from The Yoga of Sri Aurobindo before going to sleep. She dreamt that Nolini-da’s body had been shifted beside the Mother’s room on the second floor. People were going to see him in batches. When she arrived, she saw Nolini-da standing at the door radiant, youthful and full of zest. He called her in and cried loudly: “Come, come, today is my Bonne Fete.” Then he made her sit down and talked a lot on the Mother and Sri Aurobindo. Simultaneously she saw his dead body lying beside the wall, as it had been in his room. She was very much astonished. Then she read a chit from Counouma, asking her to go to Cazanove, since she was one of the attendants, and a vehicle had been arranged for the purpose.

As in life, so in after life his was a totally dedicated and one-pointed luminous soul come down to serve the Divine Mother and Sri Aurobindo. Not that he had no difficulties. He had plenty of them and had to fight a hard battle. But what saved him, he said, was his completely frank confession of them to the Mother.

Let us try, therefore, to be Nolini-like, to quote K. D. Sethna, if the Mother and the Master seem far beyond our reach.

Finally, my, story will be incomplete if I fail to recognise the inestimable service rendered by our young people to Nolini-da. We cannot be too grateful to them for what they have done night after night, specially Anima and Matri. Anima’s devotion and self-abnegation will be a matter of history. For years she looked after Nolini-da — his secretary, nurse, mother, sister, all in one. As soon as he called “Anima”, she was there. She gave him all the royal comfort and ease he deserved. She may have her faults — who is free? — but, without her, Nolini-da would have left us long ago and in a very lamentable condition. Our admiration for her knew no bounds. She kept her eyes upon the comfort of the attendants as well. She was full of life and cheer and had a fund of tales, anecdotes, reminiscences by which she tried to enliven Nolini-da’s mood and mitigate his physical distress though she herself had high blood-pressure and was subject to headaches, pains and other ailments.

In conclusion let us hear a part of the recorded voice of Nolini-da where we get a clue to his true being (svarūpa):

“The story is after all the story of our adventure upon earth, a common adventure through centuries — not only through centuries but perhaps from the very creation of the earth. It is the story of the adventure of a group of souls, souls who were destined, who were created for the advent of a new creation. I will speak of only just a few bits and some important episodes of this adventure in which I participated, because you wanted to hear my life.

“We came, all of you, all of us who are here, most of them, in different epochs at the crucial stages of our evolution. In different periods, whenever there was a necessity of an upliftment or an enlightenment, we all came together, each in his own way. So one or two episodes like that I can tell. For example, in Europe a crucial turning-point of its history was the Renaissance, the new light. At the time of the Renaissance we all know that the creator of the Renaissance was Sri Aurobindo — Leonardo — and the whole Renaissance was in his consciousness and all those who flocked around him, each one did his own work. You know that Amrita was intimately connected with that work — he was Michael Angelo. And Moni was there — Suresh Chakravarty. He was one of the chief artists. I have forgotten his name…

“But all…the work they actually did, you know, the important thing, the consciousness they brought — expressed some sad event, some not so, but living, concretising the consciousness….

My contribution in that age of Renaissance was in France. The Mother always said: “Your French incarnation was very prominent, even today it is very prominent.” That little bit of evolution is still living. The consciousness at that time in France — that was also the beginning of the Renaissance and… the new creation, new poetry — I was a poet of that time and introduced the new poetry in France. At that time the King of France was François Ier. He was in the political — also in the general life of the people he introduced this new light, new manner of consciousness. So I was with him. And who was François Premier you know — Duraiswamy!

“The consciousness of the reality of that country was so strong that when I started reading or writing French — I wrote French — then sometimes I noted down some lines… later I found that I had noted down exactly some verses of this poet of France, Ronsard…”

I may add an incident of recollection by Nolini-da of a past life. One day when he went to inspect our School garden, he was very much interested in observing the plan of the garden, the trees, the lotus pond and he remarked: “I was the gardener of Louis XIV, Le Nôtre.”

N.B. Nolinida’s last act of wisdom which we came to know after his departure was the selection of a competent young sadhak as a Trustee of the Ashram in his place. The selection and the way it was done was really a master-stroke.

SRI NOLINI KANTA GUPTA

(A Life Sketch)

STEPHEN K. WATSON

As observed by Sri Aurobindo, the life of a man of destiny is not on the surface for the outer vision of man to perceive. This Truth was confirmed in the long, dynamic life of Sri Nolini Kanta Gupta, as it flowed river-like, seeking its way to the Ocean of the nectarous Divine Reality. The very source of his life’s dynamism and creativity was the Ocean of Consciousness in which it moved through his daily actions. Some glimpses of the inner and outer movement of his life are found in his own Reminiscences, from which much of this brief life sketch draws its truer colours. Thus, it is hoped to avoid distortion in this delineation of a man, much of whose outer life was an outflowing of a vast inner Truth, inaccessible to man’s limited gaze.

