SRI AUROBINDO

Collected Plays and Short Stories

Part Two

or Love Shuffles the Cards

A Comedy

Cupid

Ate

King Philip of Spain

Count Beltran, a nobleman.

Antonio, his son.

Basil, his nephew.

Count Conrad, a young nobleman.

Roncedas,

Guzman, Courtiers.

The Miller.

Acinto, his son.

Jeronimo, a student.

Carlos, a student.

Friar Baltasar, a pedagogue.

Euphrosyne, the maid of the farm.

Ismenia, sister of Conrad.

Brigida, her cousin.

Scene I

The King’s Court at Salamanca.

King Philip, Conrad, Beltran, Roncedas, Guzman, Antonio, Basil, Ismenia, Brigida, Grandees.

Count Beltran.

It is no secret, Sire. And yet so little5

This toy is mine, the name’s far off from me.

Castilians, forgèd iron of old time

Armies to wield and empires, we’re astray6

With these smooth, silken things. We were never valiant

Vega with Calderon to weigh and con

Devices. But our sons, Sire, have outstripped

Their rough begetters, almost they are Frenchmen.

Of Paris and the Rape of Spartan Helen.

Antonio?

O my poor eyes misled,

O my poor eyes misled,

Whither have you wandered?

The fitter for a masque that’s heard but once.14

For15 the swift action of the stage speeds on

And16 slow conception labouring after it

Roughens its subtleties, blurs o’er its17 shades,

Sees masses only. Then if18 the plot is new,

The mind engrossed with incidents, omits19

To take the breath of flowers and lingering shade

In hurrying with the stream.20 But the plot known21,

It is at leisure and may cull in running22

Those delicate, scarcely-heeded strokes, which lost23

Perfection’s disappointed. There art comes in24

To justify genius. Being old besides25

The subject occupies26 creative labour

To make old new. The other’s but invention,27

A frail thing28, though a gracious. He’s creator

Who greatly handles great material,

Calls order out of the abundant deep,

Not who invents sweet shadows out of air.

Pardon, Sir, I forgot my limits thus29

To speak at random in so great a presence.

You have a hopeful son, Lord Beltran, modest30

And witty, a fair conjunction, a large critic

And taking speaker.

My heart out of my bosom.

My heart out of my bosom.

Will you hush?

Count, I have heard your lands are very lavish31

In Nature’s best. I think I have not seen them.32

Indeed I grudge each rood of Spanish earth

My eyes have not perused, my heart stored up.

Yet33 what with foreign boyhood, strange extraction

And hardly reaching with turmoil to power

I am a stranger purely34. I have swept

Through beautiful Spain more like a wind than man,

Now fugitive, now blown into my right

On a mere35 whirlwind of success. But maybe36

Great occupation has disabled you37

From this poor trifle also.

My son would answer better, Sire. I care not

Whether this tree be like a tower or that

A dragon: and I never saw myself

Difference twixt field and field, save the main one

Of size, boundary and revenue; and those

Were great once,— why now lessened and by whom

I will not move you by repeating, Sire,

Although my heart speaks of it feelingly.

Speak39 then, Antonio, but tell me not

Of formal French demesnes and careful parks,

Life dressed like a stone lady, statuesque,

They please the judging eye, but not the heart.

When Nature is disnatured, all her glowing

Great outlines chillingly disharmonised

Into stiff lines, the heart’s dissatisfied,

Into stiff lines, the heart’s dissatisfied,

Asks freedom, wideness, it compares the sweep

Of the large heavens above and feels a discord.

Your architects plan beauty by the yard,

Weigh sand with sand, parallel line with line

But miss the greatest. Since uncultured force

Though rude, yet striking home, by far exceeds

Artisan’s work, mechanically good.

Our fields, Sire40, are a rural holiday,

Not Nature carved?

Has she a voice to you?

Yes, we have brooks

Muttering through sedge and stone, and willows by them

Leaning dishevelled and forget-me-nots,

Wonders of lurking azure, rue and mallow,

Honeysuckle and painful meadowsweet,

And when we’re tired of watching the rich bee

Murmur absorbed about one lonely flower

Then we can turn and hear a noon of birds.

Each on his own heart’s quite intent, yet all

Join sweetness at melodious intervals.

You have many trees?

Glades, Sire, and green assemblies

And separate giants bending to each other

As if they longed to meet. Some are pranked out,

Others wear merely green like foresters.

Can hatred sound so sweet? Are enemies’ voices

Like hail of angels to the ear, Brigida?

Hush, fool. We are too near. Someone will mark you.

Why, cousin, if they do, what harm? Sure all

Unblamed may praise sweet music when they hear it.

Rule your tongue, madam. Or must I leave you?

You have made me sorrowful. How different

Is this pale picture of a Court, these walls

Shut out from honest breathing; God kept not

His quarries in the wild and distant hills

For such perversion. It was sin when first

Hands serried stone with stone. Guzman, you are

A wise, a patient41 reasoner,— is it not better

To live in the great air God made for us,

A peasant in the open glory of earth,

Feeling it, yet not knowing it, like him

To drink the cool life-giving brook nor crave

The sour fermented madness of the grape

Nor the dull exquisiteness of far-fetched viands

For the tired palate, but black bread or maize,

Mere wholesome ordinary corn. Think you not

A life so in the glorious sunlight bathed,

Straight nursed and suckled from the vigorous Earth

With shaping labour and the homely touch

Of the great hearty mother, edifies

A nobler kind than nourished is in Courts?

But42 we are even as children quite43 removed

From those her streaming breasts, and44 of the sun

Defrauded and the lusty salutation

Defrauded and the lusty salutation

Of wind and rain, grow up amphibious nothing,

Non-man45, who are too sickly wise for earth

And too46 corrupt to be the47 heirs of heaven.

I think not so, Your Highness.

Not so, Guzman?

Is not a peasant happier than a king?

For he has useful physical toil and sleep

Unbroken as a child’s. He is not hedged

By swathing ceremony which forbids

A king to feel himself a man. He has friends,

For he has equals. And in youth he marries

The comrade of his boyhood whom he loved

And gets on that sweet helper stalwart children,

Then brings his grandchildren climbing on his knees,48

A happy calm old man; because he lived

Man’s genuine life and goes with task accomplished

Thro’ death as thro’ a gate, not questioning.

Each creature labouring in his own vocation

Desires another’s and deems the heavy burden

Of his own fate the world’s sole heaviness.

Each thing’s to its perceptions limited,

Another’s are to it intangible,

A shadow far away, quite bodiless,

Lost in conjecture’s wide impalpable.

On its unceasing errand through the void

The earth rolls on, a blind and moaning sphere.

It knows not Venus’ sorrows, but it looks

With envy crying, “These have light and beauty,

I only am all dark and comfortless.”

The land yearning for life, endeavours seaward,

The sea, weary of motion, pines to turn

The sea, weary of motion, pines to turn

Into reposeful earth: yet were this done

Each would repine again and hate the doer;

The land would miss its flowers and grass and birds,

The sea long for the coral and the cave.

For he who made labour the base49 of life,

Gave with it power, a thing so dear to existence,50

To lose’t is death. Toil is the form of power;

Nay, toil’s self creates answering energy

And makes the loss of toil a wretchedness.

The labourer physically is divine,

Inward a void, yet in his limits blest.

