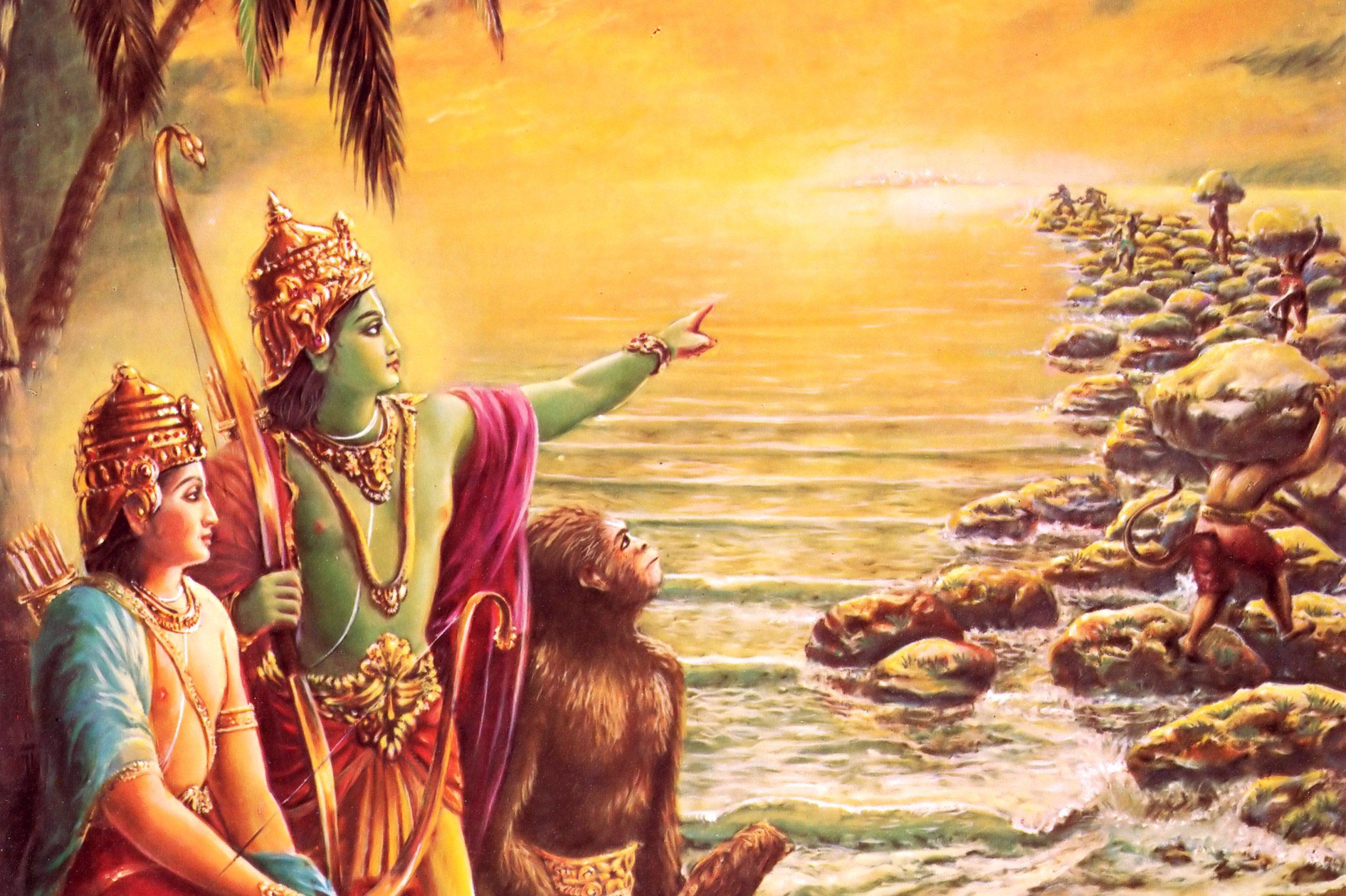

‘The Ramayana is a work of the same essential kind as the Mahabharata; it differs only by a greater simplicity of plan, a more delicate ideal temperament and a finer glow of poetic warmth and colour. The main bulk of the poem in spite of much accretion is evidently by a single hand and has a less complex and more obvious unity of structure. There is less of the philosophic, more of the purely poetic mind, more of the artist, less of the builder. The whole story is from beginning to end of one piece and there is no deviation from the stream of the narrative. At the same time there is a like vastness of vision, an even more wide-winged flight of epic sublimity in the conception and sustained richness of minute execution in the detail. The structural power, strong workmanship and method of disposition of the Mahabharata remind one of the art of the Indian builders, the grandeur and boldness of outline and wealth of colour and minute decorative execution of the Ramayana suggest rather a transcript into literature of the spirit and style of Indian painting. The epic poet has taken here also as his subject an Itihasa, an ancient tale or legend associated with an old Indian dynasty and filled it in with detail from myth and folklore, but has exalted all into a scale of grandiose epic figure that it may bear more worthily the high intention and significance. The subject is the same as in the Mahabharata, the strife of the divine with the titanic forces in the life of the earth, but in more purely ideal forms, in frankly supernatural dimensions and an imaginative heightening of both the good and the evil in human character. On one side is portrayed an ideal manhood, a divine beauty of virtue and ethical order, a civilization founded on the Dharma and realising an exaltation of the moral ideal which is presented with a singularly strong appeal of aesthetic grace and harmony and sweetness; on the other are wild and anarchic and almost amorphous forces of superhuman egoism and self-will and exultant violence, and the two ideas and powers of mental nature living and embodied are brought into conflict and led to a decisive issue of the victory of the divine man over the Rakshasa. All shade and complexity are omitted which would diminish the single purity of the idea, the representative force in the outline of the figures, the significance of the temperamental colour and only so much admitted as is sufficient to humanise the appeal and the significance. The poet makes us conscious of the immense forces that are behind our life and sets his action in a magnificent epic