Sri Nolini Kanta Gupta, who was born in Faridpore, Bengal (now located in Bangladesh), on 13 January 1889, was the eldest of a family of six brothers and two sisters. At the age of three years, he came to Nilphamari, where his early education began. That he describes his penchant for learning in tandem with his mastery of physical activity, in the form of sports, is highly significant, as his life unfolds itself as one destined to collaborate in a work in which the highest mental and spiritual development joins with a simultaneous effort for physical perfection. As he recalled his earliest life’s occupations:

“I have dabbled in football almost since my birth or, to be more exact, from the time I barely completed five. My hand was introduced to the pen or chalk and my feet touched the ball practically at one and the same time. Would you believe it, I had my formal initiation into studies not once but twice, and on both occasions it was performed with due ceremony on a Saraswati Puja day, as has been the custom with us. The first time it took place, when I was only four years old and I cannot now tell you why it had to be at that early age. It may be that I had gone into tantrums on seeing somebody else’s initiation and a mock ceremony had to be gone through just in order to keep me quiet. But I had to go through the ceremony once again at the age of five, for according to the scriptures one cannot be properly initiated at the age of four, so the earlier one had to be treated as cancelled and a fresh initiation given to make it truly valid. Perhaps this double process has had something to do with the solid base and the maturity of the learning!”((( Nolini Kanta Gupta, ‘Reminiscences’, Collected Works of Nolini Kanta Gupta, Vol. 7, (Pondicherry; Sri Aurobindo International Centre of Education, 1978), p. 445.)))

We discover this happy union of the inner and the outer, the spiritual-mental and the physical, at each phase of the development of one who was destined to play a role in the spiritual work of the great reconciler, Sri Aurobindo.

Nolini-da V high school education began in 1904 at Rungpore, where his sensitive mind and heart were first touched by patriotic influences. Between the age of 15 to 18 years, he went to Calcutta for his higher education at the Presidency College. His patriotic urge for the liberation of his Motherland was further enkindled during his college experience. During his holidays at Rungpore, he had his first fearless, one might even say defiant, brush with the government of the British colonialists. As he explained:

“During the holidays I was back in my home town of Rungpore….We roamed the streets singing, that is shouting hoarsely at the top of our voices. We did morning rounds with songs like

‘Awake О men of India, how long would you sleep’ and so on….I roamed the streets as usual, shouting ‘Bande Mataram’ with the processions….”(((Ibid., p. 325.)))

As the Government had served an order banning all processions in the town, Nolini-da, at the age of 16 or 17, was brought to the court for his deliberate defiance of the law. Fined Rs. 25, in those days quite a sum, he was thus initiated into the movement for the freedom of India, which was to bring him into contact with the one destined to mould his mind and life, his Guru in both laukika and parā vidyās, Sri Aurobindo.

He had the first darshan of the one to whom he was to surrender his all sometime when he was not yet 18 years old. Of this college experience he wrote:

“…. I myself attended a number of meetings, particularly at Hedua, in Panti’s Math and College Square, in the evening after college hours…. I chanced to see, in the fading light of evening at a meeting in College Square, Sri Aurobindo. He was wrapped in a shawl from head to foot — perhaps he was slightly ill. He spoke in soft tones, but every word he uttered came out distinct and firm. The huge audience stood motionless under the evening sky listening with rapt attention in pin-drop silence…. And the other thing I remember was the sweet musical rhythm that graced the entire speech. This was the first time I saw him with my own eyes and heard him.”((( Ibid., p. 323.)))

Though Nolini-da attended the Presidency College along with many who were to make great names for themselves, as the flame of patriotic fervour for the freedom of India grew in his breast, the interest in merely academic pursuits began to pale.

While Nolini-da was a student at Presidency College, Lord Curzon, then Viceroy of India, divided Bengal, which ignited the flame of protest all over the State. At this time Nolini-da adopted a subtle form of protest, in contrast to his earlier experience in Rungpore. He explained:

“In what manner did I register my protest? I went to College dressed as if there had been a death in my family, that is to say, without shoes or shirt and with only a chadder on….”1)

Perhaps during this period, the contentment with an ordinary sort of life also died a natural death. As he expressed it:

“….Within a short while I discovered that my mind had taken a completely different turn. Studies offered no longer any attraction, nor did the ordinary life of the world. To serve the country, to become a devoted child of the Mother, for ever and a day, this was now the only objective, the one endeavour…. And as to my decision, that would be unshaken, ‘as long as shone a sun and a moon. yavaccandra-divakarau .…”((( Ibid., pp. 328-29.)))

This brings us to the next phase in the life of Nolini-da, in which the freedom of the Motherland became the all-consuming passion. He opted to follow the path of Kurukshetra, armed struggle against the English. This was pursued through the manufacture of bombs at the Manicktolla Gardens in Muraripukur. He explained:

At last I made up my mind finally to take the plunge, that I must now join the Manicktolla Gardens in Muraripukur. That meant goodbye to College, goodbye to the ordinary life…. This decision to choose my path came while I was in my fourth year…. It was settled that I would join the Gardens and stay there…. I attended College as well, but at infrequent intervals. College studies could no longer interest me.”((( Ibid., pp. 337-38.)))