But were the city’s cultured son, who turns

Watching an51 envious, crying “Were I simple,

Primeval in my life as he, how happy!”,

Into such environs confined, how then

His temperament would beat against the bars

Of circumstance and rage for wider field.

Uninterchangeable their natures stand

And self-confined; for so Earth made them, Earth,

The brute and kindly mother groping for mind.

She of her vigorous nature bore her sons

Made lusty with her milk and the warm force52

Redundant in her veins, else like the lark53

Aiming from her to heaven. And souls are there

Who rooted in her puissant animalism

Are greatly earthy, yet widen to the void54

And heighten to the sky55. But these are rare

And of no privileged country citizens

Nor to the city bounded nor the field.

They are wise and royal in the furrow, keep

In schools their chastened vigour from the soil

To base their spirits vastly. Man is strong56

Antaeuslike, based on his native Earth

From which being lifted great communities

Die in their intellectual grandeur. So57 then

Let the soil’s son and grafting of the city58

Keep their conditions, heightened or refreshed

Keep their conditions, heightened or refreshed

With59 breath and force of each a different spirit

If may be; one not admit untutored envy

The other vain imagination making

Return to nature a misleading name

For a reversion most unnatural.

You reason well, Guzman; nor must we pine

At stations where God and his saints have set us.

And yet because I’d60 feel the rural air,

Of greatness unreminded, I will go

Tomorrow as a private nobleman.61

My lords, forget for one day I’m the king

Nor watch my moods, nor with your eyes wait on me

Nor disillusionize by high62 observance

But keep as to an equal courtesy.

But, Your63 Majesty —

Well, Sir, Your Ancient Wisdom —

The Kings of Spain —

Are absolute, you’ld say,

Over men only? Custom masters kings.

I’ll not be ruled by your stale ceremonies

As kings are by an arrogating Senate,

But will control them, wear them when I will,

Walk disencumbered when I will. Enough

You have done your part in protest. I have heard you.

Your Highness is obeyed.

Tell on, Antonio, who perform the masque.

That can I tell Your Highness, rural girls,

The daughters of the soil, whom country air

Has given the ruddy64 health to bloom in their cheeks65.

Full of our Spanish sunlight are they, voiced

Like Junos and will make our ladies pale

Before them. There’s a Miller’s66 lovely daughter,

A marvel. Robed in excellent apparel

As she will be, there’s not a maid in Spain

Can stand beside her and stay happy. My sons

Have spared nor words nor music nor array

Nor beauty to express their loyal duty.

I am much graced by this their gentle trouble

And yet, Lord Beltran, there are nobler things

Than these brocaded masques, not that I scorn these,

Do not believe I would be so ungracious,—

Nor anything belittle in which true hearts

Interpret their rich silence. Yet there’s one

Desire, I would exchange for many masques,

’Tis noble67: an easy word bestows it wholly,

And yet, I fear, for you too difficult.

My lord, you know my service and should not

Doubt my compliance. Name and take it. Else judge me.

Why, noble reconcilement, Conde Beltran;

Sweet friendship between mighty jarring houses

And by great intercession war renounced

And by great intercession war renounced

Betwixt magnificent hearts: these are the masques

Most sumptuous, these the glorious theatres

That subjects should present to princes. Conrad

And noble Beltran, I respect the wrath

Sunders your pride: yet mildness has the blessing

Of God and is religion’s perfect mood.

Admit that better weakness. Throw your hearts

Wide to the knocks68 of entering peace: let not

The ashes of a rage the world renounces

Smoulder between you nor outdated griefs

Keep living. What, quite silent? Will you, Conrad,

Refuse to me your answer69, who so often

Have for my sake your very life renounced?

My lord, the hate that I have never cherished

I know not how to abandon. Not in the sway

Of other men’s affections I have lived

But walked in the straight road my fortunes build me.

Let any love who will or any hate who will,

I take both with a calm, unburdened spirit,

Inarm my lover as a friend, embrace

My enemy as a wrestler: do my will,

Because it is my will, go where I go,

Because my path lies there. If any cross me,

That is his choice, not mine. And if he suffer,

Again it is his choice, not mine. It’s70 I,

That is my star. I curse him not for it:

My fate’s beyond his making as my spirit’s

Above affection by him. I hate no man,

And if Lord Beltran give to me his hand,

I will most gladly clasp it and forget71

Outdated injuries and wounds long healed.

O you72 are most noble, Conrad, most benign.

Who now can say the ill-doer ne’er forgives?

Who now can say the ill-doer ne’er forgives?

Conrad has dispossessed my kinsmen, slain

My vassals, me of ancient lands relieved,

Thinned my great house; but Beltran is forgiven.

Will you not now enlarge your generous nature,

Wrong me still more, have new and ampler room

For exercise to your forgiving heart,

I must73 embrace misfortune and fresh loss

Before your friendship, lord.

No more of this.

Pardon, Your Highness; this was little praise

For so deep74 Christianity. Lord Conrad,

I will not trouble you further. And perhaps

With help of the good saints and holy Virgin

I too shall make me some room to pardon in.

I fear you not, Lord Count. Our swords have clashed:

Mine was the stronger. For what I have won75,

I got it by decree of arms. So you

Had won mine, had you taken sides with fortune

And kept her faithful with your sword. Your satire

Has no sharp edge till it cut that from me.

This is unprofitable. No more of it.

Lord Conrad, you go homeward with the dawn?

Winning your gracious leave to have with me

My sisters, Sir.

The Queen is very loth

To lose her favourite76, but to disappoint you

Much more unwilling. You’ll come with me,77

My lords, you too, Lord Beltran.

Exeunt King, Beltran, Guzman and Grandees.

A word, with you Lord Conrad.

As many as you will, Roncedas.

My lord, your good friend always.

So you have been.

Cousin, and sweetest sister, I am bound

Homeward upon a task that needs my presence.

Don Mario and his wife will bring you there.

Are you content or shall I stay for you?

With all you do, dear brother, yet would have

Your blessing by me.

May your happiness

Greatly exceed my widest wishes.78

So

It must do, brother or I am unhappy.79

What task will he have now? Some girl-lifting.80

What other task!81 Shall we go, cousin?

Stay.

Let us not press so closely after them.

Good manners? Oh, your pardon. I was blind.

Are you a lover or a fish,82 Antonio?

Speak?

The devil remove you

Where you can never more have sight of her.

Cousin, I know you’re tired

With standing. Sit, and if you tire with that,

As perseverance is a powerful virtue,

For your reward the dumb may speak to you.

What shall I do, dear girl?

Why, speak the first,

Count Conrad’s sister! Be the Mahomet

To your poor mountain. Hang me if I think not

The prophet’s hill more moveable of the two;

The prophet’s hill more moveable of the two;

An earthquake stirs not this. What ails the man?

He has made a wager with some lamp-post surely.

Brigida, are you mad? Be so immodest?

A stranger and my house’s enemy!

No, never speak to him. It would be indeed

Horribly forward.

Why, you jest, Brigida.

I’m no such light thing that I must be dumb

Lest men mistake my speaking. Let frail men83

Or men suspect to their own purity

Guard every issue of speech and gesture. Wherefore

Should I be hedged so meanly in? To greet

With few words, cold and grave, as is befitting

This gentle youth, why do you call immodest?

You must not.

I say

You must not, child.

I will then, not because

I wish (why should I?), but because you always

Provoke me with your idle prudities.

Good! You’ve been wishing it the last half-hour

And now you are provoked to’t. Charge him, charge him.

Impossible creature!

