The year 2020 is clearly one that cannot be easily forgotten. The most significant even has of course been the pandemic and the fever of fear that has gripped mankind right at its very throat. It is as if stifling man, pushing him towards a narrow gorge where he has either to face the challenge of death or let himself be born to a new life. It is also a year of massive geo-political shifts leading to new alignments among nations and within groups of humanity. The year is also witnessing another shift that is subtle and yet not to subtle in the human thinking and its way of life. It is as if a mighty Force is working upon earth and mankind that is churning the human consciousness swiftly in unprecedented ways like the great sea-churning of old. This ancient tale of the churning of the ocean is therefore not just an ancient myth and fable but a deeply symbolic story that is at once contemporary and relevant to what we are going through at this point of time. Many gifts emerge out of this great churning which go to different participants but all eyes are set on the nectar of immortality. As the event is approaching its close there emerges out of the ocean deeps the dark and dangerous fumes whose poison threatens the whole world. Shiva, the Lord of tapasya consumes it and frees the world for the emergence of the nectar. But now it is the turn for Vishnu, the great preserver of dharma who sustains the balance of the worlds to intervene and see to it that the nectar reaches the right recipients, the adhikari who want it not for any personal egoistic enjoyment or furtherance of their personal garden of pleasure but only as a means to enhance the forces of Light and Truth and Beauty and Love and Harmony upon earth. Today also we are each individually and collectively facing a choice whether we want the future only for the expansion of our ego’s empire driven the ambitious Rakshasa and Asura within us or use the strength and energies given to us to establish a new world-order based on dharma and truth, a world where unity and freedom and fraternity reigns, a world which is freed of the menace of the Asura, a world where the animal in man is placed at the service of his higher illumined intellect and not a force that restlessly goes about its own petty round of desires and satisfactions of the body and the vital. Depending upon the choices we make today the doors of future shall open for us. After all it is the centenary year of the permanent return of the Divine Mother, the Avatara of the supreme Shakti, to India, the land She chose for Her mighty Work along with Her divine and eternal companion, the Lord of Yoga Sri Aurobindo who along with Her have opened the doors of a New Age of mankind. All that witnessing today and all that we yet shall witness in years to come will be a means to prepare us for Her coming. The difference however will be that this time She is not returning only to a material space, Her karmabhoomi, Pondicherry but to the whole earth and most importantly She is coming to open and build a temple of Her and the Lord in the heart of man. It is clearly a period of great transition whose impact will remain imprinted upon us for a long time to come.

The Indian mind, sensitive always to such events that have turned the tides of time and reshaped the history of earth has captured them in myths and legends and stories that have openly or subtly governed the thought and mind of the race, inspired its heart and awakened its soul to these deeper truths that are often forgotten in the blind race of life driven by our usual desires and ambitions. The two great epics that have governed the psyche of the ancient Indian people and whose charm and appeal are perennial and continues in our modern times are the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. Both are stories woven around a great war that changed the course of history. Both have at their centre the Avatara, the conscious descent of the Divine in animal and human forms for the redemption of earth and humanity. Though the essential significance of both epics is same, their scopes are very different. The Ramayana belongs to an earlier stage of evolution when the animal, rakshasic and asuric humanity is struggling evolve into a more humanised type. Given the nature of humanity that one is dealing with here the epic also stays faithful to its style. We find here the simple animal-humanity still one with nature, raw in its dealings with life yet undefiled by all the complexities brought in by the human mind and its excessive development. In the Mahabharata the evolutionary crisis is no more between the Asura and man with the animal type called upon to make its choices. Here the struggle and conflict is between two types of humanity. One that belongs to the old consciousness that has albeit lost its way, dharmasya glanir, and struggles to find its way towards the future. The other belongs to the new type of humanity that comes as instruments of the Divine to uphold the dharma and lead man through the conflict towards a new way of being. The characters are heroic human beings but also experts in both astras (weapons) and shastras (scriptural knowledge). They are complex and being largely mentalised we can identify in them quite a few archetypes of our own times. It is for this reason that the Mahabharata often appeals more to the modern mind than the Ramayana. However, the Ramayana contains something precious, even indispensable for human progress and it is the deeper heart, the emotional being that can open rather easily to soul-influence. That is why Ramayana appeals much more to the heart and soul whereas the Mahabharata to the mind and the moral/ ethical dilemmas we face. Perhaps realising this deficit of the heart which makes an epic rich and beautiful we find, in the Mahabharata, interspersed as it were the exploits of Sri Krishna, the Avatara of Dwapara. The images of Sri Krishna lila drawn from the Mahabharata as well as the Bhagawat Purana have governed the Indian psyche for long and inspired the heart towards bhakti and that complete love and surrender to God. It is not just a clash of civilisations and ideologies that we find as the central theme but a clash of two types of humanity, two lines of evolutionary development through which humanity passes from time to time in its long and complex winding road towards some high and far off destiny.