This radical choice in Nolini-da’s life was much more than a mere ‘cult of the bomb’. His life was infused with a spiritual aspiration which welded his being with the spirit of sacrifice for the freedom of India from British domination. Here again, we observe the dual elements of pragmatic means to a physical realisation of freedom, as well as a strong element of spiritual means to spiritual freedom, to be won through tapasyā and sādhanā. Manicktolla Gardens was not a mere den of terrorists, but had, side by side with bomb-making, an atmosphere of intense spiritual seeking. It followed much the spirit of the Bhagavadgita, in which the highest spiritual Truth was revealed on the battle field. At the same time, Nolini-da’s seeking for intellectual learning was evident. As he explains:

“… life at the Gardens… had just begun…. We began with readings from the Gita and this became almost a fixed routine where everybody took part.

About this time, I had been several times to my home town of Rungpore…. At the Rungpore Library I came across another book, namely Gibbon’s famous Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire… and added a great deal to my learning and knowledge….”((( Ibid., Vol. 7, p. 340.)))

Life in the Gardens was pervaded by the joy and enthusiasm of the inmates. Further describing the character of the atmosphere in the Manicktolla Gardens, Nolini-da wrote:

“Although we had made the preparation of bombs our first object when we chose this lonely and out of the way place, we were not… atheistic and given wholly to a materialistic philosophy. It had been a part of our plan to devote some time to the cultivation of an inner life too in that solitude. I remember how we would get up an hour before sunrise and sitting down in that calm atmosphere in a meditative pose we would recite aloud with deep fervour and joy the mantra of the Upanishad:

‘…. As one gets oil out of oilseeds, as one gets butter out of curds, as one gets water out of the stream, as one gets fire out of wood, even so one seizes the self out of the self, one who pursues it in truth and tapasyā….’

It would not have been far out to call it an Ashram…. And it was precisely because of this that Barin got Lele Maharaj down here for our initiation and training in Sadhana, the discipline of Yoga, the same Lele who had been of a particular help to Sri Aurobindo at a certain stage of his own sadhana….”((( Nolini Kanta Gupta, Reminiscences, p. 27.)))

Yet destiny had already chosen for Sri Nolini Kanta the Guide who would show him the way to join the heights and depths of his being in a perpetual flow of Light. The one whom he had seen speaking to the crowd in College Square, Sri Aurobindo, was to meet him soon, when Barin, Sri Aurobindo’s brother, sent Nolini-da to Calcutta to request him to visit the Gardens. The truth that when the aspirant is ready the Divine appears to him in the form of the Guru, is clearly discerned in the relation of Nolini-da with Sri Aurobindo. As Nolini-da describes their first meeting:

“…. It was during my stay at the Gardens that I had my first meeting and interview with Sri Aurobindo… it was about four in the afternoon when I reached there((( The house of Raja Subodh Mullick near Wellington Square.))) …. As I sat waiting in one of the rooms downstairs, Sri Aurobindo came down, stood near me and gave me an inquiring look. I said, in Bengali, ‘Barin has sent me. Would it be possible for you to come to the Gardens with me now?’ He answered very slowly, pausing on each syllable separately — it seemed he had not yet got used to speaking in Bengali — and said, ‘Go and tell Barin, I have not yet had my lunch. It will not be possible to go today.’ So that was that. I did not say a word, did my namaskāra and came away. This was my first happy meeting with him, my first Darshan and interview.”((( Ibid., Collected Works. Vol. 7, p. 347.)))

The pursuit of the path of violence was not to succeed. The members very early experienced the inevitable with the accidental death of Prafulla((( Suresh Chakravarty’s elder brother, and Nolini-da’s very intimate friend.))) during their first experiment with a bomb. Still, they were firmly determined to sacrifice life itself for the cause of India’s freedom. As Nolini-da described their bhāva:

“…. We were no Vaishnava devotees. We were Tantriks, worshippers of Kali. Our chosen deity was the Goddess of Death incarnate, with her garland of skulls. Ours was the heroes’ worship of strength.”((( Ibid., p. 350.)))

In this happy, nomadic existence at the Gardens, we observe a mingling of several strands of experience which may seem to many incompatible. Along with the Vedantic seeking of the Upanishads, and the surrender to the terrible Mother of Tantra, Nolini-da simultaneously continued to enrich his mind. As he explained:

“… However, we did not confine our studies to religious books alone, we had with us some secular literature as well. It was precisely at this period that a collection of Mathew Arnold’s poems came into my hands. The book belonged to Sri Aurobindo…. That was my first introduction to Matthew Arnold….”((( Ibid., pp. 350-51.)))

Thus, spiritual seeking was not sought at the cost of the development of the mental faculties, nor to the detriment of their sacred duty to battle for the freedom from domination of the Indian people. Yet the Supreme Mother had other plans for the progress of Her intended manifestation. Thus the life at Manicktola Gardens was brought to an abrupt end. At the age of 18 years, Nolini-da was arrested with the other members of the Gardens. He writes:

“… We were all arrested in a body. The police made us stand in a line under the strict watch of an armed guard. They kept us standing the whole day with hardly anything to eat…. We were taken to the lockup at the Lai Bazar Police Station. There they kept us for nearly two days and nights. This was perhaps the most taxing time of all. We had no bath, no food, not even a wink of sleep. The whole lot of us were herded together like beasts and shut up in a cell…. Then, after having been through all this, we were taken to Alipore Jail one evening. There we were received with great kindness and courtesy by the gentleman in charge…. And he had us served immediately with hot cooked rice. This was our first meal in three days, and it tasted so nice and sweet that we felt as if we were in heaven.”((( Ibid., p. 364.)))