But no! You shall not turn me.

’Twas not my meaning.

Sir —

Rouse yourself, Antonio. Gather back

Your manhood, or you’re shamed without retrieval.

Help me, Brigida.

Not I, cousin.

Sir,

You spoke divinely well. I say this, Sir,

Not to recall to you that we have met —

Since you will not remember — but because

I would not have you — anyone — think this of me

That since you are Antonio and my enemy

And much have hurt me — to the heart, therefore

When one speaks or does worthily, I can

Admire not, nor love merit, whosoe’er

Be its receptacle. This was my meaning.

I could not bear one should not know this of me.

Speak or be dumb forever.

I see, you have mistook me why I spoke

And scorn me. Sir, you may be right to think

You have so sweet a tongue would snare the birds

From off the branches, ravish an enemy,

— Some such poor wretch there may be — witch her heart out,

If you could care for anything so cheap

And hold it in your hand, lost,— lost,— Oh me!

Confounded. Speak, you sheep, you!

Though this is so,

You do me wrong to think me such an one,

Most flagrant wrong, Antonio. To think that I

Wait one word of your lips to woo you, yearn

To be your loving servant at a word

From you,— one only word and I am yours.

Admirable lady! Saints, can you be dumb

Who hear this?

Still you scorn me. For all this

You shall not make me angry. Do you imagine

Because you know I am Lord Conrad’s sister

And lodge with Donna Clara Santa Cruz

In the street Velasquez, and you have seen it

With marble front and the quaint mullioned windows,

With marble front and the quaint mullioned windows,

That you need only after vespers, when

The streets are empty, stand there, and I will

Send one to you? Indeed, indeed I merit not

You should think poorly of me. If you’re noble

And do not scorn me, you will carefully

Observe the tenour of my prohibition,

Brigida.

Come away with your few words,

Your cold grave words. You have84 frozen his speech with them.

Heavens! it was she — her words were not a dream,

Yet I was dumb. There was a majesty

Even in her tremulous playfulness, a thrill

When she smiled most, made my heart beat too quickly

For speech. O that I should be dumb and shamefast,

When with one step I might grasp Paradise.

Antonio!

I was not deceived. She blushed,

And the magnificent scarlet to her cheeks

Welled from her heart an ocean inexhaustible.

Rose but outcrimsoned rose. Yes, every word

Royally marred the whiteness of her cheeks

With new impossibilities of beauty.

She blushed, and yet as with an angry shame

Of that delicious weakness, gallantly

Her small imperious head she held erect

And strove in vain to encourage those sweet lids

That fluttered lower and lower. O that but once

My tongue had been as bold as were mine eyes!

My tongue had been as bold as were mine eyes!

But these were fastened to her as with cords,

Courage in them naked necessity.

Ah poor Antonio. You’re bewitched, you’re maimed,

Antonio. You must make her groan who did this.

One sense will always now be absent from him.

Lately he had no tongue. Now that’s returned

His ears are gone on leave. Hark you, Antonio

Why do we stay here?

I am in a dream.

Lead where you will; since there is no place now

In all the world, but only she or silence.

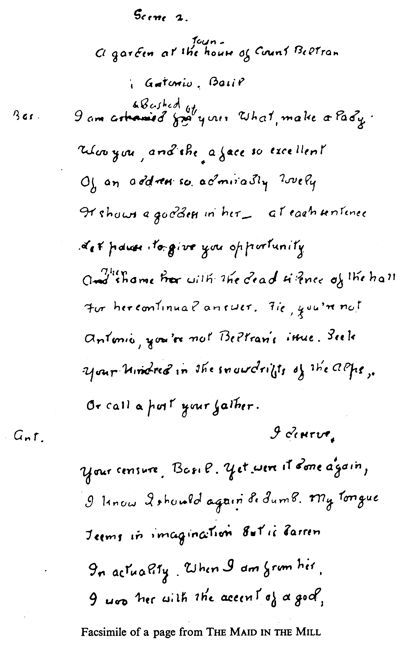

A garden at the town-house of Count Beltran.

I am abashed of85 you. What, make a lady

Woo you, and she a face so excellent,

Of an address so admirably lovely

It shows a goddess in her — at each sentence

Let pause to give you opportunity

Then shame with the dead silence of the hall

For her continual answer. Fie, you’re not

Antonio, you are86 not Beltran’s issue. Seek

Your kindred in the snowdrifts of the Alps

Or call a post your father.

I deserve

Your censure, Basil. Yet were it done again,

I know I should again be dumb. My tongue

Teems in imagination but is barren

In actuality. When I am from her,

I woo her with the accent of a god,

My mind o’erflows with words as the wide Nile

With waters. Let her but appear and I

Am her poor mute. She may do her will with me

And O remember but her words. When she,

Ah she, my white divinity with that kindness

Celestial in the smiling of her eyes

And in her voice the world’s great music, rose

Of blushing frankness, half woman and half angel,

Crowned me unwooed, lavished on me her heart

In her prodigious liberality,

Could I then speak? O to have language then

Had been the index to a shallow love.

Away! You modest lovers are the blot

Of manhood, traitors to our sovereignty.

I’d87 have you banished, all of you, and kept

In desert islands, where no petticoat

Should enter, so the brood88 of you might perish.

You speak against the very sense of love

Which lives by service.

Flat treason! Was not man made

Woman’s superior that he might control her,

In strength to exact obedience and in wisdom

To guide her will, in wit to keep her silent,

Three Herculean labours. O were women

Once loose, they would new-deluge earth with words,

Sapiently base creation on its apex,

Logic would be new-modelled, arithmetic

Grow drunk and reason despairing abdicate.

No thunderbolt could stop a woman’s will

Once it is started.

O you speak at ease,

Loved you, you would recant this without89 small

Torture to quicken you.

I wish, Antonio, I had known your case

Earlier. I would have taught you how to love.

Come, will you woo a woman? Teach me at least

By diagram, upon a blackboard.

By diagram, upon a blackboard.

Well,

I will so, if it should hearten your weak spirits.

And now I think of it, I am resolved

I’ll publish a new Art of Love, shall be

The only Ovid memorable.

On, on! Let’s hear you.90

First, I would kiss her.

What, without leave asked?

Leave? Ask a woman leave to kiss her! Why

What was she made for else?

If she is angry?

So much the better. Then you by repetition

Convince her of your manly strength, which is

A great point gained at the outset and moreover

Your duty, comfortable to yourself.

Besides she likes it. On the same occasion

When she will scold, I’ll silence her with wit.

Laughter breaks down impregnable battlements.

Let me but make her smile and there is conquest

Won by the triple strength, horse, foot, artillery,

Of eloquence, wit and muscle. Then but remains

Pacification, with or else without

The Church’s help, that’s a mere form and makes

The Church’s help, that’s a mere form and makes

No difference to the principle.

There should be

Inquisitions for such as you. What after?

Nothing unless you wish to assure the conquest,

Not plunder it merely like a Tamerlane.

I’ll teach that also. ’Tis but making her

Realise her inferiority.

Unanswerably and o’erwhelmingly

Show her how fortunate she is to get you

And all her life too short for gratitude;

That you have robbed her merely for her good,

To civilize her or to train her up:

Punish each word that shows want of affection.

Plague her to death and make her thank you for it.

Accustom her to sing hosannas to you

When you beat her. All this is ordinary,

And every wise benevolent conqueror

Has learnt the trick of it. Then she’ll love you for91 ever.