scenery, the great imperial city, the mountains and the ocean, the forest and wilderness, described with such a largeness as to make us feel as if the whole world were the scene of his poem and its subject the whole divine and titanic possibility of man imaged in a few great or monstrous figures. The ethical and the aesthetic mind of India have here fused themselves into a harmonious unity and reached an unexampled pure wideness and beauty of self-expression. The Ramayana embodied for the Indian imagination its highest and tenderest human ideals of character, made strength and courage and gentleness and purity and fidelity and self-sacrifice familiar to it in the suavest and most harmonious forms coloured so as to attract the emotion and the aesthetic sense, stripped morals of all repellent austerity on one side or on the other of mere commonness and lent a certain high divineness to the ordinary things of life, conjugal and filial and maternal and fraternal feeling, the duty of the prince and leader and the loyalty of follower and subject, the greatness of the great and the truth and worth of the simple, toning things ethical to the beauty of a more psychical meaning by the glow of its ideal hues. The work of Valmiki has been an agent of almost incalculable power in the moulding of the cultural mind of India: it has presented to it to be loved and imitated in figures like Rama and Sita, made so divinely and with such a revelation of reality as to become objects of enduring cult and worship, or like Hanuman, Lakshmana, Bharata the living human image of its ethical ideals; it has fashioned much of what is best and sweetest in the national character, and it has evoked and fixed in it those finer and exquisite yet firm soul tones and that more delicate humanity of temperament which are a more valuable thing than the formal outsides of virtue and conduct.’ Sri Aurobindo, The Renaissance in India1)

A temple for Rama is being built in his birthplace Ayodhya, the ancient city envied even by the gods. It is being built on the place where Rama was born in the Age of Silver known as the Treta Yuga in Indian history. Rama as we know was the finest flower of the lineage of Ikshavaku, also known as Suryavanshi kings of the Solar Dynasty tracing their origins to the legendary Manu who built the invincible city of Ayodhya on the banks of river Saryu. Sri Aurobindo translates a portion from Valmiki Ramayana, a sublime poetic creation that he ranked among the three greatest poetic genius of India, the other two being Vyasa and Kalidas. The portion translated by Sri Aurobindo gives a brief description of the city thus.