Still, the ordeal was just beginning. As undertrials they passed one year in jail. Sri Aurobindo was amongst them. Charged with sedition and waging war against the King, the possibility of death hung over their heads, before they could really begin their underground fight for India’s freedom. As with Sri Aurobindo, so also with Nolini-da, this enforced retirement from the field of action brought to the fore the always-present current of spirituality, which would more and more guide their external actions. Still, at such a tender age, Nolini-da had to struggle with the negative emotions of despair and despondency, which he victoriously tackled with the help of the dynamic spiritual power of a book that came into his hands. He writes:

“A personal reminiscence. A young man in prison, accused of conspiracy and waging war against the British Empire. If convicted he might have to suffer the extreme penalty, at least, transportation to the Andamans. The case is dragging on for long months. And the young man is in a solitary cell. He cannot always keep up his spirits high. Moments of sadness and gloom and despair come and almost overwhelm him. Who was there to console and cheer him up? Vivekananda. Vivekananda’s speeches. From Colombo to Almora, came, as a godsend, into the hands of the young man. Invariably, when the period of despondency came he used to open the book, read a few pages, read them over again, and the cloud was there no longer. Instead there was hope and courage and faith and future and light and air….”((( Ibid., Collected Works. Vol. 2 (Pondicherry: SAICE, 1971), pp. 103-4.))) Indeed, it was the soul that Vivekananda could awaken and stir in you.

During that period, in another cell, Sri Aurobindo was rapidly unfolding his spiritual Being and Power, which in time would act more and more on the being of Sri Nolini Kanta Gupta. Finally, on 6 May, 1909, Sri Aurobindo was released. No evidence had been found of his involvement in terrorist activities. Nolini-da also was released.

Upon coming out of jail, Nolini-da was in a fix as to his next step in life. For him, going back to the ordinary life was out of the question. He writes:

“….I had just come out of jail. What was I to do next? Go back to the ordinary life, read as before in college, pass examinations, get a job? But all that was now out of the question. I prayed that such things be erased from the tablet of my fate, śirasi mā likha, mā likha, mā likha…. One day, I felt a sudden inspiration. It had to be on that very day: on that very day I must renounce the world, make the Great Departure, there was to be no return….”((( Ibid., Collected Works. Vol. 7, p. 383.)))

External renunciation, however, was not to be the destiny of Nolini-da, who was to demonstrate by example the ideal of spiritual transformation within the activities of life. Having been frustrated in his first attempt to renounce the world, he found his niche soon in his daily afternoon visits to Sri Aurobindo, at the Sanjivani office in the residence of his [Sri Aurobindo’s] uncle. The impulse to something higher than the ordinary round of life was still present, and surfaced soon after, along with an impulse to see all of India as a wandering ascetic. This time Sri Aurobindo interfered by asking him to wait a few days, and inviting to travel with him for some political work in Assam. The desire was to surface a third and last time in Pondicherry, before the Mother’s final arrival. Nolini-da sums up this movement in his life as follows:

“The first time it had been myself, my own self or soul, who rejected sannyasa. The second time the veto was pronounced by the Supreme Soul, the Lord — Sri Aurobindo himself. And the third time it was the Supreme Prakriti, the Universal Mother who it seems scented the danger and hastened as if personally to intervene and bar that way of escape for ever, by piling up against us the heaven-kissing thorny hedge of wedlock….”((( Ibid., p. 390.)))

Though not recognized as yet, Sri Aurobindo’s ideal of the Highest Spirit manifest in Life was to become Sri Nolini Kanta’s guiding Light. Next Sri Aurobindo initiated him into several new experiences of life. Though he had never written anything beyond college papers and essays, Sri Aurobindo asked him to pick out some important items from the English papers and write them up in Bengali. As Nolini-da recalled:

“… He seemed to be pleased on seeing my writing and said that it might do. He gave me the task of editing the news columns of his Bengali paper Dharma ….”((( Ibid., p. 394.)))

Thus the job of editing the news columns of the Bengali paper fell to his lot, which slowly turned him into a journalist. It was also from the Hands of Sri Aurobindo that he was to receive earned money for the first time. Though this earning for his editorial work was only a token amount, it is interesting that his first writing was done for his destined Guru and his first earnings came from him as well. The die was being cast for a lifelong association in union with one who led his inner and outer life to its full blossoming.