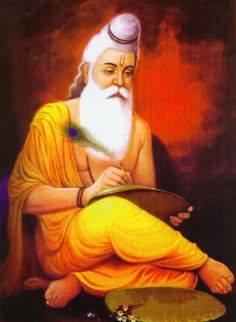

The epics reveal to us the road that man must take in his evolutionary journey. It is conjured in that one word, dharma which has fascinated the Indian mind since the Aryan forefathers moved through the mountains and plains and rivers flowing through the subcontinent we know today as India. The stamp of the Ramayana and the Mahabharata can be found everywhere here. We find the mention of its mountains and rivers, its sacred places, the kingdoms and cities and hermitages of Rishis along river banks and forests. It is amazing how the great epics have been carried through the generations; their inspiring influence sown as a seed in the early stages of development of a nation is a unique example of creating a nation from within outwards. Unlike most modern nations India has a very long history of development. At first is sown a seed in the form of high spiritual aspiration and an account of the realisations of the Rishis who forged the soul of this land and its people. Once the soul was awakened and the body generally defined surrounded by the mountain and the seas, then the Rishis started shaping its mind and inner being through the great philosophies and epics. The epics were particularly helpful in shaping our ethical mind, refining the vital energies, purifying the emotional being, teaching and training the twin great powers of sacrifice and renunciation through which we arrive at a greater perfection intended for man. But since even the highest and noblest of aspirations need an outer body and flesh here upon earth there developed around these central truths keeping them as a base, certain ways of life and customs even celebrations to imprint the soul-memories of India’s glorious past to help the generations to come so that invigorated and enlightened by these soul-imprints we may move towards a yet greater future. But these great epics and books of Wisdom were never allowed to crystallise into fixed and dogmatic, rigid religious formulas. This did happen thought as a means of self defence when India was exposed to barbaric and alien cultures. It was the spirit of conservation, a matter of extreme necessity and not its original way of life which was always built on a harmonious ground where law and liberty worked together. The name given to this harmonious synthesis of law and liberty is what is called as Dharma.

The epics reveal to us the road that man must take in his evolutionary journey. It is conjured in that one word, dharma which has fascinated the Indian mind since the Aryan forefathers moved through the mountains and plains and rivers flowing through the subcontinent we know today as India. The stamp of the Ramayana and the Mahabharata can be found everywhere here. We find the mention of its mountains and rivers, its sacred places, the kingdoms and cities and hermitages of Rishis along river banks and forests. It is amazing how the great epics have been carried through the generations; their inspiring influence sown as a seed in the early stages of development of a nation is a unique example of creating a nation from within outwards. Unlike most modern nations India has a very long history of development. At first is sown a seed in the form of high spiritual aspiration and an account of the realisations of the Rishis who forged the soul of this land and its people. Once the soul was awakened and the body generally defined surrounded by the mountain and the seas, then the Rishis started shaping its mind and inner being through the great philosophies and epics. The epics were particularly helpful in shaping our ethical mind, refining the vital energies, purifying the emotional being, teaching and training the twin great powers of sacrifice and renunciation through which we arrive at a greater perfection intended for man. But since even the highest and noblest of aspirations need an outer body and flesh here upon earth there developed around these central truths keeping them as a base, certain ways of life and customs even celebrations to imprint the soul-memories of India’s glorious past to help the generations to come so that invigorated and enlightened by these soul-imprints we may move towards a yet greater future. But these great epics and books of Wisdom were never allowed to crystallise into fixed and dogmatic, rigid religious formulas. This did happen thought as a means of self defence when India was exposed to barbaric and alien cultures. It was the spirit of conservation, a matter of extreme necessity and not its original way of life which was always built on a harmonious ground where law and liberty worked together. The name given to this harmonious synthesis of law and liberty is what is called as Dharma.