You are a Pagan and would burn for this

If Love still kept his Holy Office.

Am92 safe from him.

And therefore boast securely

Conducting in imagination wars

That others have the burden of. I’ve seen

The critical civilian in his chair

Win famous victories with wordy carnage,

Guide his strategic finger o’er a map,

Guide his strategic finger o’er a map,

Cry “Eugene’s fault! here Marlboro’93 was to blame,

And look, a child might see it, Villars’ plain error

That lost him Malplaquet!” I think you are

Just such a pen-and-paper strategist.

Death, I will have pity on you,

Antonio. You shall see my great example

And learn by me.

Good, I’m your pupil. But hear,

A pretty face or I’ll not enter for her,

Wellborn or I shall much discount your prowess.

Agreed. And yet they say experimentum

In corpore vili. But I take your terms

Lest you substract me for advantages.

Look where the enemy comes. You are well off

If you can win her.

A rare face, by Heaven.

Almost too costly a piece of goods for this

Mad trial.

You sound retreat?

Not I an inch.

Hush, she’s here.

Señor, I was bidden to deliver this letter to you.

To me, sweetheart?

I have the inventory of you in my books94, if you be he truly. I will study it. Hair of the ordinary poetic length95, dress indefinable96, a modest address,— I think not you, Señor,— a noble manner,— Pooh, no! — a97 handsome face. I am sure not to you98, Señor.

Humph.

Well, cousin. All silent? Open your batteries, open your batteries!

Wait, wait. Ought a conqueror to be hurried? Caesar himself must study his ground before he attempts it. You will hear my trumpets instanter.

Will you take your letter, Sir?

To me then, maiden? A dainty-looking note, and I marvel much from whom it can be. I do not know the handwriting. A lady’s, seemingly, yet it has a touch of the masculine too — there is rapidity and initiative in its flow. Fair one, from whom comes this?

Why, Sir, I am not her signature; which if you will look within, there I doubt not you99 will find a solution of your difficulty100.

Here’s101 a clever woman, Antonio, to think of that, and she but eighteen or a miracle.

Well, cousin.

This Don Witty-pate eyes me strangely. I fear he will recognize102 me.

You’re ill, sir, you change colour.

Now, by Heaven

Were death within my heart’s door or his blast

Upon my eyelids, this would exile him.

Sir, you pale

Extremely. Is there no poison in that103 letter?

O might I so be poisoned hourly. Let me

No longer dally with my happiness,

Let104 it take wings or turn a dream. Hail, letter,

For thou hast come from that white hand I worship.

For thou hast come from that white hand I worship.

Señor, how you may deem of my bold wooing,

How cruelly I suffer in your thoughts,

I dread to think. Take the plain truth, Antonio.

I cannot live without your love. If you

From this misdoubt my nobleness or infer

A wanton haste or instability,—

As men pretend quick love is quickly spent —

Tear up this letter, and with it my heart.

And yet I hope you will not tear it. I love you

And since I saw our family variance

And your too noble fearfulness withhold me

From my heart’s lord I have thrown from me shame

And the admirèd dalliance of women

To bridge it. Come to me, Antonio! Come,

But come in honour. I am not nor can be

So far degenerate from my house’s greatness

Or my pure self to love ignobly. Dear,

I have thrown from me modesty’s coy pretences

But the reality I’ll grapple to me

Close as your image. I am loth to end,

Yet must, and therefore will I end with this

‘Beloved, love me, respect me or forget me’.”

Writing more sweet than any yet that came

From heaven to earth, O thou dear revelation.

Make my lips holy. Ah, could I imagine

Thee the white hand that wrote thee, I were blest

Utterly. Thou hast made me twice myself.

I think I am another than Antonio.

The sky seems nearer to me or the earth

Environed with a sacred light. O come!

I’ll study to imprint this on my heart,

That when death comes he’ll find it there and leave it,

A monument and an immortal writing.

Damsel, you are of the Lady Ismenia’s household?

A poor relative of hers, Señor.

Your face seems strangely familiar to me. Have I not seen you in some place where I constantly resort?

O Sir, I hope you do not think so meanly of me. I am a poor girl but an honest.

How, how?

I know not how. I spoke only as the spirit moved me.

You have a marvellously nimble tongue. Two words with you.

Willingly, Señor, if you exceed not measure.

Fair one —

Oh, Sir, I am glad I listened. I like your two words extremely. God be with you.

Why, I have not begun yet.

The more shame to your arithmetic.

If your teacher had reckoned

as loosely with his cane-cuts, he would have made the carefuller scholar.

as loosely with his cane-cuts, he would have made the carefuller scholar.

God’s wounds, will you listen to me?

Well, Sir, I will not insist upon numbers. But pray, for your own sake, swear no more. No eloquence will long stand such draft105 upon it.

If you would listen, I would tell you a piece of news that might please you.

Let it be good news, new news and repeatable news and I will thank you for it.

Sure, maiden, you are wondrous beautiful.

Señor, Queen Anne is dead. Tell me the next.

The next is, I will kiss you.

Oh, Sir, that’s a prophecy. Well, death and kissing come to all of us, and by what disease the one or by whom the other, wise men care not to forecast. It profits little to study calamities beforehand. When it comes, I pray God I may learn to take it with resignation, if I cannot do better.

By my life, I will kiss you and without farther respite.

On what ground?

Have I not told you, you are beautiful.

So has my mirror, not once but a hundred times, and never yet offered to kiss me. When it does, I’ll allow your logic. No, we are already near enough to each other. Pray, keep your distance.

I will establish my argument with my lips.

I will defend mine with my hand. I promise you ’twill prove the abler dialectician of the two.

Well.

I am glad you think so, Señor. My lord, I cannot stay. What shall I tell my lady?

Tell her my heart is at her feet, and I

Am hers, hers only until heaven ceases

And after. Tell her that I am more blest

In her sweet condescension to my humbleness

Than Ilian Anchises when Love’s mother

Stooped from her golden heavens into his lap.

Tell her that as a goddess I revere her

And as a saint adore; that she and life

Are one to me, for I’ve no heart but her,

No atmosphere beyond her pleasure, light

But what her eyes allow me. Tell, O tell her —

Hold, hold, Señor. You may tell her all this yourself. I would not remember the half of it and could not understand the other half. Shall I tell her, you will come surely?

As sure as is the sun to its fixed hour

Or midnight to its duty. I will come.

Good! there are at last three words a poor girl can understand. Mark then, you will wait a while after nightfall, less than half a bowshot from the place you know towards the Square Velasquez, within sight of the Donna’s windows. Then106 I will come to you. Sir, if your sword be half as ready and irresistible as your tongue, I would gladly have you there with him, though Saint Iago grant that neither prove necessary. You look sad, Sir. God save you for a witty and eloquent gentleman.

O cousin, I am bewitched with happiness.

Pardon me that I leave you. Solitude

Demands a god and godlike I am grown

Unto myself. This letter deifies me.

I will be sole with my felicity.

God grant that I am not bewitched also!

Saints and angels!

How is it?

How did it happen?

Is the sun still in heaven?

Is that the song of a bird or a barrel-organ?

I am not drunk either.

I can still distinguish between a tree and the squirrel upon it.

What, am I not Basil? whom men call the witty and eloquent Basil?

Did I not laugh from the womb?

Was not my first cry a jest upon the world I came into?

Did I not invent a conceit upon my mother’s milk ere I had sucked of it?