From that time he came to stay at Shyampukur, living and working on the premises of the two papers, Dharma and Karmayogin. Here, his true awakening and education began in earnest under the benign influence of the Master. As he noted:

“It is here that began our true education, and perhaps, nay, certainly, our initiation too…. Sri Aurobindo had his own novel method of education…. It went simply and naturally along lines that seemed to do without rules. The student did not realise that he was being educated at all… By giving me that work of editing the news he made me slowly grow into a journalist underwriter. Next there came to me naturally an urge to write articles. Sri Aurobindo was pleased with the first Bengali article I wrote…. This my first article was published in the 11th issue of ‘Dharma’ dated 15th November, 1909. I was twenty then. Some of my other articles came out in ‘Dharma’ afterwards. My writings in English began much later…. One day in the midst of all this, Sri Aurobindo asked me all of a sudden if I had any desire to learn languages — any of the European languages, French for example. I was a little Surprised at the question, for I had not observed in me any such ambition or inclination. Nonetheless I replied that I would like to. That is how I began my French….”((( Sisir Kumar Mitra, ‘Nolini Kanta: Towards the Heights‘, “Srinvantu”, November 1969, p. 146.)))

How much Sri Aurobindo’s initiation was fruitful became obvious many years later, when the Mother of Sri Aurobindo Ashram, a native of France, observed about Nolini-da:

“He is no inconsiderable poet in French.”((( Ibid.)))

The life of mental and spiritual enrichment, side by side with continued writing to spur the Independence Movement, was brought again to an abrupt halt one evening, when a friend, Ramchandra, brought the disturbing news that the Government had again decided to arrest Sri Aurobindo. As Nolini-da recalled, Sri Aurobindo

“…. came out of the house and made straight for the riverside…. Those of us who were left behind continued to run the two papers for some time…. But afterwards, we too found it impossible to carry on and our pleasant home had to be broken up. For news came that the police were after our blood;… And I decided to leave for an obscure little village in distant Barisal…. I spent a couple of months there…. Then I got the news that the time had come for starting on my travels again….”((( Ibid., Collected Works. Vol. 7, p. 397.)))

Thus Nolini-da followed the footsteps of Sri Aurobindo to Pondicherry, where at last the foundation would be laid for an undisturbed unfoldment of a great spiritual endeavour. The earliest days at Pondicherry were characterised by an austere simplicity. As Nolini-da recalled:

“…. I may add that we had no such thing as a bed either for our use. Each of us possessed a mat, coverlet and pillow; this was all our furniture. And mosquito curtains? That was a luxury we could not even dream of…. for Sri Aurobindo we had somehow managed a chair and a table and a camp cot. We lived a real camp life…. All I can recall is a single candle stick for the personal use of Sri Aurobindo. Whatever conversations or discussions we had after nightfall had to be in the dark; for the most part we practised silence….”((( Ibid., pp. 417-8.))).

Sri Aurobindo continued to lead his companions in serious study of various subjects. For several months, for about an hour every evening, the topic of study was the Veda, which drew the special interest of Nolini-da, as well as Subramanya Bharati, the famous Tamil Poet. Sri Aurobindo continued to initiate Nolini-da in the study and mastery of various languages. Nolini-da noted:

“…. Sri Aurobindo has taught me a number of languages…. When I took up Greek, I began straightaway with Euripides’ Medea…. I began my Latin with Virgil’s Aeneid, and Italian with Dante. I have already told you about my French, there I started with Molière….”((( Ibid., p. 421.)))

Thus was Nolini-da’s mind moulded carefully by Sri Aurobindo, from his twentieth to twenty-fifth year. A characteristic of Nolini-da was his continued pursuit of football, side by side with his intellectual enrichment. At the age of 25, in 1914, Nolini-da went back to Calcutta. He returned to Pondicherry and remained for several years before going again to Calcutta. This time, in 1919, he went to Nilphamari, where, at the age of 30, he married Indulekha Devi of Mymensingh. He continued to travel between Pondicherry and Calcutta for several years, having begun publishing his Bengali writings in 1921. He brought his wife with him once to Pondicherry, but thereafter he came alone. Ultimately his outer travels ceased, with the unfolding of the imperative spiritual urge of his soul, not a little influenced by the arrival of the Mother. It was perhaps the Mother who awakened him to the spiritual stature of his Companion, Sri Aurobindo. As he explained:

“The Mother came and installed Sri Aurobindo on his high Pedestal of Master and Lord of Yoga…. the Mother taught by her manner and speech and showed us in actual practice, what was the meaning of disciple and master….”((( Ibid., p. 422.)))

It was, further, at the urging of the Mother that Sri Nolini Kanta’s trips to Calcutta ceased. After the Siddhi of Sri Aurobindo, Nolini-da’s place in his spiritual work was settled. From 1926, Nolini-da never again left the Ashram in Pondicherry, where he served as its Secretary and later as one of its Trustees.

