. . . a strange fear gripped me: how could I live a cloistered life in Pondicherry where there was no music or laughter? The strange thing was, perhaps, this curious fact that though I sang and laughed and delighted people I myself derived no pleasure from their society! I told none about my inner conflicts: how my aspiration to take to yoga was opposed tooth and nail by my intense reluctance and this nameless fear. How could I possibly renounce my freedom of movement and enter a monastery, a thousand miles away from Bengal? I neither knew anyone there nor had any idea of the technique of Sir Aurobindo’s “Supramental Yoga,” as many a devotee called it . . . and so my tussle with my crestfallen self went on interminably.

It was in this forlorn mood that I went to Lucknow where I met Krishnaprem’s dear friend Joygopal. He told me all about Krishnaprem though there was not much he could tell because in those days Krishnaprem never wrote to anybody about his yoga. So I gathered from Joygopal only tidbits of information about him, all of which conspired to deepen my gloom. What horrified me most was that Krishnaprem was actually begging alms in the streets and sleeping on a bare blanket on the cold heights of the Himalayas, 7,500 feet above sea level. My heart sank every time Joygopal put me abreast of his feats of courage and endurance, and I asked myself again and again, in trepidation, whether all these heroic austerities were incumbent on one who yearned desperately to be havened at his guru’s feet. But I found no answer, and so had to live in a void, since I had no taste left for the fleshpots of the world, and even music, my grande passion, had, alas, begun to pall.

So, one night, I confided to my friend my deep misgivings and told him that although I felt miserable I could not help but vacillate because I just dreaded cloistered monasticism. But that was not the whole story, as he divined quickly. So, astutely hitting the nail on the head and giving me a quizzical smile, Joygopal hazarded bluntly: “Don’t hedge, Dilip. I propose buying a ticket for you the first thing tomorrow morning. You just make straight for your guru’s yogashram at Pondicherry, where you belong. Surrender all you have and are to him.”

“It’s all very well to prescribe remedies,” I demurred ruefully. “But are you sure of the diagnosis?”

A medical man, my friend and host smiled appreciatively and prodded: “What is the nub of the trouble?”

“I wish I knew,” I answered bitterly. “I only know that I am groping in a maze. You see, it’s like this. My guru, unlike Krishnaprem’s, has not given me anything tangible yet. Surely, you don’t expect me to give up everything for nothing?”

His noble brow clouded.

“Well, Dilip,” he sighed. “You have let me down! I cherished you as I have because I thought you were a born yogi, like Krishnaprem. I see now that I was mistaken. For what you say amounts to this: that you can’t bring yourself to accept a guru unless he signs a contract with you and gives you in advance some delightful experiences — something like what they call in law a ‘consideration,’ a quid pro quo stipulation! Well, if this be your approach — that is, if you start by bargaining with the Lord — then you shall never arrive.”

The shaft went home. The whole night I could not sleep. I was bargaining with the Lord, whereas Krishnaprem had taken the plunge, staking everything with just one throw of the dice. . . . Oh, how dare I claim him as my friend after this? . . . A medley of self-pity and vacillation, aspiration and fear, longing and diffidence, drained me of all my strength till I started praying in tears — when the incredible miracle happened.

It is God’s truth that I got up and in twenty minutes took the next available train to Bombay, en route for Pondicherry. Just before leaving, I dispatched the following telegram to Sri Aurobindo: “I surrender unconditionally to you all I have and am. You must accept me. Wire yes to my friend Justice К. C. Sen, Bombay.”

What followed was an unforgettable experience: the whole landscape seemed to have changed in the twinkling of an eye! Once in London I had marveled at two scenes on the stage. In the first there were only thirsty sand dunes without a trace of vegetation. Suddenly the light went out, then click, the stage revolved and I saw in thrilled wonder a beautiful garden house with roses, palms and a fountain. My experience in 1928 was, indeed, far more apocalyptic: directly after my anguished conflicts and dark doubts there flashed a delectable certitude of security, an unutterable euphoria and, above all, a sense of belonging. I had no idea whither I was bound nor how long I would have to trudge on toward a far-off goal, against what odds. I only knew that all my misgivings had been dissolved, my doubts liquidated, my questionings stilled. Yet, outwardly, nothing had changed! The irksome railway journey, the babel of a jostling crowd, the harsh whistles, the railway porters to be dealt with — all this tedium of prose was transformed in a moment into a rhapsody, answering His Flute Call! How can I say after this that the age of miracles has passed? And the most baffling miracle was that my human destiny was decided once and for all, and in just twenty minutes, by a power beyond my ken. I had a rapturous glimpse of myself being carried along on the wave-crest of a light, which though unseen by the eye enthralled my soul.