‘An Aryan City

Coshala named, a mighty country there was, swollen and glad; seated on the banks of the Sarayu it abounded in wealth & grain; and there was the city Ayodhya famed throughout the triple world, built by Manu himself, lord of men. Twelve leagues was the beautiful mighty city in its length, three in its breadth; large & clearcut were its streets, and a vast clearcut highroad adorned it that ever was sprinkled with water and strewn freely with flowers. Dasaratha increasing a mighty nation peopled that city, like a king of the gods in his heavens; a town of arched gateways he made it, and wide were the spaces between its shops; full was it of all machines and implements and inhabited by all kinds of craftsmen and frequented by herald and bard, a city beautiful of unsurpassed splendours; lofty were its bannered mansions, crowded was it with hundreds of hundred-slaying engines of war, and in all quarters of the city there were theatres for women and there were gardens and mango-groves and the ramparts formed a girdle round its spacious might; hard was it for the foe to enter, hard to assail, for difficult and deep was the city’s moat; filled it was of horses & elephants, cows and camels and asses, crowded with its tributary kings arrived for sacrifice to the gods, rich with merchants from many lands and glorious with palaces built of precious stone high-piled like hills & on the house-tops pleasure-rooms; like Indra’s Amarávati Ayodhya seemed.’ Sri Aurobindo, Translations from Ramayana ((([CWSA 5:23])))

The Ikshavaku dynasty was known for its nobility and might and above all for their truthfulness and included kings like Ikshavaku, Raghu, Harishchandra, Dilip, Sagar, Bhagirath, Shivi and many others who safeguarded Aryavart, the ancient name of India as described in Scriptures surrounded by the majestic Himalayas on the northern side and the sea on the three sides. Here again we see Sri Aurobindo translating a portion from Kalidasa describing the opening scene of his masterpiece Raghuvansham, the clan of Raghu about the lineage of Rama.

‘They who were perfect from their birth, whose effort ceased only with success, lords of earth to the ocean’s edge, whose chariots’ path aspired into the sky;

They of faultless sacrifices, they of the suppliants honoured to the limit of desire, punishing like the offence and to the moment vigilant.

Only to give they gathered wealth, only for truth they ruled their speech, only for glory they went forth to the fight, only for offspring they lit the household fire.

Embracers in childhood of knowledge, seekers in youth after joy, followers in old age of the anchoret’s path, they in death through God-union their bodies left.‘ Sri Aurobindo, translations from Kalidasa2)

Rama is also regarded as the seventh Avatar of God Vishnu, the preserver of Dharma.

Time and space does not permit us to take up all the beauty and charm of Ramayana. Yet it will do good to read something from Sri Aurobindo about the great epic and its impact upon the Indian Psyche and moulding its life and culture. Rama is like a bright lamp holding before mankind, yet largely driven by the animal and asuric nature, the way towards a high consummation of our manhood. If his nobility and idealism, strength and power, mildness of nature combined with strength of character, joining saumya (calm and gentle benevolence) with raudra (might, courage and fearlessness) are yet to be generalized in the human race, his virtue as a king are yet to be surpassed. For Rama, Rajdharma is important above all. He is ready and willing to sacrifice his personal happiness to set the highest standard of public probity for a Ruler. His democratic values will not crush down the freedom of a commoner to question the king and his conduct as we see in the tragic turn of events when he must abandon Sita for whose love he has taken on the challenge of the mighty Asura king of Lanka. Yet though he does it to uphold the set an example that the law is equal for all, yet his love for Vydehi (daughter of Videha Janak) remains intact in its purity. Bearing the sorrow of the greatest loss at his own hands, Rama yet becomes an example in that he never marries again as was not unusual for kings. In the greatest of democratic spirit, Rama does not rule the kingdom he has conquered nor loot it’s gold but crowns Vibhishan, the brother of Ravan as the king of Lanka. Free from hatred, ambition, fear and jealousy Rama asks Laksman to learn about good governance from his enemy Ravan as he falls to the arrows of Rama. In the killing of Vali, the titanic Vanara, he keeps his promise given to his friend Sugriva while also upholding Dharma by making him the rightful king of Kiskindha rather than swallow the kingdom as part of Coshala whose capital Ayudhya was. His dealings with the ferryman Nishad, the lowly born Jatayu, the apelike humanity, all of whom he embraces and showers the love of an equal are exemplary of the highest socialistic ideals based on the equality as conceived by Vedanta. Yet this equality does not swerve him from rendering justice as per the demand of the dharma of the Age to maintain the social order as we find in the stories of the killing of Sambhook, the outcaste engaged in tapasya to gain powers to disturb the balance of creatures, and of Tadaka, the ogre woman threatening the yagyas.