Sri Aurobindo reveals the truth of Avatarahood and Dharma in Essays on the Gita:

It is, we might say, to exemplify the possibility of the Divine manifest in the human being, so that man may see what that is and take courage to grow into it. It is also to leave the influence of that manifestation vibrating in the earth-nature and the soul of that manifestation presiding over its upward endeavour. It is to give a spiritual mould of divine manhood into which the seeking soul of the human being can cast itself. It is to give a dharma, a religion, — not a mere creed, but a method of inner and outer living, — a way, a rule and law of self-moulding by which he can grow towards divinity. It is too, since this growth, this ascent is no mere isolated and individual phenomenon, but like all in the divine world-activities a collective business, a work and the work for the race, to assist the human march, to hold it together in its great crises, to break the forces of the downward gravitation when they grow too insistent, to uphold or restore the great dharma of the Godward law in man’s nature, to prepare even, however far off, the kingdom of God, the victory of the seekers of light and perfection, sādhūnām, and the overthrow of those who fight for the continuance of the evil and the darkness. All these are recognised objects of the descent of the Avatar, and it is usually by his work that the mass of men seek to distinguish him and for that that they are ready to worship him. It is only the spiritual who see that this external Avatarhood is a sign, in the symbol of a human life, of the eternal inner Godhead making himself manifest in the field of their own human mentality and corporeality so that they can grow into unity with that and be possessed by it. The divine manifestation of a Christ, Krishna, Buddha in external humanity has for its inner truth the same manifestation of the eternal Avatar within in our own inner humanity. That which has been done in the outer human life of earth, may be repeated in the inner life of all human beings….

The outward action of the Avatar is described in the Gita as the restoration of the Dharma; when from age to age the Dharma fades, languishes, loses force and its opposite arises, strong and oppressive, then the Avatar comes and raises it again to power; and as these things in idea are always represented by things in action and by human beings who obey their impulsion, his mission is, in its most human and outward terms, to relieve the seekers of the Dharma who are oppressed by the reign of the reactionary darkness and to destroy the wrong-doers who seek to maintain the denial of the Dharma. But the language used can easily be given a poor and insufficient connotation which would deprive Avatarhood of all its spiritual depth of meaning. Dharma is a word which has an ethical and practical, a natural and philosophical and a religious and spiritual significance, and it may be used in any of these senses exclusive of the others, in a purely ethical, a purely philosophical or a purely religious sense. Ethically it means the law of righteousness, the moral rule of conduct, or in a still more outward and practical significance social and political justice, or even simply the observation of the social law. If used in this sense we shall have to understand that when unrighteousness, injustice and oppression prevail, the Avatar descends to deliver the good and destroy the wicked, to break down injustice and oppression and restore the ethical balance of mankind….

The Avatar may descend as a great spiritual teacher and saviour, the Christ, the Buddha, but always his work leads, after he has finished his earthly manifestation, to a profound and powerful change not only in the ethical, but in the social and outward life and ideals of the race. He may, on the other hand, descend as an incarnation of the divine life, the divine personality and power in its characteristic action, for a mission ostensibly social, ethical and political, as is represented in the story of Rama or Krishna; but always then this descent becomes in the soul of the race a permanent power for the inner living and the spiritual rebirth.

