An essay and a poem, written by Rabindranath Tagore following his meeting with Sri Aurobindo in May 1928.

FOR a long time I had a strong desire to meet Aurobindo Ghosh, It has just been fulfilled. I feel that I must write down the thoughts that have come to my mind. In the Christian Scripture it has been said:—”In the beginning,there was the Word.” The Word takes form in creation. It is not the calendar which introduces a new era. It is the Word leading man to the path of a higher manifestation, a richer reality.

In the beginning and end of all great utterances in our scriptures we have the word Om. It has the meaning of self acknowledgement of Truth, it is the breath of the Eternal.

From some great sea of idea, a tidal wave tumultuously broke upon Europe carrying on its crest the French Revolution. It was a new age, not because the oppressed of that time in France stood against their oppressors, but because that age had in its beginning the Word which spoke of a great moral liberation for all humanity.

Mazzini and Garibaldi ushered in a new age of awakening in Italy, not because of the external fact of a change in the political condition of that country, but because they gave utterance to the Word, which did not merely enjoin formal acts, but inspired an inner creative truth. The feeling of touch, with the help of which a man gathers in darkness things that are immediate to him, exclusively belongs to himself; but the sunlight represents the great touch of the universe; it is for the needs of every one, and it transcends the needs of all individuals. This fight is the true symbol of the Word.

One day science introduced a new age to the Western world, not because she helped man to explore nature’s secrets, but because she revealed to him the universal aspect of reality in which all individual facts find their eternal background, because she aroused in him the loyalty to truth that could defy torture and death. Those who follow the modern development of science know that she has truly brought us to the threshold of another new age, when she takes us across things to the mystic shrine of light where sounds the original Word of Creation.

In ancient India, the age of creation began with the transition from ritual practices to spiritual wisdom. It sent its call to the soul, which creates from its own abundance; and men woke up and said, that only those truly live, who live in the bosom of the Eternal. This is the Word spoken from the heart of that age : “Those who realise Truth, realise immortality.”

In the Buddhist age, also, the Word came with the message of utmost sacrifice, of a love that is unlimited. It inspired an ideal of perfection in man’s moral nature, which busied itself in creating for him a world of emancipated will.

The Word is that which helps to bring forth towards manifestation the unmanifest immense in man. Nature urges animals to restrict their endeavour in earning their daily wages of living. It is the Word which has rescued man from that enclosure of a narrow livelihood to a wider freedom of life. The dim light in that world of physical self-preservation is for the world of night; and men are not nocturnal beings. Time after time, man must discover new proofs to support the faith in his own greatness, the faith that gives him freedom in the Infinite. It is realised anew every time that we find a man whose soul is luminously seen through the

translucent atmosphere of a perfect life. Not the one who has the strength of an intellect that reasons, a will that plans, the energy that works, but he whose life has become one with the Word, from whose being is breathed Om, the response of the everlasting yes.

The longing to meet such a person grows stronger when we find in men around us the self-mistrust which is spiritual nihilism, producing in them an indecent pride in asserting the paradox that man is to remain an incorrigible brute to the end of his days, that the value of our ideals must be judged by a standard which is that of the market price of things.

When, as today, truth is constantly being subordinated to purposes that have their sole meaning in a success hastily snatched up from a mad scramble for immediate opportunities our greed becomes uncontrollable. In its impatience it refuses to modulate its pace to the rhythm that is inherent in a normal process of achievement, and exploits all instruments of reckless speed, including propaganda of delusion. Ambition tries to curtail its own path, for its gain is at the end of that path, while truth is permeatingly one with the real seeking for her, as a flower with its stem. But, used as a vehicle of some utility, robbed of her love’s wooing, she departs, leaving that semblance of utility a deception.

Ramachandra, the hero of the great epic Ramayana, during the long period of his wanderings in the wilderness, came to realise, helped by constant difficulties and dangers, the devotion of his wife Sita, his companion in exile. It was the best means of gaining her in truth through a strenuously intimate path of ever-ripening experience. After his return to his kingdom, urged by an immediate political necessity, he asked Sita to give an instant proof of her truth in a magic trial by fire before the suspicious multitude. Sita refused, knowing that such a trial could only offend truth by its callous unreality, and she disappeared for ever.

