“… The force of a great stream of aspiration must be poured over the country, which will sweep away as in a flood the hesitations, the selfishnesses, the fears, the self-distrust, the want of fervour and the want of faith which stand in the way of the spread of the great national awakening of 1905. A mighty fountain of the spirit must be prepared from which this stream of aspiration can be poured to fertilise the heart of the nation. When this is done, the aspiration towards liberty will become universal and India be ready for the great effort.”

The Need of the Moment

— Bande Mataram, March 22, 1908

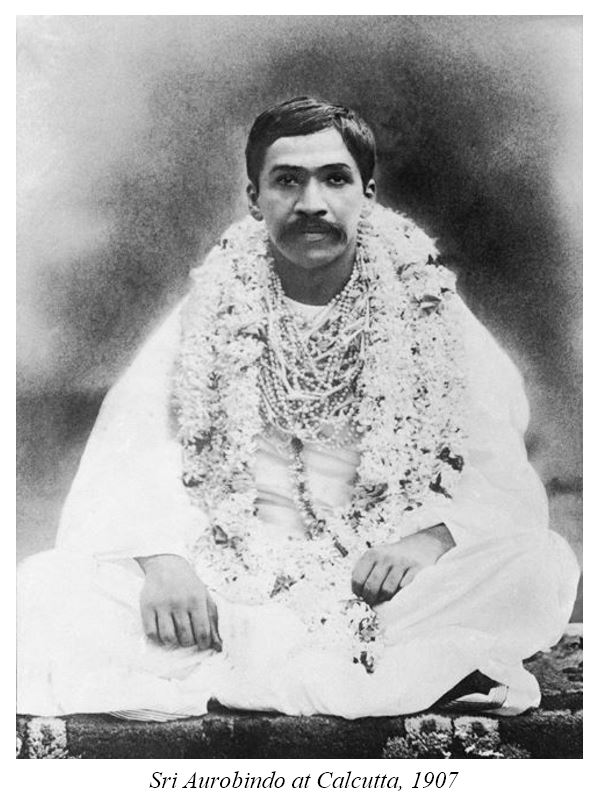

On June 2, 1907, the weekly edition of the Bande Mataram was started. In its second issue, dated 9th June, Sri Aurobindo’s patriotic poem, Vidula, began to be published in a serial form. We shall deal with this poem when, in due course, we take up the study of Sri Aurobindo’s poetry. Here we quote only a few lines from the introductory paragraph. Both the poem and its introduction breathe the patriotic fervour, spirit of freedom and impatience of servitude, which were inspiring Sri Aurobindo’s thoughts, writings and activities in Bengal at that time.

“There are few more interesting passages in the Mahabharata than the conversation of Vidula with her son. It comes into the main poem as an exhortation from Kunti to Yudhisthir to give up the weak spirit of submission, moderation, prudence, and fight like a true warrior and Kshatriya for right and justice and his own. But the poem bears internal evidence of having been written by a patriotic poet to stir his countrymen to revolt against the yoke of the foreigner…. The poet seeks to fire the spirit of the conquered and subject people and impel them to throw off the hated subjection. He personifies in Vidula the spirit of the motherland speaking to her degenerate son and striving to wake in him the inherited Aryan manhood and the Kshatriya’s preference of death to servitude.”

We may note here that in the 30th June issue of the weekly Bande Mataram appeared the first instalment of Sri Aurobindo’s drama, Perseus the Deliverer. In it, not the spirit of patriotism and revolt against political subjection and slavery, but the gigantic clash between the forces of Light and the forces of darkness, is portrayed in the guise of a romantic Greek myth. We shall study it also in our section on Sri Aurobindo’s poetry.

Both the popular papers, Yugantar and Bande Mataram were gall and wormwood to the British bureaucracy, which were watching for an opportunity to swoop down upon them and smother them to death. And an opportunity always comes handy to an autocrat. On the 7th June, 1907, the Bengal Government issued a warning to the Yugantar that police action would be taken against it if it persisted in publishing inflammatory, seditious articles. On the 8th June, 1907, a similar warning was given to the Bande Mataram. On the 3rd July, Yugantar office was searched. Bhupendra Nath Datta, youngest brother of Swami Vivekananda, declared that he was the editor of the paper and courted arrest.[1] He was sentenced to one year’s rigorous imprisonment, as we have already stated. His statement to the Court was a model of fearless defiance of the British Law and stark refusal to defend his case. On the 30th July, 1907, the Bande Mataram office was searched. On the 16th August a warrant was issued against Sri Aurobindo, who was charged with sedition for having published in the Bande Mataram, of which he was alleged to be the editor, English translations of some articles originally published in the Yugantar. On receiving the warrant, Sri Aurobindo went to the police court and offered himself for arrest. But, as there was no proof available of his being the editor of the Bande Mataram, he was soon acquitted. Bepin Chandra Pal, who was called as a witness, refused point-blank to give evidence or take any part in the prosecution, and was sentenced to six months’ simple imprisonment on a charge of contempt of court. Brahmabandhab Upadhyaya, editor of the Sandhya, was arrested on the 31st August, but, as he had predicted, he escaped the penalty of the British Law by departing from this life after a short illness. Thus the British Government strove to gag all public expression of nationalist feeling and yearning for freedom. But the suppression of the human spirit is a vain endeavour — it serves only to feed the spirit’s flame and stimulate its will to achieve its end. It was during Sri Aurobindo’s arrest that Rabindranath composed his famous poem as his tribute to Sri Aurobindo’s greatness. Later, he saw Sri Aurobindo at 12, Wellington Street and congratulated him on his acquittal.