On the other hand the life of Rama and Krishna belongs to the prehistoric past which has come down only in poetry and legend and may even be regarded as myths; but it is quite immaterial whether we regard them as myths or historical facts, because their permanent truth and value lie in their persistence as a spiritual form, presence, influence in the inner consciousness of the race and the life of the human soul. Avatarhood is a fact of divine life and consciousness which may realise itself in an outward action, but must persist, when that action is over and has done its work, in a spiritual influence; or may realise itself in a spiritual influence and teaching, but must then have its permanent effect, even when the new religion or discipline is exhausted, in the thought, temperament and outward life of mankind.

We must then, in order to understand the Gita’s description of the work of the Avatar, take the idea of the Dharma in its fullest, deepest and largest conception, as the inner and the outer law by which the divine Will and Wisdom work out the spiritual evolution of mankind and its circumstances and results in the life of the race. Dharma in the Indian conception is not merely the good, the right, morality and justice, ethics; it is the whole government of all the relations of man with other beings, with Nature, with God, considered from the point of view of a divine principle working itself out in forms and laws of action, forms of the inner and the outer life, orderings of relations of every kind in the world. Dharma1 is both that which we hold to and that which holds together our inner and outer activities. In its primary sense it means a fundamental law of our nature which secretly conditions all our activities, and in this sense each being, type, species, individual, group has its own dharma. Secondly, there is the divine nature which has to develop and manifest in us, and in this sense dharma is the law of the inner workings by which that grows in our being. Thirdly, there is the law by which we govern our outgoing thought and action and our relations with each other so as to help best both our own growth and that of the human race towards the divine ideal.

Dharma is generally spoken of as something eternal and unchanging, and so it is in the fundamental principle, in the ideal, but in its forms it is continually changing and evolving, because man does not already possess the ideal or live in it, but aspires more or less perfectly towards it, is growing towards its knowledge and practice. And in this growth dharma is all that helps us to grow into the divine purity, largeness, light, freedom, power, strength, joy, love, good, unity, beauty, and against it stands its shadow and denial, all that resists its growth and has not undergone its law, all that has not yielded up and does not will to yield up its secret of divine values, but presents a front of perversion and contradiction, of impurity, narrowness, bondage, darkness, weakness, vileness, discord and suffering and division, and the hideous and the crude, all that man has to leave behind in his progress. This is the adharma, not-dharma, which strives with and seeks to overcome the dharma, to draw backward and downward, the reactionary force which makes for evil, ignorance and darkness. Between the two there is perpetual battle and struggle, oscillation of victory and defeat in which sometimes the upward and sometimes the downward forces prevail. This has been typified in the Vedic image of the struggle between the divine and the Titanic powers, the sons of the Light and the undivided Infinity and the children of the Darkness and Division, in Zoroastrianism by Ahuramazda and Ahriman, and in later religions in the contest between God and his angels and Satan or Iblis and his demons for the possession of human life and the human soul.

It is these things that condition and determine the work of the Avatar. In the Buddhistic formula the disciple takes refuge from all that opposes his liberation in three powers, the dharma, the saṅgha, the Buddha. So in Christianity we have the law of Christian living, the Church and the Christ. These three are always the necessary elements of the work of the Avatar. He gives a dharma, a law of self-discipline by which to grow out of the lower into the higher life and which necessarily includes a rule of action and of relations with our fellowmen and other beings, endeavour in the eightfold path or the law of faith, love and purity or any other such revelation of the nature of the divine in life. Then because every tendency in man has its collective as well as its individual aspect, because those who follow one way are naturally drawn together into spiritual companionship and unity, he establishes the saṅgha, the fellowship and union of those whom his personality and his teaching unite. In Vaishnavism there is the same trio, bhāgavata, bhakta, bhagavān, — the bhāgavata, which is the law of the Vaishnava dispensation of adoration and love, the bhakta representing the fellowship of those in whom that law is manifest, bhagavān, the divine Lover and Beloved in whose being and nature the divine law of love is founded and fulfils itself. The Avatar represents this third element, the divine personality, nature and being who is the soul of the dharma and the saṅgha, informs them with himself, keeps them living and draws men towards the felicity and the liberation.