Sri Aurobindo summarises his life and work beautifully and quite comprehensively in some of his letters written in response to a modern criticism:

‘….an Avatar is not at all bound to be a spiritual prophet—he is never in fact merely a prophet, he is a realiser, an establisher—not of outward things only, though he does realise something in the outward also, but, as I have said, of something essential and radical needed for the terrestrial evolution which is the evolution of the embodied spirit through successive stages towards the Divine. It was not at all Rama’s business to establish the spiritual stage of that evolution—so he did not at all concern himself with that. His business was to destroy Ravana and to establish the Ramarajya—in other words, to fix for the future the possibility of an order proper to the sattwic civilised human being who governs his life by the reason, the finer emotions, morality or at least moral ideals, such as truth, obedience, cooperation and harmony, the sense of humour, the sense of domestic and public order, to establish this in a world still occupied by anarchic forces, the Animal Mind and the powers of the vital Ego making its own satisfaction the rule of life, in other words, the Vanara and the Rakshasa. This is the meaning of Rama and his life-work and it is according as he fulfilled it or not that he must be judged as Avatar or no Avatar. It was not his business to play the comedy of the chivalrous Kshatriya with the formidable brute beast that was Bali, it was his business to kill him and get the Animal Mind under his control. It was his business to be not necessarily a perfect, but a largely representative sattwic Man, a faithful husband and lover, a loving and obedient son, a tender and perfect brother, father, friend—he is friend of all kinds of people, friend of the outcaste Guhaka, friend of the Animal leaders, Sugriva, Hanuman, friend of the vulture Jatayu, friend even of the Rakshasa Vibhishan. All that he was in a brilliant, striking but above all spontaneous and inevitable way, not with a forcing of this note or that like Harishchandra or Shivi, but with a certain harmonious completeness. But most of all, it was his business to typify and establish the things on which the social idea and its stability depend, truth and honour, the sense of the Dharma, public spirit and the sense of order. To the first, to truth and honour, much more even than to his filial love and obedience to his father—though to that also—he sacrificed his personal rights as the elect of the King and the Assembly and fourteen of the best years of his life and went into exile in the forests. To his public spirit and his sense of public order (the great and supreme civic virtue in the eyes of the ancient Indians, Greeks, Romans, for at that time the maintenance of the ordered community, not the separate development and satisfaction of the individual was the pressing need of human evolution) he sacrificed his own happiness and domestic life and the happiness of Sita. In that he was at one with the moral sense of all the antique races, though at variance with the later romantic individualistic sentimental morality of the modern man who can afford to have that less stern morality just because the ancients sacrificed the individual in order to make the world safe for the spirit of social order. Finally it was Rama’s business to make the world safe for the ideal of the sattwic human being by destroying the sovereignty of Ravana, the Rakshasa menace. All this he did with such a divine afflatus in his personality and action that his figure has been stamped for more than two millenniums on the mind of Indian culture and what he stood for has dominated the reason and idealising mind of man in all countries—and in spite of the constant revolt of the human vital is likely to continue to do so until a greater Ideal arises. And you say in spite of all this that he was no Avatar? If you like—but at any rate he stands among the few greatest of the great Vibhutis. You may dethrone him now—for man is no longer satisfied with the sattwic ideal and is seeking for something more—but his work and meaning remain stamped on the past of the earth’s evolving race.‘ (Sri Aurobindo, Letters on Rama as Avatar3)