It brings to my mind the opening line of an old Bengali poem which my friend Kshitimohan Sen offered to me from his rich store of rare sayings. It may be translated thus: “O cruel man of urgent needs, Must thou in thy haste scorch by fire the mind that is still in bud ?”

It takes time to prove the spirit of perfection lying in wait in a mind that is yet to mature. But a cruel urgency takes the quick means of a forced trial and the mind itself disappears leaving the crowd to admire the gorgeousness of the preparation. When we find everywhere the hurry of this greed dragging truth tied to its chariot-wheels along the dusty delusion of short-cuts, we feel sure that it would be futile to set against it a mere appeal of reason, but that a true man is needed who can maintain the patience of a profound faith against a constant temptation of urgency and hypnotism of a numerical magnitude.

We badly need today for the realisation of our human dignity a person who will preach respect for man in his completeness. It is a truism to say that man is not simple, that his personality consists of countless elements that are bewilderingly miscellaneous. It is possible to denude him of his wealth of being in order to reduce him to a bare simplicity that helps to fit him easily to a pattern of a parsimonious life. But it is important to remember that man is complex, and therefore his problems can only be solved by an adjustment, and not by any suppression of the varied in him or by narrowing the range of his development. By thinning it to an unmeaning repetition, eliminating from it the understanding mind and earnestness of devotion we can make our prayer simple and still simpler by bringing it down to a mechanical turning of the prayer wheel as they have done in Tibet. Such a process lightens the difficulty of a work by minimising the humanity of the worker. Teachers who are notoriously successful in guiding their pupils through examinations know that teaching can be made simple by cramming and hushing the questioning mind to sleep. It hastens success through a ruthless retrenchment of education.

The present-day politics has become a menace to the world, because of its barbarous simplicity produced by the exclusion of the moral element from its method and composition. Industrialism also has its cult of an ascetic miserliness that simplifies its responsibility by ignoring the beautiful. On the other hand, the primitive methods of production attain their own simplicity through a barren negation of science and, to that extent, a poor expression of humanity. We recognise our true teacher when he comes not to lull us to a minimum vitality of spirit but to rouse us to the heroic fact that man’s path of fulfilment is difficult, “durgam pathas tat.” Animals drifting on the surface of existence have their life that may be compared to a simple raft composed of banana trunks held together. But human life finds its symbol in a perfectly modelled boat which has its manifold system of oars, helm and sails, towing ropes and poles for the complex purpose of negotiating with the three elements of water, earth and air. For its construction it claims from science a principle of balance based upon countless observations and experiments, and from our instinct for art the decorations that are utterly beside the purpose with which they are associated. I t gives expression to the intelligent mind which is carefully accurate in the difficult adjustment of various forces and materials and to the creative imagination that delights in the harmony of forms for its own sake. We should never be allowed to forget that spiritual perfection comprehends all the riches of life and gives them a great unity of meaning.