Death!

And have I

been bashed and beaten by the tongue of a girl? silenced by a common purveyor of impertinences?

It is so and yet it cannot be.

I begin to believe in the dogmas of the materialist.

The gastric juice rises in my estimation.

Genius is after all only a form of indigestion, a line of Shakespeare the apotheosis of a leg of mutton and the speculations of Plato an escape of diseased tissue arrested in the permanency of ink.

What did I break my fast with this morning?

Kippered herring?

Bread?

Marmalade?

Tea?

O kippered herring, art thou the material form of stupidity and is marmalade an enemy of wit?

It must be so.

O mighty gastric juice!

Mother and Saviour!

I bow down before thee.

Be propitious, fair goddess, to thy adorer.

been bashed and beaten by the tongue of a girl? silenced by a common purveyor of impertinences?

It is so and yet it cannot be.

I begin to believe in the dogmas of the materialist.

The gastric juice rises in my estimation.

Genius is after all only a form of indigestion, a line of Shakespeare the apotheosis of a leg of mutton and the speculations of Plato an escape of diseased tissue arrested in the permanency of ink.

What did I break my fast with this morning?

Kippered herring?

Bread?

Marmalade?

Tea?

O kippered herring, art thou the material form of stupidity and is marmalade an enemy of wit?

It must be so.

O mighty gastric juice!

Mother and Saviour!

I bow down before thee.

Be propitious, fair goddess, to thy adorer.

Arise, Basil. Today thou shalt retrieve thy tarnished laurels or be expunged for ever from the book of the witty. Arm thyself in full panoply of allusion and irony, gird on raillery like a sword and repartee like a buckler. I will meet this girl tonight. I will tund her with conceits, torture her with ironies, tickle her with jests, prick her all over with epigrams. My wit shall smother her, tear her, burst her sides, press her to death, hang her, draw her, quarter her, and if all this fails, Death! as a last revenge, I’ll marry107 her. Saints!

Ismenia’s chamber.

Brigida lingers. O he has denied me

And therefore she is loth to come, for she

Knows she will bring me death. It is not so.

He has detained her to return an answer.

Yet I asked none. I am full of fear, O heart,

I have staked thee upon a desperate cast,

Which if I win not, I am miserable.

’Tis she. O that my hope could give her wings

Or lift her through the window bodily

To shorten this age of waiting. I could not

Discern her look. Her steps sound hopefully.

Dearest Brigida! at last! What says Antonio? Tell me quickly. Heavens! you look melancholy.

Santa Catarina! How weary I am! My ears too! I think they have listened to more nonsense in these twenty minutes than in all their natural eighteen years before. Sure, child, thou hast committed some unpardonable sin to have such a moonstruck lover as this Antonio.

But, Brigida!

And his shadow too, his Cerberus of wit who guards this poetical treasure. He would have eaten me, I think, if I had not given him the wherewithal to stop the three mouths of him.

Why, Brigida, Brigida.

Saints! to think how men lie! I have heard this Basil reputed loudly for the Caesar of wits, the tongue and laughter of the time; but never credit me, child, if I did not silence him with a few stale pertnesses a market-girl might have devised for her customers. A wit, truly! and not a word in his mouth bullet-head Pedro could not better.

Distraction! What is this to Antonio? Sure, your wits are bewildered, Brigida. What said Antonio? Girl, I am on thorns.

I am coming to that as fast as possible. Jesus! What a burning hurry you are in, Ismenia! You have not your colour, child. I will bring you salvolatile from my chamber. ’Tis in a marvellous cut-bottle with a different hue to each facet! I filched it from Donna Clara’s room when she was at matins yesterday.

Tell me, you magpie, tell me.

What am I doing else? You must know I found Antonio was in his garden. Oh, did I tell you, Ismenia? Donna Clara chooses the seeds for me this season and I think she has as rare a notion of nasturtiums as any woman living. I was speaking to Pedro in the summer house yesterday; for you remember it thundered terrifically before one had time to know light from darkness; and there I stood miles from the garden door —

In the name of pity, Brigida —

Saints! how you hurry me.

Well, when I went to Antonio in his garden — There’s an excellent garden, Ismenia.

I wonder

where Don Beltran’s gardener had his bignolias108.

where Don Beltran’s gardener had his bignolias108.

Oh-h-h!

Well, where was I? Oh, giving the letter to Antonio. Why, would you believe it, in thrust Don Wit, Don Cerberus, Don Subtle-three-mouths.

Will you tell me, you ogress, you paragon of Tyrannesses, you she-Nero, you compound of impossible cruelties?

Saints, what have I done to be abused so? I was coming to it faster than a mail-coach and four. You would not be so unconscionable as to ask me for the appendage of a story, all tail and nothing to hang it on? Well, Antonio took the letter.

Yes, yes and what answer gave he?

He looked all over the envelope to see whence it came, dissertated learnedly on this knotty question, abused me your handwriting

foully.

Dear cousin, sweet cousin, excellent Brigida! On my knees, I entreat you, do not tease me longer. Though I know you would not do it, if all were not well, yet consider what a weak tremulous thing is the heart of woman when she loves and have pity on me. On my knees, sweetest.

Why, Ismenia, I never knew you so humble in my life,— save

indeed to your brother; but him indeed I do not reckon.

He would rule even me, if I let him.

On your knees, too!

This is excellent.

May I be lost, if I am not tempted to try how long I can keep you so.

But I will be merciful.

Well, he scanned your handwriting and reviled it for the script of a virago, an Amazon.

indeed to your brother; but him indeed I do not reckon.

He would rule even me, if I let him.

On your knees, too!

This is excellent.

May I be lost, if I am not tempted to try how long I can keep you so.

But I will be merciful.

Well, he scanned your handwriting and reviled it for the script of a virago, an Amazon.

Brigida, if you will not tell me directly, without phrase and plainly, just what I want to know and nothing else, by heaven, I will beat you.

Now, this is foul. Can you not keep your better mood for fifty seconds by the clock? O temper, temper. Ah, well, where was I? Oh, yes, your handwriting. Oh! Oh! Oh! What mean you, cousin? Lord deliver me. Cousin! Cousin! He will come! He will come! He will come!

Does he love me?

Madly! distractedly! like a moonstruck natural! Saints!

Dearest, dearest Brigida! You are an angel. How can I thank you?

Child, you have thanked me out of breath already. If you have not dislocated my shoulder and torn half of my109 hair out —

Hear her, the Pagan! A gentle physical agitation and some rearrangement of tresses, ’twas less punishment than you deserved. But there! that is salve for you. And now be sober, sweet. What said Antonio? Come, tell me. I am greedy to know.

I’ll be hanged if I do. Besides I could not if I would. He talked poetry.

But did he not despise me for my forwardness?

Tut, you are childish. But to speak the bare fact, Ismenia, I think he is most poetically in love with you. He made preparations to swoon when he saw no more than110 your name; but I build nothing on that;111 there are some faint when they smell a pinch of garlic or spy a cockchafer. But he waited112 ten minutes copying your letter into his heart or some such note-book of love affairs; yet that was nothing either; I doubt if he found room for you, unless on the margin. Then he began drawing cheques on Olympus for comparisons, left that presently as antique and out of date, confounded Ovid and his breviary in the same quest; left that too for mediaeval, and diverged into Light and Heat, but came not to the very modernness of electricity. But Lord! cousin, what a career he ran! He had imagined himself blind and breathless when I stopped him. I tremble to think what calamities might have ensued had I not thrown myself under the wheels of his metaphor. The upshot is, he loves you, worships you and will come to you.