But the suppression of the human spirit is a vain endeavour — it serves only to feed the spirit’s flame and stimulate its will to achieve its end. It was during Sri Aurobindo’s arrest that Rabindranath composed his famous poem as his tribute to Sri Aurobindo’s greatness. Later, he saw Sri Aurobindo at 12, Wellington Street and congratulated him on his acquittal.

The Bande Mataram case brought Sri Aurobindo at once into the full blaze of publicity, which he had studiously avoided so long. He became overnight, not only the undisputed leader of the Nationalist Party in Bengal, but one of the foremost leaders of the Nationalists in India. Writing on this subject, he says: “Sri Aurobindo had confined himself to writing and leadership behind the scenes, not caring to advertise himself or put forward his personality, but the imprisonment and exile of other leaders and the publicity given to his name by the case compelled him to come forward and take the lead on the public platform.”[2]

On the 2nd August, 1907, Sri Aurobindo resigned his post at the National College. About his resignation he writes: “At an early period he left the organisation of the College to the educationist Satish Mukherjee and plunged fully into politics. When the Bande Mataram case was brought against him he resigned his post in order not to embarrass the College authorities but resumed it again on his acquittal. During the Alipore case he resigned finally at the request of the College authorities.”[3] On the 22nd August Sri Aurobindo spoke to the students of the National College who had called a meeting to express their profound regret at his resignation of the post of the principalship of the College. We quote below only a few sentences from that speech:

“In the meeting you held yesterday I see that you expressed sympathy with me in what you call my present troubles. I don’t know whether I should call them troubles at all, for the experience that I am going to undergo was long foreseen as inevitable in the discharge of the mission that I have taken up from my childhood,[4] and I am approaching it without regret. What I want to be assured of is not so much that you feel sympathy for me in my troubles but that you have sympathy for the cause, in serving which I have to undergo what you call my troubles. If I know that the rising generation has taken up this cause, that wherever I go, I go leaving behind others to carry on my work, I shall go without the least regret. I take it that whatever respect you have shown to me today was shown not to me, not merely even to the Principal, but to the country, to the Mother in me,[5] because what little I have done has been done for her, and the slight suffering that I am going to endure will be endured for her sake…. When we established this college and left other occupations, other chances of life, to devote our lives to this institution, we did so because we hoped to see in it the foundation, the nucleus of a nation, of the new India which is to begin its career after this night of sorrow and trouble, on that day of glory and greatness when India will work for the world. What we want here is not merely to give you a little information, not merely to open to you careers for earning a livelihood, but to build up sons for the Motherland to work and to suffer for her…. There are times in a nation’s history when Providence places before it one work, one aim, to which everything else, however high and noble in itself, has to be sacrificed. Such a time has now arrived for our Motherland when nothing is dearer than her service, when everything else has to be directed to that end. If you will study, study for her sake; train yourselves body and mind and soul for her service. You will earn your living that you may live for her sake. You will go abroad to foreign lands that you may bring back knowledge with which you may do service to her. Work that she may prosper. Suffer that she may rejoice…”[6]

This lofty, ardent, inspiring tone characterised all that Sri Aurobindo spoke and wrote in his political days in Bengal. But there are three things in the above extract which attract our special attention: First, “the experience that I am going to undergo was long foreseen as inevitable in the discharge of the mission that I have taken up from my childhood…” Second, “whatever respect you have shown to me today was shown not to me, not merely even to the Principal, but to your country, to the Mother in me…” Third, “that day of glory and greatness when India will work for the world.”

The first point brings home to us again the fact that Sri Aurobindo had a more or less definite conception — it was, indeed, a foreknowledge[7] — even in his childhood, of the mission of his life. This foreknowledge is not something very rare; it has been a usual, if rather extraordinary, phenomenon in the lives of the supreme prophets, poets and pioneers. Goethe had it, Sri Ramakrishna and Swami Vivekananda had it. The second point indicates his Yogic identification with Mother India in whom he had realised the Divine Mother. He was well advanced in Yoga at the time when he spoke these words, as his letters to his wife attest. No other leader, even in his most inspired flights, would have presumed to speak of “the Mother in me”! The utter effacement of his personal self in the Divine Mother had resulted in this identification. The third point is a reiteration of what he always knew and preached, whenever he spoke of the future greatness of India, that “India will work for the world.” His nationalism, as we have already said before, was supernational, it was universal. India is rising, not for herself, but for the world, for all humanity.