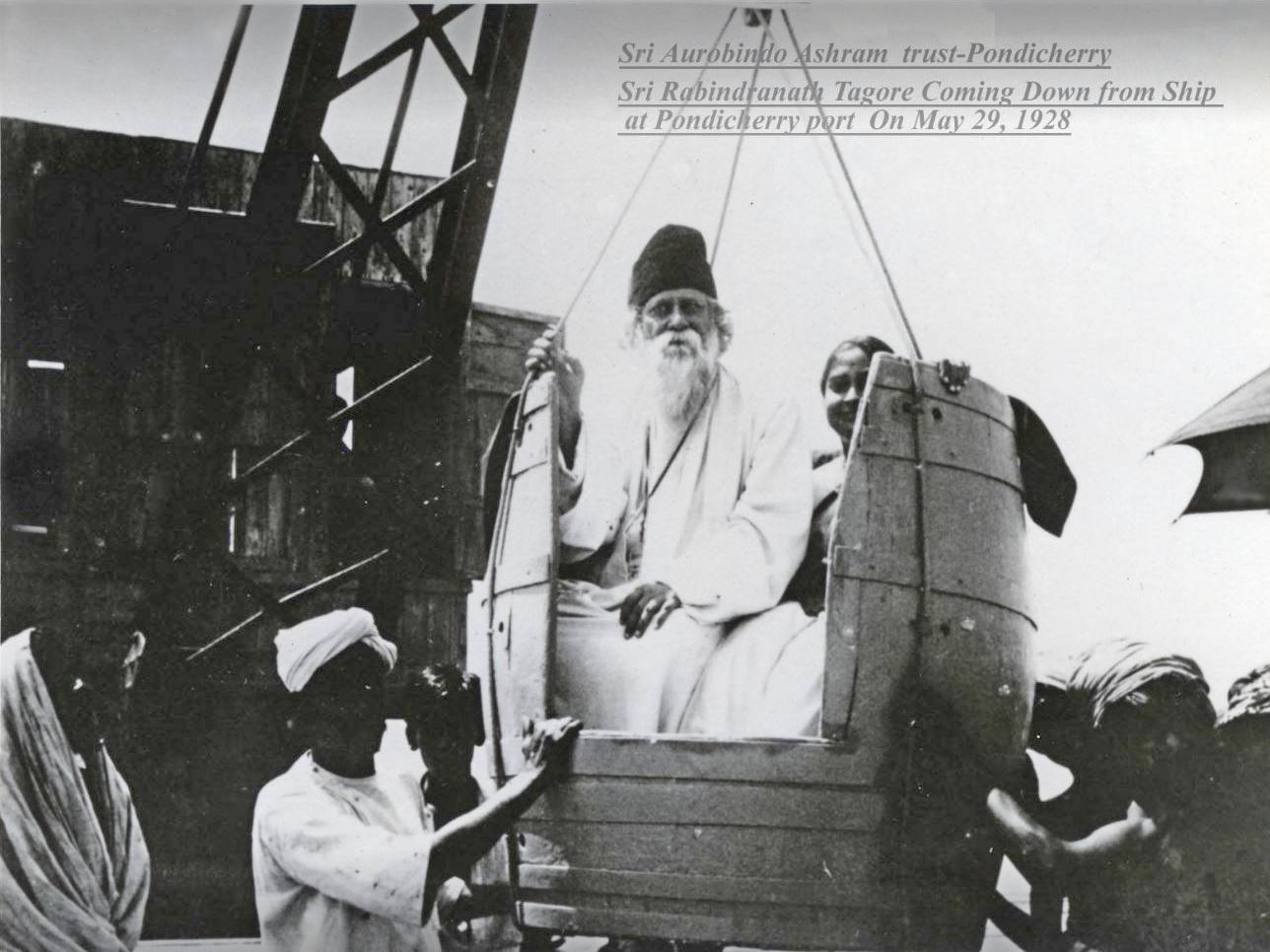

While my mind was occupied with such thoughts, the French steamer on which I was travelling touched Pondicherry and I came to meet Aurobindo. At the very first sight I could realise that he had been seeking for the soul and had gained it, and through this long process of realisation has accumulated within him a silent power of inspiration. His face was radiant with an inner light and his serene presence made it evident to me that his soul was not crippled and cramped to the measure of some tyrannical doctrine, which takes delight in inflicting wounds upon life. He, I am sure, never had his lessons from the Christian monks of the ascetic Europe, revelling in the pride of that self-immolation which is a twin sister of self-aggrandisement joined back to back facing opposite directions.

I felt that the utterance of the ancient Hindu Rishi spoke from him of that equanimity which gives the human soul its freedom of entrance into the All.

I said to him, “You have the Word and we are waiting to accept it from you. India will

speak through your voice to the world, ‘Hearken to me’.”

In her earlier forest home Sakuntala had her awakenment of life in the restlessness of her youth. In the later hermitage she attained the fulfilment of her life.

Years ago I saw Aurobindo in the atmosphere of his earlier heroic youth and I sang to him,

“Aurobindo, accept the salutation from Rabindranath.”

Today I saw him in a deeper atmosphere of a reticent richness of wisdom and again sang to him in silence, “Aurobindo, accept the salutation from Rabindranath.”