Brigida113, Brigida, be you as happy as you have made me.

Truly, the happiness of lovers, children, with a new plaything and mad to handle it.

But when they are tired of the game — ah, well, I will have nothing of it114.

No, I will115 be the type and patroness of spinsters,116 the noble army of old maids shall gather about my

tomb to do homage to me.

tomb to do homage to me.

And he will come tonight?

Yes, if his love lasts so long.

For a thousand years. Come with me, Brigida, and help me to bear my happiness. Till tonight!

This is the place.

’Tis farther.

This, I know it.

Here’s the square Velasquez. There in his saddle

Imperial Charles watches the silent city

His progeny could not keep. Where the one light

Stands beckoning to us, is Don Mario’s dwelling.

O thou celestial lustre, wast thou kindled

To be her light who is my sun? If so,

Thou art most happy. For thou dost inherit

The sanctuary of her dear sleep and art

The confidant of those sweet secrecies.

Though thou live for a night, yet is thy short

And noble ministry, more rich and costly,

Than ages of the sun. For thou hast seen,

O blessed, her unveiled and gleaming shoulder

Make her thick-treasured hair more precious. Thou

Hast watched that face upon her heavenly pillow

Slumbering amid its peaceful curls. O more!

For thou perhaps hast laid one brilliant finger

On her white breast mastered with sacred sleep,

And there known Paradise. Therefore thou’rt famous

Above all lights that human hands have kindled.

Here’s a whole epic on an ounce of oil

A poor, drowned wick bought from the nearest chandler

And a fly sodden in it.

Listen! one comes.

Stand back, abide not question.

They’ll not doubt us.

Am I mad?

Do you think I’ll trust a lover? Why, you could not

Even ask the time but you would say, “Good Sir,

How many minutes to Ismenia?”

Well,

Stand back.

No need. I see it. ’Tis the she-guide,

The feminine Mercury, the tongue, the woman.

You, my lord Antonio?

You are my guide to heaven.

O you have come?

I take this kindly of you, Señor. Tell me,

Were you not hiding when I came up to you?

Were you not hiding when I came up to you?

What was it, Sir? A constable or perhaps

A creditor? For to be dashed by a weak girl

I know you are too bold. What did you say?

I did not hear you. We are there, my lord.

Now quietly, if you love her, your sweet lady.

Can you be silent, Señor? We are lost else.

Ismenia’s antechamber.

Ismenia waiting118

It is too dark. I can see nothing. Hark!

Surely it was the door that fastened then.

My heart, control thyself! Thou beat’st119 too quickly

And wilt break in the arms of happiness.

Here. Enter, my lord, and take her.

Ismenia!

Antonio! Oh120 Antonio!

My heart’s dearest!

Bring your wit this way, Sir.

This is my place, dear, at your feet; and then

Higher than is my right.

I cannot suffer

Blasphemy to touch my heaven, though your lips

Have hallowed it.

Highest were low for you.

Highest were low for you.

You are a goddess and adorable.

Alas, Antonio, this is not the way.

I fear you do not love me, you despise me.

The leaf might then

Despise the moonbeam that has come to kiss it.

Then you must take me,

As I have given myself to you, your servant,

Yours wholly, not to be prayed to and hymned

As a divinity but to be commanded

As a dear handmaid. You must rule me, sweet,

Or I shall spoil with liberty and lose you.

Must I? I will then. Yet you are so queenly,

I needs must smile when I attempt it. Come,

Shall I command you?

Do, sweet.

Lay your head

Upon my shoulder so and do not dare

To lift it till I give you leave.

Alas,

I fear you’ll be a tyrant. And I meant

To bear at most a limited monarchy.

To bear at most a limited monarchy.

No murmuring. Answer my questions.

Well,

That’s easy and I will.

And truly.

Oh,

But that’s almost impossible. I’ll try.

Come, when did you first love me?

Dear, today.

When will you marry me?

Tomorrow, dear.

Here is a mutinous kingdom to my hands.

Truly then, seven days ago,

No more than seven, at the court I saw you,

And with the sight my life was troubled; heard you

And your voice tore my heart out. O Antonio,

I was an empty thing until today.

I was an empty thing until today.

I saw you daily, but because I feared

What now I know, you were Lord Beltran’s son

I dared not ask your name, nay shut my ears

To knowledge. O my love, I am afraid

Your father seems a hard vindictive man.

What will you do with me, Antonio?

Fasten

My jewel safe from separating hands

Holily on my bosom. My father? He

Shall know not of our love, till we are sure

From rude disunion. Though he will be angry

I am his eldest and beloved son,

And when he feels your sweetness and your charm

He will repent and thank me for a daughter.

When ’tis your voice that tells me, I believe

Impossibilities. Well, let me know —

You’ve made me blush, Antonio, and I wish

I could retaliate — were you not amazed

At my mad forwardness, to woo you first,

A youth unknown?

Yes, even as Adam was

When he first saw the sunrise over Eden.

It was unsunlike to uplift the glory

Of those life-giving rays, unwooed, uncourted.

Alas, you flatter. Did you love me, Antonio?

Three days before I had the bliss to win

The wonder of your eyes.

The wonder of your eyes.

Three days, Antonio? Three whole days before

I loved you?

Three days, dearest.

Oh,

You’ve made me jealous. I am angry. Three

Whole days! How could it happen?

I will make

You compensation, dear; for in revenge

I’ll love you three whole days, when you have ceased

To love me.

O not even in jest, Antonio,

Speak of such separation. Sooner shall

The sun divorce his light than we two sunder.

But you have given me a spur. I must

Love you too much, I must, Antonio, more

Than you love me, or the account’s not even.

One passes in the street.

We are

Too near the window and too heedless, love.

Come this way; here ’tis safe; I fear your danger.

Exeunt.

After a while enter Brigida.

After a while enter Brigida.

No sound? Señor! Ismenia! Surely they cannot have embraced each other into invisibility. No, Cupid has flown away with them. It cannot have been the devil, for I smell no brimstone. Well, if they are so tedious I will not mortify myself with solitude either. I have set Don Cerberus on the stairs out of respect for the mythology. There he stands with his sword at point like the picture of a sentinel and protects us against a surprise of rats from the cellar; for what other wild beasts there may be to menace us, I know not. Don Mario snores hard and Donna Clara plays the violin to his bassoon. I have heard them three rooms off. These men! these men! and yet they call themselves our masters. I would I could find a man fit to measure tongues with me. I begin to feel lonely in the Alpine elevation of my own wit. The meditations of Matterhorn come home to me and I feel a sister to Monte Rosa. Certainly this woman’s fever is catching, and spreads a121 most calamitous infection. I have overheard myself sighing; it is a symptom incubatory. Heighho! when turtles pair, I never heard that the magpie lives lonely. I have at this moment a kindly thought for all suffering animals. I begin to pity Cerberus even. I will relieve him from guard. Hist! Señor! Don Basil!

Not a mouse stirring!

Put up your sword, pray you; I think there is no danger, and if one comes, you may draw again in time to cut its tail off.

At your service, Señorita.

If it were not treason to my wit, I begin to feel this strip of a girl is making an ass of me.

I am transformed;

I feel it.

I shall hear myself bray presently.

But I will defy enchantment, I will handle her.