We can safely conclude that Rama represents the soul of ancient India known then as Aryavarta. Sri Aurobindo helps us inder that the Aryan was not a conqueror from outside but a high psychological conception of an ideal human being. This high psychological type is yet to be acquired by much of humanity. All the more therefore it is imperative to remember Rama and the spiritual and psychological inheritance he has left for mankind. He may not be perfect in every sphere, – which human birth has been, yet his life and ideals of noble conduct set a high benchmark as steps upon a great ladder of ascension through which man climbs towards the future superhumanity that we see presaged in Sri Krishna and summarised in Sri Aurobindo. Yet Rama helps us in surpassing the Vanara and the Asura by subduing these tendencies by the force of moral and ethical nature. Once we do that we are ready for going beyond the dualities that the Gita preaches in a practical dynamic way. First the true human out of the animal and then the superhuman by surpassing the highest limits of an illumined Reason into the plenary light of the Supramental intuition.

A temple dedicated to Rama is not only a reminder of the great ancient past but a reconnecting of our present with the soul of India to draw nourishment and strength for the future. That it should be built in the place of his birth is not only a befitting tribute to the heroic soul of India that Rama symbolises but also the sign that India is rising not only as another economically and militarily strong nation but as a pall bearer of Sanatan Dharma that alone can redeem humanity from its present chaos into which it has plunged. Ancient India knew the importance of special power spots that bore the stamp of mighty memories. Though the cities get buried with the March of civilization yet the vibration remains alive forever and those who can attune themselves through faith and aspiration, devotion and surrender can still feel it calling us to sublime heights. Herein lies the importance of the place, the spot where the temple is being built.

In the closing we can say that the destruction of the temple by the barbaric invaders from the western mountain pass was the symbol of a period of eclipse beginning in the glory of India. The sun of India that had arisen with the Solar Dynasty and kept glowing through the centuries with its legendary heroes and sages and seers and kings and Vibhutis and Avatars was slowly eclipsed, though never totally lost to sight, with the dark period of invasions. The reconstruction of the temple, on the other hand, is the sign that, – to paraphrase Sri Aurobindo, the sun of India’s destiny is rising and shall overflow Asia and overflow the World. It is India that can show the world the way to the future but for that it is important that Indians must first recover their own lost wisdom and strength. Let me close with these words of Sri Aurobindo showing us the way:

‘We say to the individual and especially to the young who are now arising to do India’s work, the world’s work, God’s work, “You cannot cherish these ideals, still less can you fulfil them if you subject your minds to European ideas or look at life from the material standpoint. Materially you are nothing, spiritually you are everything. It is only the Indian who can believe everything, dare everything, sacrifice everything. First therefore become Indians. Recover the patrimony of your fore-fathers. Recover the Aryan thought, the Aryan discipline, the Aryan character, the Aryan life. Recover the Vedanta, the Gita, the Yoga. Recover them not only in intellect or sentiment but in your lives. Live them and you will be great and strong, mighty, invincible and fearless. Neither life nor death will have any terrors for you. Difficulty and impossibility will vanish from your vocabularies. For it is in the spirit that strength is eternal and you must win back the kingdom of yourselves, the inner Swaraj, before you can win back your outer empire. There the Mother dwells and She waits for worship that She may give strength. Believe in Her, serve Her, lose your wills in Hers, your egoism in the greater ego of the country, your separate selfishness in the service of humanity. Recover the source of all strength in yourselves and all else will be added to you, social soundness, intellectual pre-eminence, political freedom, the mastery of human thought, the hegemony of the world.’ (Sri Aurobindo, The Ideals of the Karmayogin)4)