From this period on, it is difficult to say much about Nolini-da’s life. Outwardly, he worked for Sri Aurobindo’s Ashram and also continued to publish writings in Bengali, English and French. He engaged himself in sports activities throughout his life, even into his eighties. His writings have attracted many by the light they throw on many facets of knowledge and life, including luminous expositions of Sri Aurobindo’s Yoga. This dynamic light of an ever-expanding spiritual awareness was applied by Nolini-da to many aspects of mind, life and matter. From his writings alone it becomes clear that their extreme variety and depth of insight are explained as the result of his being an instrument in the ‘hands’ of a supreme Light, which is capable of illumining everything upon which it is directed. His writings are all short, yet they carry so much light and power that one’s understanding is immediately kindled. One finds them containing many germinal ideas, each capable of serving as the basis for a comprehensive understanding of the multiple facets of existence. In his English works alone, one finds political theory, international relations, poetry, musical theory, ancient and modern Western and Eastern literature, esoteric Yogic knowledge, and his own poetry. All are critiqued in such a way as to open windows onto the spiritual Reality behind, of which they are manifestations. In his Bengali writings, he treated all of the above subjects, and translated as well much of the best from Western Poetry. His poems in French were even appreciated by the celebrated French Poets, Mon. Maurice Magre and Sylvan Levi. This list does not exhaust the subjects masterfully dealt with in Nolini-da’s writings. His last work in Bengali was his translation of Sri Aurobindo’s epic poem Savitri. By a thorough review of his collected writings, one clearly understands the Upanishadic reference to that knowledge, “knowing which, everything is known.” It is such knowledge, in dynamic and creative form and power, which was manifest in Sri Nolini Kanta Gupta. Thus it was demonstrated by his life and action that the highest spiritual realisation is not only compatible with life and the world, but productive of the means to fully understand and enjoy the world in perfect consonance with the Supreme Truth. We see in Nolini-da the Light and Power of the Supreme Mother, pouring itself out upon the world of Her Creation. Such truly is the ideal of Sri Aurobindo, as demonstrated in the life of his lifetime companion and disciple, Sri Nolini Kanta Gupta. He published about 50 Bengali works, and his English writings are embodied in Eight Volumes of his Collected Works. Yet his prodigious outpouring in the form of writings is only one aspect of his life from 1926 to 1983. The crucial development of his spiritual realisation during this period is what really gives the immense value to his writings. About this spiritual achievement, his Yoga Siddhi, we must refrain from any assessment, due to our limited capacity to know. We can perhaps only discern the trend of his spiritual life from the words of Sri Aurobindo, who told Nirodbaran sometime in 1940:

“I always see the Light descending into Nolini.”((( Sisir Kumar Mitra, ‘Nolini Kanta: Towards the Heights’, “Srinvantu”, Calcutta, November 1969, p. 147.)))

We can safely say that his Realisation in Sri Aurobindo’s Integral Yoga far transcends even his tremendous outer activity in the form of his published works. The Mother’s words to him on his birthday reveal something of this aspect of his True Life. On 13 January 1967(?), the Mother blessed Nolini-da on his birthday in the following words:

“Happy Birthday Nolini en route towards the Superman. With my love and affection and blessings.”((( V. Madhusudan Reddy, ‘Nolini, Arjuna of our age, Hyderabad: Institute of Human Study, 1979, p. 68.)))

Again, on 13 January, 1971, the Mother sent Her birthday Blessings, writing.

“Happy Birthday Nolini with my love and affection for a life of collaboration and my blessings for the prolonged continuation of this happy collaboration in peace and love.

The Mother”((( Ibid., p. 69.)))

We can confirm our perception that he continued to march ahead tirelessly towards greater realisation, and served as a luminous example of an instrument of the Truth-realisation of the Integral Yoga of Sri Aurobindo. His heights and depths were, however, not measureable by us. The testimony of many who had his darshan, however, could confirm the perception which was expressed one day by Andre, the Mother’s son, when he visited Nolini-da after the withdrawal of The Mother. He spontaneously told him that to come to him is truly to be in the Presence of the Mother.

One aspect of the Mother which was quite apparently manifest in the life of Nolini-da, Mahasaraswati, also made itself felt at the end of his physical life. Sri Nolini Kanta left his body on the auspicious day of Saraswati Puja in 1983. The room from which he served the Mother and the Master, and achieved his spiritual realisation over a period of more than fifty years, still retains the glow, unmistakable of the Divine Presence with which he united his being. The body with which he served the Supreme Divine continues to radiate the penetrating Peace of Divinity from his Samadhi at Cazanove. Even in apparent death, the body he left behind continues to manifest the Divine Vibrations, thus testifying to the Truth of the Integral Ideal of The Yoga of his Master, Sri Aurobindo.

NOLINI-DA

ANIMA

Know him?

Dawn-to-dusk

Dusk-to-dawn

Whirls the Sun’s cyclic way —

How much is he seen?

Yet he is there.

Air-space is there,

Pervading everywhere —

Upholder of all living things,

Self-existent is its being.

Who remembers? How much of it?

Filling the universe, the creation

Ceaseless the light particles

Shower non-stop.

Who cares to remember them?

Moon-phases increase and decrease,

In the sight of the world’s measure

They are seen waning and waxing —

Yet the moon stays ever full

Beyond the ken of man.

In the yard on a sleepy midnight

I stand, a sweet zephyr blowing,

Silent in the night,

Steeped in the honey-sap of noiselessness,

Do I remember?

In the blaze of a fierce midday,

In the breast of an empty expanse

I plunge in the cool of the lake

Where an icy touch spreads over the body

Snuffing out the midday fire,

The robe of torrid days falls

Like a discarded mantle —

Peace descends —

In the night’s profound silence

The city is merged

In slumber deep,

Have you seen it from the roof-tops?

The Post-runner in the distance passes

Bearing alone the words of the dawn,

His bells ringing as soft music

Have you heard?