A plague!

Must I continually be stale-mated by a will-o’-the-wisp, all sparkle and nowhere?

Courage, Basil.

I feel it.

I shall hear myself bray presently.

But I will defy enchantment, I will handle her.

A plague!

Must I continually be stale-mated by a will-o’-the-wisp, all sparkle and nowhere?

Courage, Basil.

You meditate, Señor? If it be to allay the warmth you have brought from the stairs, with the coolness of reflection, I would not hinder you.

In bare truth, Señorita, I am so chilled that I was even about to beg of you a most sweet and warming cordial.

For a small matter like that, I would be loth to deny you. You shall have it immediately.

With your permission, then.

Ah, Señor, beware. Living coals are dangerous; they burn, Señor.

I am proof.

As the man said when he was bitten by the dog they thought mad; but it was122 the dog that died. Pray, Sir, have a care. You will put the fire out.

Come, I have you. I will take ten kisses for the one you refused me this forenoon.

That is too compound an interest. I do entreat you, Sir, have a care. This usury is punishable by the law.

I have the rich man’s trick for that. With the very coin I have unlawfully gathered, I will stop her mouth.

O Sir, you are as wasteful an accountant of kisses as of words. I foresee you will go bankrupt. No more, Señor, what noise was that on the stair? Good, now you have your distance. I will even123 trouble you to keep it. No nearer, I tell you. You do not observe the laws of the duello. You take advantages.

With me? Pooh, you grow ambitious. Because I knew that to stop your mouth was to stop your life, therefore in pity I have refused your encounter.124

Was it, truly? Alas, I could weep to think of the violence you have done yourself for my sake. Pray, sir, do not torture yourself so. To see how goodness is misunderstood in this world! Out of pity? And made me take you for a fool!

Well.

O no, Señor, it is not well, indeed it is not well.

You shall not do this again.

If I must die, I must die.

You are scatheless.

Pray now, disburden your intellect of all the brilliant things it has so painfully kept to itself.

Plethora is unwholesome and I would not have you perish of an apoplexy of wit.

Pour it out on me, conceit, epigram,

irony, satire, vituperation; flout and invective, tuquoque125

and double-entendre, pun and quibble, rhyme and unreason, catcall and onomatopoeia; all, all, though it be an avalanche.

It will be terrible, but I will stand the charge of it.

and double-entendre, pun and quibble, rhyme and unreason, catcall and onomatopoeia; all, all, though it be an avalanche.

It will be terrible, but I will stand the charge of it.

St. Iago! I think she has the whole dictionary in her stomach. I grow desperate.

Pray, do not be afraid. I do not indeed press you to throw yourself at my head, but for a small matter like your wit, I will bear up against it.

This girl has a devil.

Why are you silent, Señor? Are you angry with me? I have given you no cause. This is cruel. Don Basil, I have heard you cited everywhere for absolutely the most free and witty speaker of the age. They told me that if none other offer, you will jest with the statues in the Plaza Mayor and so wittily they cannot answer a word to you. What have I done that with me alone you are dumb?

I am bewitched certainly.

Señor, is it still pity? But why on me alone? O Sir, have pity on the whole world and be always silent. Well I see your benevolence is unconquerable. With your leave, we will pass from unprofitable talk; I would be glad to recall the sound of your voice. You may come nearer, since you decline the duello.

I thank you, Señorita. Whose sheep baaed then?

Don Basil, shall we talk soberly?

At your pleasure, Madam.

No Madam, Señor, but a poor companion. You go to Count Beltran’s house tomorrow?

It is so intended.

O the masque, who play it?

Masquers, Señorita.

O Sir, is this your pity? I told you, you would burst if you kept in your wit too long. But who are they by condition? Goddesses are the characters and by rule modern they should be live goddesses who play them.

They are so.

Are they indeed so lovely?

Euphrosyne, Christofir’s daughter, is simply the most exquisite beauty of the kingdom.

You speak very absolutely, Señor. Fairer than Ismenia?

I speak it with unwillingness, but honestly the Lady Ismenia, rarely lovely as she is, could not stand beside this miller’s126 daughter.

I think I have seen her and I do not remember so outshining a beauty.

Then cannot you have seen her, for the wonders she eclipses, themselves speak to their disgrace, even when they are women.

Pardon me if I take you to speak in the pitch of a lover’s eulogy.

Were it so, her beauty and gentleness deserve it; I have seen none worthier.

I wish you joy of her. I pray you for permission to leave you, Señor.

Save one indeed.

Ah! and who was she?

You will pardon me.

I will not press you, Sir, I do not know her, do I?

O ’tis not so much as that either.

’Twas only an orange-girl I

saw once at Cadiz.

saw once at Cadiz.

Oh!

Ha! she is galled, positively. This is as sweet to me as honey.

Well, Señor, your taste is as undeniable as your wit. Flour is the staff of life and oranges are good for a season. What does this paragon play?

Venus; and in the after-scene, Helen.

So? May I know the others? You may find one of them to be a poor cousin of mine.

Catriona, the bailly’s daughter to Count Conrad, and Sofronia, the student Geronimo’s127 sister; she too is of the Count’s household.

It is not then difficult to act in a masque.

A masque demands little, Señorita. A taking figure, a flowing step, a good voice, a quick memory — but for that a speaking memory hard by in a box will do much at an emergency.

True, for such long parts must be a heavy tax on the quickest.

There are but two such, Venus-Helen and Paris.

The rest are

only a Zephyr’s dance in, a speech and a song to help the situation and out again with a scurry.

only a Zephyr’s dance in, a speech and a song to help the situation and out again with a scurry.

God be with you. You have a learned conversation and a sober, and for such I will always report you. But here comes a colon to it. We will keep the full stop for tomorrow.

I think the dawn moves in the east, Brigida.

Pray you, unlock the door, but noiselessly.

Teach me not. Though the wild torrent of this gentleman’s conversation have swept away half my wit, I have at a desperate peril saved the other half for your service. Come, Sir, I have need of you to frighten the mice away.

Dear, we must part. I would have you my necklace

That I might feel you round my neck for ever,

Or life be night and all men sleep that128 we

Need never part: but we must part, Antonio.

When I cease to feel.

I know you cannot, but I am so happy.

I love to play with my own happiness

And ask it questions. Dear, we shall meet soon.

I’ll make a compact with you, sweet.

You shall

You shall

Do all my will and make no question, till

We’re married; then you know, I am your servant.

Till then and after.

Go now,

Love, I must drive you out or you’ll not go.

One kiss.

You’ve had one thousand. Well, one more,

One only or I shall never let you part.

Are you both distracted? Is this, I pray you, a time for lingering and near dawn over the east? Out with you, Señor, or I will set your own Cerberus upon you, and I wager he bites well, though I think poorly of his bark.

O I have given all myself and kept

Nothing to live with when he’s gone from me.

My life’s his moon and I’m all dark and sad

Without him. Yesterday I was Ismenia,

Strong in myself, an individual woman.

Today I’m but the body of another,

No longer separate reality.

Well, if I gain him, let me lose myself,

And I’m still happy. The door shuts. He’s129 gone.

Come, get in, get in. Snatch a little sleep, for I promise you, you shall have none tomorrow.

How do you mean by that? Or is it jest merely?

Leave me alone. I have a whole drama in my head, a play in a play and yet no play. I have only to rearrange the parts a little and tomorrow’s sunlight shall see it staged, scened, enacted and concluded. To bed with you.