S. S. Chantilly,

May, 29, 1928.

(Published in The Modern Review in July 1928).

SALUTATION

RABINDRANATH, O Aurobindo, bows to thee !

O friend, my country’s friend, O voice incarnate, free,

Of India’s soul ! No soft renown doth crown thy lot,

Nor pelf or careless comfort is for thee; thou’st sought

No petty bounty, petty dole; the beggar’s bowl

Thou ne’er hast held aloft. In watchfulness thy soul

Hast thou e’er held for bondless full perfection’s birth

For which, all night and day, the god in man on earth

Doth strive and strain austerely; which in solemn voice

The poet sings in thund’rous poems ; for which rejoice

Stout hearts to march on perilous paths; before whose flame

Refulgent, ease bows down its head in humbled shame

And death forgetteth fear;—that gift supreme

To thee from Heaven’s own hand, that full-orb’d fadeless dream

That’s thine, thou’st asked for as thy country’s own desire

In quenchless hope, in words with truth’s white flame afire,

In infinite faith, hath God in heaven heard at last

This prayer of thine? And so, sounds there, in blast on blast,

His victory-trumpet ? And puts he, with love austere,

In thy right hand, today, the fateful lamp and drear

Of sorrow, whose light doth pierce the country’s agelong gloom,

And in the infinite skies doth steadfast shine and loom,

As doth the Northern star ? O Victory and Hail!?

Where is the coward who will shed tears today, or wail

Or quake in fear ? And who’ll belittle truth to seek

His own small safety ? Where’s the spineless creature weak

Who will not in thy pain his strength and courage find ?

O wipe away those tears, O thou of craven mind !

The fiery messenger that with the lamp of God :

Hath come—-where is the king -who can with chain or rod

Chastise him ? Chains that were to bind salute his feet.

And prisons greet him as their guest with welcome sweet,

The pall of gloom that wraps the sun in noontide skies

In dim eclipse, within a moment slips and flies

As doth a shadow. Punishment ? It ever falls

On him who is no man, and every day hath feared,

Abashed, to gaze on truth’s face with a free man’s eye

And call a wrong a wrong; on him who doth deny

His manhood shamelessly before his own compeers,

And e’er disowns his God-given rights, impelled by fears

And greeds; who on his degradation prides himself,

Who traffics in his country’s shame; whose bread, whose pelf

Are his own mother’s gore; that coward sits and quails

In jail without reprieve, outside all human jails.

When I behold thy face, ‘mid bondage, pain and wrong

And black indignities, I hear the soul’s great song

Of rapture unconfined, the chant the pilgrim sings

In which exultant hope’s immortal splendour rings,

Solemn voice and calm, and heart-consoling, grand

Of imperturbable death, the spirit of Bharat-land,

O poet, hath placed upon thy face her eyes a fire

With love, and struck vast chords upon her vibrant lyre,—

Wherein there is no note of sorrow, shame or fear,

Or penury or want. And so today I hear

The ocean’s restless roar borne by the stormy wind,

Th’ impetuous fountain’s dance riotous, swift and blind

Bursting its rocky cage,—the voice of thunder deep

Awakening, like a clarion call, the clouds asleep

Amid this song triumphant, vast, that encircles me,

Rabindranath, O Aurobindo, bows to thee !

And then to Him I bow Who in His sport doth make

New worlds in fiery dissolution’s awful wake,

From death awakes new life; in danger’s bosom rears.

Prosperity; and sends his devotee in tears,

‘Mid desolation’s thorns, amid his foes to fight

Alone and empty-handed in the gloom of night;

In divers tongues, in divers ages speaketh ever

In every mighty deed, in every great eendeavour

And true experience: “Sorrow’s naught, howe’er drear

And pain is naught, and harm is naught, and naught all fear;

The king’s a shadow, – punishment is but a breath;

Where is the tyranny of wrong, and where is death ?

0 fool, O coward, raise thy head that’s bowed in fear,

I am, thou art, and everlasting truth is here.”

RABINDRANATH TAGORE

Published in Sri Aurobindo Mandir Annual 1944

Translated from original Bengali by Kshitishchandra Sen