At the village outskirt towers the huge

Aswattha wrapt in meditation —

A hermit below has his hut,

Above in the foliage the vultures nest,

Yet the Aswattha in affection guards

Both equally —

A lonely coconut tree stands apart

Braving storms. The scorching sun

Leaves it unmoved, ever mounting high

To one goal, the lofty sky —

Why? Who knows?

In childhood roaming, holding father’s hand

I stretch out to feel the water’s silken touch,

In his eyes saw you his affection’s indulgence?

In winter’s drowsy night, the mother’s warm hug —

Do you remember?

All of this and more

Have I seen and got

In his closeness, yet I saw not

Nor got ever so much more.

Yet I know all this

Is nothing — his lustre only,

He remains, overflowing and beyond all,

Otherwhere, alone, unique

In his own self-form beyond,

Unknown to the mind and its speech.

He alone soul-companion, yet

Hard to discern, no word explains —

Still how easy to love him —

To plunge into his bosom confident, fearless,

Staring into the bottomless effulgence of his

Star-like eyes — how easy to give in Silence.

(Translated by Kalyan from her Bengali Book of Poems — Manjira)

THE INTEGRAL YOGA AND NOLINI KANTA

ARABINDA BASU

Sri Aurobindo has introduced to spiritual seekers a new Yoga — the Integral Yoga. Its integrality consists in the novelty and totality of its aim. He is emphatically clear that the primary and ultimate purpose of yoga is to realize the Divine. In his experience of the supreme Reality, the Divine Being has many aspects. The integral Yoga aims at realizing all the aspects in one comprehensive experience. It is not being suggested that a practitioner of the integral yoga can have this experience all at once. He cannot do so because the medium of knowing the Reality that has been utilized for the purpose till now is not capable of achieving the aim of the integral yoga. This is why Sri Aurobindo insists that a new level of consciousness must evolve in spiritual seekers which will enable them to have the integral knowledge of the Divine. But before this new level of consciousness can be evolved, says Sri Aurobindo, the Reality has to be realized by the means that is at the disposal of a seeker now:

Man is a mental being. Even in his spiritual quest mental consciousness is his means of progress towards the goal. Mental consciousness purified, made calm and tranquil and receptive of the Light, of the Being-Consciousness-Bliss Reality, of God, becomes capable of reflecting that Light. The reflection can be so clear that it almost seems that it is not a reflection but the reflected Reality. This is what passes as knowledge of the Self, experience of God, realization of the Absolute etc. But if we look at the history of spiritual mysticism, it will be easily seen that the experiences described as those of Self, God, Absolute are very different and diverse. It will be wrong to say that the experiences are not genuine. But it will also be right to say that they are partial. There is, however, according to Sri Aurobindo, a level of consciousness which enables a seeker to attain the integral knowledge of the Reality in all its aspects — transcendent, cosmic, individual, static, dynamic, impersonal, personal, spirit, soul, mind, life, matter.

The integral yoga has a twofold aim. First, to attain knowledge edge of the Reality in one or other of its aspects by the spiritualized mental consciousness. Secondly, to lift the consciousness in the seeker already in direct touch with the spiritual Reality to the supramental spiritual consciousness. For the supermind which is Truth-Conscious is in possession of the integral knowledge of the Divine. The supermind is God’s self-knowledge and world-knowledge. It is also simultaneously the Divine Will which is God’s Force of self-manifestation as the world in his own being. The world is to all intents and purposes an organization of three principles, viz. mind, life and matter. These are truly speaking levels and formations of Consciousness in which God is hidden and involved. The purpose of the integral yoga is to manifest the hidden divine supramental Knowledge-Will in them and to transform them by its power. Their transformation will turn mind, life and matter into the transparent means of revealing the hidden Divine in them. This radical change of mental, vital, and material Nature of several yogis will be the basis of the formation of a community of supermen. Their collective life will be directed by Knowledge unmixed with Ignorance, empowered by spontaneously effective Will and an expression of unitive Love. Their life will be the Life Divine.

Nolini Kanta is a name to reckon with in the history of man’s spiritual evolution. In spite of being an amazingly versatile talent bordering on genius, he was first and foremost a seeker of the spiritual life. Under the luminous and effective guidance of Sri Aurobindo and the Mother he blossomed into a yogi of high stature and all-round spiritual growth. A long time ago he made a clear choice. Not for him were the lures of the world, there was one thing to seek — the Mother of all creatures and existences. The poet in him gave expression to his preference thus:

Turn my gaze away from thousand nothingnesses —

One thing for me is enough and more

О Queen of hearts!

What avails the senses each to pursue its luring fire

That leads but to a dismal engulfing bog,

To nothingness or worse?

The Sense of the senses dwells at home

And through its moon-lit grace distills

Peace and ease and rapture exquisite!

The essence of delights, the secret sap of blooms,

The winkless Light beyond all flickerings,

The one treasure intimate — it is Thou!

My all has melted away and vanished

Into the single orb of thy compassion,

О my One and All!((( Nolini Kanta Gupta, Towards the Heights, The Culture Publishers, Calcutta, 1944, p. 36.)))