A room in Conrad’s house.

Where is Flaminia130?

He’s in waiting, Sir.

Call him.

I never loved before. Fortune,

I ask one day of thee and one great night,

Then do thy will. I shall have reached my summit.

My lord!

(Incomplete)

A sketch by Sri Aurobindo of the plot of three

scenes of Acts II and III (From 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4)

Act II

Scene 1

Conrad and Flaminio arrange to surprise the Alcalde’s house and carry off Euphrosyne; Brigida converses with Conrad.

Scene 2

Jacinto monologuises; Jacinto and his father; Jacinto and Euphrosyne; students, friends of Jacinto. Conrad and Euphrosyne.

Act III

Scene 1

Beltran and his sons. Ismenia, Brigida.

Later edition of this work: The Complete Works of Sri Aurobindo: Set in 37 volumes.- Volumes 3-4.- Collected Plays and Stories.- Pondicherry: Sri Aurobindo Ashram, 1998.- 1008 p.

1 In 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4, there are 12 lines before this one:

Conrad

Till when do we wait here?

Roncedas

The Court is dull.

This melancholy gains upon the King.

Conrad

I should be riding homeward. How long it is

To lose the noble hours so emptily.

Roncedas

This is a daily weariness. But look:

The King has left his toying with the tassels

Of the great chair and turns slow eyes to us.

2 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: Your Highness?

3 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: What is your masque’s

4 In 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4, there are 3 lines after this one:

For which I still must thank your loyal pains

To cheer our stay in this so famous city?

Shall we hear it?

5 In 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4, instead of this line and next line there is one line:

Nothing from me, Your Highness.

6 In 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4 instead of this line and next five lines there are 12 lines:

And hearts that beat to tread of empires, cannot

Keep pace with dances, entertainments, masques.

But here’s my son, a piece of modern colour,

For now our forward children overstep

Their rough begetters — ask him, Sire; I doubt not

His answers shall reveal the grace men lend him

In attribution,— would ’twere used more nobly.

King Philip

Your son, Lord Beltran? Surely you fatigued

The holy saints in heaven and perfect martyrs

In your yet hopeful youth, till they consented

To your best wish. What masque, Antonio?

7 In 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4, there is a line after this one:

One little worthy, yet in a spirit framed

8 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: That may excuse much error; ’tis the Judgment

9 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: Guzman

10 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: Is that not very old?

11 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: Brigida

12 In 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4, there are 13 lines after this one:

King Philip

It has I think

Been staged a little often and though, Antonio,

I doubt not that fine pen and curious staging

Will raise it beyond new things rough conceived,

Yet is fresh subject something.

Antonio

For a play

It were so; this is none. Pardon me, Sir,

I err in boldness, urge too far my answer.

King Philip

Your boldness, youth, is others’ modesty.

Speak freely.

13 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: Thus I say then. A masque is heard

14 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: Once only and in that once must all be grasped at

15 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: But

16 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: While

17 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: over

18 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: If

19 In 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4 instead of this line there are two lines:

The mind is like a traveller pressed for time,

And quite engrossed with incident, omits

20 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: From haste to reach a goal.

21 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: old

22 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: Leaves it at leisure and it culls at ease

23 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: art

Throws in, to justify genius. These being lost

24 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: Then if old

25 In 1998 ed. this line is absent

26 amplifies

27 In 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4, instead of this line there are two lines:

For what’s creation but to make old things

Admirably new; the other’s mere invention,

28 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: A small gift

29 In 1998 ed. this line and next one are absent

30 In 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4, the all fragment is:

You are blessed, Lord Beltran, in your son. His voice

Performs the promise of his eyes; he is

A taking speaker.

31 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: You have, Lord Beltran, lands of which the fame

32 In 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4, the all line is: Gives much to Nature. I have not yet beheld them.

33 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: But

34 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: merely

35 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: great

36 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: So tell me,

37 In 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4, instead of this line and next line there is one line:

Have you not many lovely things to live with?

38 In 1998 ed. this line is absent

39 In 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4, there is a line before this one:

I have not time for hatred or revenge.

40 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: Sir

41 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: A patient

42 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: For

43 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: when

44 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: we

45 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: Not man

46 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: Nor angel, too

47 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: for

48 In 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4, instead of this line there are three lines:

Then vigorously his days endure till age

Sees his grandchildren climbing on his knees,

A happy calm old man; because he lived

49 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: expenditure

50 In 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4, instead of this line and next three lines (till words Inward a void...) there are these three lines:

Each mortal gift dependent on defect

And truth to one’s own self the only virtue.

The labourer physically is divine,

51 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: and

52 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: strengthening motion

53 In 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4, instead of this line there are two lines:

Abundant in her veins; her dumb attraction

Is as their mother’s arms, else like the lark

54 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: bound

55 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: towards the sun

56 In 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4, instead of this line and next line there are these two lines:

Full-tempered. Man Antaeuslike is strong

While he is natural and feels the soil

57 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: Let

58 In 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4, instead of this line and next line there are these three lines:

The city’s many-minded son preserve

And the clear-natured peasant unabridged

Their just, great uses, heighten or refresh

59 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: By

60 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: I’ld

61 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: noble, you,

62 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: close

63 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: Your

64 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: red-blooded

65 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: bloom

66 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: And there’s a Farmer’s

67 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: little

68 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: low knock

69 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: anger

70 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: If

71 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: Gladly I’ll clasp it, easily forget

72 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: You

73 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: do

74 much

75 In 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4, instead of this line and next three lines (till words Has no sharp edge) there are six lines:

Mine was the stronger. When I was but a boy

I carved your lands out. So had you won mine

If you had simply grappled fortune to you

And kept her faithful with your sword. ’Tis not

Crooked dexterity that has the secret

To win her. Briefly I hold your lands and satire

76 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: favourites

77 In 1998 ed. this part of this line and all next line are absent

78 In 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4, there ia a line after this one:

Exit Conrad.

79 In 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4, there ia a line after this one:

What task?

80 In 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4, the all line is:

Some girl-lifting. What other task

81 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: Will he have now?

82 sheep,

83 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: hidden frailness

84 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: You’ve

85 for

86 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: you’re

87 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: I’ld

88 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: breed

89 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: this and without

90 In 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4, instead of this line there are two lines:

Well, quickly teach

Your diagram. Suppose your maid and win her.

91 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: love for

92 In 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4, there is a line before this one:

I

93 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: Marlborough

94 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: pock

95 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: length — no

96 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: indefinable — no

97 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: no! that fits not in; a

98 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: not you

99 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: I think you

100 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: unforgotten

101 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: Here is

102 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: recognise

103 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: the

104 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: Lest

105 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: drafts

106 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: There

107 beat

108 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: bignonias

109 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: half my

110 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: no more than saw

111 but there was nothing in that;

112 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: wasted

113 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: O Brigida

114 In 1998 ed. these words are absent

115 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: I’ll

116 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: of all spinsters and

117 In 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4, there is a line after this one: Antonio, Basil.

118 In 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4, instead of this line there are two lines:

Ismenia waiting.

Ismenia

119 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: beatst

120 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: O

121 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: a

122 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: ’twas

123 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: ev’n

124 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: encounter, in pure pity.

125 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: tu quoque

126 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: farmer’s

127 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: Jeronimo’s

128 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: then

129 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4: He is

130 1998 ed. CWSA, volumes 3-4, sic passim: Flaminio