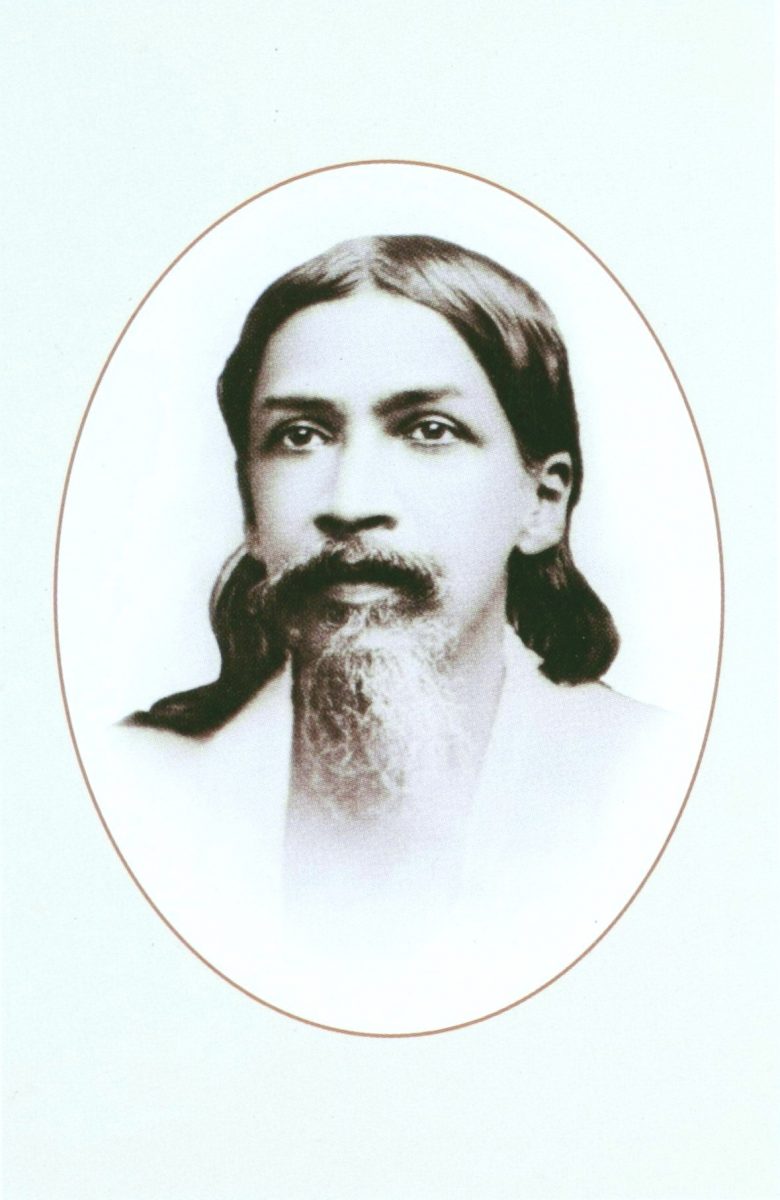

All this is not an overstatement of what uprooted me from my native soil of art and social intercourse to be transplanted into an alien garden at the feet of my radiant Guru of Grace, the deputy of my Dream-Lord Krishna. I received in Bombay, at the house of my friend Justice К. C. Sen, Sri Aurobindo’s telegram from Pondicherry. Thereafter, on November 22, 1928, I submitted to him myself, in an eager and joyous homecoming like a way-lost bird which had suddenly found its nest in the sky of sweet repose, bliss and security.

(the above is excerpt from the book by D. K Roy “Pilgrims of the Stars”)

About Savitri | B1C3-10 The New Sense (pp.29-31)