In the teaching of the Gita, which is more catholic and complex than other specialised teachings and disciplines, these things assume a larger meaning. For the unity here is the all-embracing Vedantic unity by which the soul sees all in itself and itself in all and makes itself one with all beings. The dharma is therefore the taking up of all human relations into a higher divine meaning; starting from the established ethical, social and religious rule which binds together the whole community in which the God-seeker lives, it lifts it up by informing it with the Brahmic consciousness; the law it gives is the law of oneness, of equality, of liberated, desireless, God-governed action, of God-knowledge and self-knowledge enlightening and drawing to itself all the nature and all the action, drawing it towards divine being and divine consciousness, and of God-love as the supreme power and crown of the knowledge and the action. The idea of companionship and mutual aid in God-love and God-seeking which is at the basis of the idea of the saṅgha or divine fellowship, is brought in when the Gita speaks of the seeking of God through love and adoration, but the real saṅgha of this teaching is all humanity. The whole world is moving towards this dharma, each man according to his capacity, — “it is my path that men follow in every way,” — and the God-seeker, making himself one with all, making their joy and sorrow and all their life his own, the liberated made already one self with all beings, lives in the life of humanity, lives for the one Self in humanity, for God in all beings, acts for lokasaṅgraha, for the maintaining of all in their dharma and the Dharma, for the maintenance of their growth in all its stages and in all its paths towards the Divine. For the Avatar here, though he is manifest in the name and form of Krishna, lays no exclusive stress on this one form of his human birth, but on that which it represents, the Divine, the Purushottama, of whom all Avatars are the human births, of whom all forms and names of the Godhead worshipped by men are the figures. The way declared by Krishna here is indeed announced as the way by which man can reach the real knowledge and the real liberation, but it is one that is inclusive of all paths and not exclusive. For the Divine takes up into his universality all Avatars and all teachings and all dharmas.

The Gita lays stress upon the struggle of which the world is the theatre, in its two aspects, the inner struggle and the outer battle. In the inner struggle the enemies are within, in the individual, and the slaying of desire, ignorance, egoism is the victory. But there is an outer struggle between the powers of the Dharma and the Adharma in the human collectivity. The former is supported by the divine, the godlike nature in man, and by those who represent it or strive to realise it in human life, the latter by the Titanic or demoniac, the Asuric and Rakshasic nature whose head is a violent egoism, and by those who represent and strive to satisfy it. This is the war of the Gods and Titans, the symbol of which the old Indian literature is full, the struggle of the Mahabharata of which Krishna is the central figure being often represented in that image; the Pandavas who fight for the establishment of the kingdom of the Dharma, are the sons of the Gods, their powers in human form, their adversaries are incarnations of the Titanic powers, they are Asuras. This outer struggle too the Avatar comes to aid, directly or indirectly, to destroy the reign of the Asuras, the evil-doers, and in them depress the power they represent and to restore the oppressed ideals of the Dharma. He comes to bring nearer the kingdom of heaven on earth in the collectivity as well as to build the kingdom of heaven within in the individual human soul.

The inner fruit of the Avatar’s coming is gained by those who learn from it the true nature of the divine birth and the divine works and who, growing full of him in their consciousness and taking refuge in him with their whole being, manmayā mām upāśritāḥ, purified by the realising force of their knowledge and delivered from the lower nature, attain to the divine being and divine nature, madbhāvam. The Avatar comes to reveal the divine nature in man above this lower nature and to show what are the divine works, free, unegoistic, disinterested, impersonal, universal, full of the divine light, the divine power and the divine love. He comes as the divine personality which shall fill the consciousness of the human being and replace the limited egoistic personality, so that it shall be liberated out of ego into infinity and universality, out of birth into immortality. He comes as the divine power and love which calls men to itself, so that they may take refuge in that and no longer in the insufficiency of their human wills and the strife of their human fear, wrath and passion, and liberated from all this unquiet and suffering may live in the calm and bliss of the Divine.

[CWSA 19: 159-160, 169, 170, 170-176]