The Midnapore Provincial Conference took place from 7th to 9th November, 1907. Dr. R.C. Majumdar says in his monumental (three-volume) History of the Freedom Movement in India that it was as the leader of the Nationalists that Sri Aurobindo took part in this Conference, “a conference made memorable by the first open rupture between the Moderates and the Extremists of our province.” About the same conference Sri Aurobindo writes: “He (Sri Aurobindo) led the party at the session of the Bengal Provincial Conference at Midnapore where there was a vehement clash between the two parties (the Nationalists or Extremists and the Moderates). He now for the first time became a speaker on the public platform…”[8] Surendra Nath Banerjee, Shyam Sundar Chakravarty and many other leaders of both the parties had gone to Midnapore. The Moderates were led by Surendra Nath and the President-elect was K.B. Datta. But after the rift, the Nationalists held a separate Conference under the leadership of Sri Aurobindo, and also elected him their President. The Midnapore clash and rupture were only a prelude to what was going to take place at the Surat Congress.

Writing on the Midnapore Conference, Dr. R.C. Majumdar says: “…Towards the end of the year (1907), the same fear (that the Moderates would make an attempt to omit the resolutions already passed on Self-government, Swadeshi, Boycott, and National Education at the Calcutta session of the Congress in 1906) was further enhanced by the incidents at the District Congress Conference, held at Midnapore (Bengal). Surendra Nath tried his best to convince Aravinda that the Moderate policy would not only bring about the re-union of Bengal but even a great measure of self-government within a short period. Aravinda, however, did not yield. Rowdyism broke out on account of differences between the two parties, particularly on the refusal of the Chairman to discuss Swaraj, and the police had to be called in to restore order.”[9]

The twenty-third Indian National Congress commenced its proceedings at Surat on 26th December, 1907. We have from Sri Aurobindo himself a pretty long description of what happened at this Congress: “…The session of the Congress had first been arranged at Nagpur, but Nagpur was a predominantly Mahratta city and violently extremist. Gujerat was at that time predominantly Moderate, there were very few Nationalists and Surat was a stronghold of Moderatism though afterwards Gujerat became, especially after Gandhi took the lead, one of the most revolutionary of the provinces. So the Moderate leaders decided to hold the Congress at Surat. The Nationalists however came there in strength from all parts, they held public conference with Sri Aurobindo as President and for some time it was doubtful which side would have the majority…. It was known that the Moderate leaders had prepared a new constitution for the Congress which would make it practically impossible for the extreme party to command a majority at any annual session for many years to come. The younger Nationalists, especially those from Maharashtra, were determined to prevent this by any means and it was decided by them to break the Congress if they could not swamp it; this decision was unknown to Tilak and the older leaders. But it was known to Sri Aurobindo.[10] At the session Tilak went on to the platform to propose a resolution regarding the presidentship of the Congress; the President appointed by the Moderates refused to him the permission to speak, but Tilak insisted on his right and began to read his resolution and speak. There was a tremendous uproar, the young Gujerati volunteers lifted up chairs over the head of Tilak to beat him. At that the Mahrattas became furious, a Mahratta shoe came hurtling across the pavilion aimed at the President, Dr. Rash Behari Ghose, and hit Surendra Nath Banerjee on the shoulder. The young Mahrattas in a body charged up to the platform, the Moderate leaders fled; after a short fight on the platform with chairs, the session broke up not to be resumed.”[11]

Nevinson in his book, The New Spirit in India, has given a graphic description of this tumult and uproar at the Surat Congress where he was present. K.M. Munshi, an ex-Governor of the U.P. has also given a detailed description of the same fray in the Bhavan’s Journal of November 27, 1960.

[1] He refused to defend himself under Sri Aurobindo’s instructions, “…the Yugantar under Sri Aurobindo’s orders adopted the policy of refusing to defend itself in a British Court…” — Sri Aurobindo on Himself and on The Mother

[2] Sri Aurobindo on Himself and on The Mother.

[3] Sri Aurobindo on Himself and on The Mother.

[4] Italics are ours.

[5] Italics are ours.

[6] Speeches of Sri Aurobindo.

[7] He uses the word “foreseen”.

[8] Sri Aurobindo on Himself and on The Mother.

[9] History of the Freedom Movement in India, Vol. II.

[10] “Very few people knew that it was I (without consulting Tilak) who gave the order that led to the breaking of the Congress and was responsible for the refusal to join the new-fangled Moderate Convention…” Sri Aurobindo on Himself and on The Mother.

[11] Sri Aurobindo on Himself and on The Mother.

About Savitri | B1C3-10 The New Sense (pp.29-31)