The note of rejection of transitory values is clear and loud. Not only that, the poet-seeker’s attraction for the Divine is beyond doubt. Nevertheless at times he feels

In Thee I am a perfect slave,

Sovereignly free and happy!

Without Thee I become the master

Bound head to foot, a figure of misery!

*

Thus he enjoins himself and others to

Aspire wholly,

Ask for the fullness of Grace —

But weigh not the measure of Response,

Nor repine if seems doled out scantily, niggardly,((( Ibid., p. 49.)))

Give yourself wholly and ever more and more,

It is your unreserved giving that will create the spaciousness

to hold safely the gift from the Divine.((( Op. cit., p. 49.)))

Acceptance of the Grace, however, in whatever measure it comes is an important step in the sadhana. For

The high wisdom knows and gives just what is needed —

Could we only rest contented and move in its rhythm and not transgress its will,

Serene would be the path and perfect and even prompt the achievement.((( Op. cit.)))

Nolini Kanta’s aspiration soars higher and he prays to the Lord that the voice of his silence may enter him rousing every atom of his being, till it vibrates to his Truth and is a harp of its utterance and its visible embodiment. He prays for strength and power to withstand the tumultuous surges of the wide world that rush towards him assured of victory. He hopes and aspires that they may roll back in confusion and turn away upon themselves and leave him as a virgin rock tranquil and ever firm on its pristine foundations.

Lord, this is my prayer:

May the voice of thy silence enter me —

Rousing every atom of my being,

Till it vibrates to thy Truth,

And is the harp of its utterance

And is its visible embodiment.

All the tumultuous, surges of the wide world

Rush towards me assured of victory —

May they roll back in confusion and turn away upon themselves

And leave me as a virgin rock

Tranquil and ever firm on its pristine foundations.

May the universe dissolve, may it vanish

Even like a dream —

And thou alone appear, thou alone abide

One in thy multitudinous reality,

I shall find a new world in Thee, a world made of Thee,

Therein each limb of mine shall realise its fullness of union with Thee

And shall taste utter felicity.((( Op. cit., p. 18.)))

The seeker has gained insight into the nature of Reality which reveals itself to him as Pure Consciousness and also as unconscious Matter. He sees clearly that

Spirit is Matter sublimated, Matter is Spirit crystallised

Soul is Body introvert, Body is Soul extravert.((( Op. cit., p. 11.)))

He has gained a new vision as is evident from his own description of it in the following lines:

My eyes have followed the lines of thy beauty,

The winging curves of grace that embody thee —

In a delight that was gathered to its core of utmost intensity,

To its height of supreme exquisiteness…

A light bathed them, a glory suffused them slowly —

A clear and vast vision entered,

stood face to face with Truth —

And the scales of Ignorance fell away!((( Op. cit., p. 26)))

He has developed subtle hearing and subtle touch. His “ears have drunk God’s voice — its ringing sweetness filtered through the depths of my being and it awakens crystal listenings that mirror and capture the Mother-harmony of immemorial spheres and God’s rhythm divine that graces and moulds his life”.((( Op. cit., p 26.))) And so his hands

… have touched the roses of thy feet —

The very soul of fragrance has passed into the substance

Of my transmuted earth….

This body has grown sheer into thee as if it were thy own limb!((( Op. cit., p. 27.)))

Nolini Kanta feels that there is a deluding midworld that with its lurid shadow divides heaven and earth. But he also feels confident that

… one day they shall come close

And the lightning fire leap out

To consume the shadow track

And turn it into the gleaming path

For Heaven to descend upon earth.((( Op. cit., p. 41)))

His ego has melted away. He breathes and moves and acts not for himself but for the beloved Lord of his life. He is a slave of His Will and a plaything in His sweet hands. His seeming ‘I’ is an empty thing that bubbles up with God’s breath as He chooses and utters and enshrines His iridescent Delight and sinks back again and melts into His tranced silence.((( Op. cit., p. 33.)))

All this effort at dissolving his ego and filling his being with the presence of the Lord and the might of the Mother gives him a new confidence. And he sings:

Thou hast proved, О mighty one,

that the meanest of things here below is rounded

with a divine ending,

and man is not all too human:

there is a prophecy in mortal creatures that only bides its time,

nothing is impossible even in this sorry world

For, behold, I am no longer what I was.((( Op. cit., pp. 31-32.)))

The newborn confidence is the armour in his assault on the higher levels of consciousness. Knowledge of the Self and union with the Divine equipped Nolini Kanta with the capacity to ascend to the spiritual mind of which there are many levels. At the end of his long life Nolini Kanta succeeded in elevating his consciousness to the Overmind plane. Along with this ascent his nature was also changing and evolving. Consequently he achieved a versatility of capacities which enabled him to engage quietly but successfully in various kinds of activities. Through this development of nature he was preparing to meet and unite with God in many aspects and along different lines. It can even be said that he had a foretaste of the culmination of the integral yoga,

I have heard His call and He has embraced me intimately from afar,

Lo, I am grown into the translucency of His divine serenity,

the earth-made cells of flesh are now spirit-stars

that bear the undecaying lustres of immortality.((( Op. cit., p. 34.)))