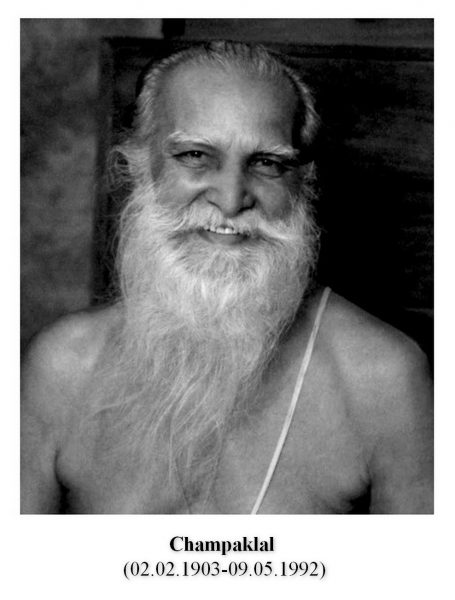

When I arrived at the Ashram in 1971, Champaklal was a rarely-seen, almost legendary figure. He had come to Pondicherry from Gujarat as a young man, worked closely with the Mother from the beginning, attended Sri Aurobindo personally for twenty-five years and then the Mother for nearly as long. I first saw him on December 12th when I went to meet the Mother in her room. Before turning to her I glanced at him and he welcomed me with a big smile. Then after the Mother’s passing in 1973, I often saw him on Saturday evenings at the Playground. Five minutes before the weekly film began, he would burst through the gate, barrel-chest boldly stuck out, and stride to his place on the sandy ground. I got to know him personally in 1987, when he called me to do some work for him.

One day late in May 1987, Roshan Dumasia, a Bombay University Professor who assisted Champaklal during her vacations, came to my desk at the Archives and said that Champaklal wished to see me. He needed someone to transcribe some manuscripts of Sri Aurobindo, mainly letters and messages. After taking permission from my department head, Jayantilal, I agreed to help. Over the next two years I spent an hour or more with Champaklal on about a dozen occasions. At first I called him ‘Champaklalji’, but soon it became ‘Dadaji’, as he was called by those close to him.

The 1987 Meetings

My first work was to type out Champaklal’s own correspondence with Sri Aurobindo. The full correspondence was being prepared by Roshan for a revised edition of the book Champaklal Speaks. On June 3rd I went to his room with a typed copy of the manuscripts he had given for transcription. Champaklal looked at my work slowly and carefully. Now and then he expressed his appreciation with a smile, a gleam in his eyes, a lively hand movement. Something of a mime artist, he had a mobile face and a gift for conveying his thoughts and emotions through gestures. I was happy that he took so much time to see my work. Later I found that he took time for almost everything he did.

During the final years of his life Champaklal observed a vow of silence (mauna vrat), so, any verbal communication between us had to be done through writing. After checking my work he wrote on a slip of paper, “I admire you”, and handed it to me. I read the words and blushed with embarrassment. Then he took the slip again and added, “You work with love and joy.” Flushed with elation I blurted out, “I admire you too!” and explained, “To me you stand for service, freedom and wideness of mind. You do what you think is right, regardless of what other people say.” I had in mind his recent travels in India and abroad, for which he was sometimes criticised in the Ashram; the prevailing view was that he should have stayed at home. In reply to what I told him, Champaklal wrote, “Because of Her abundant Grace.” As I came to learn, it was typical of him to attribute any merit in himself to the Mother.

Sharing a Laugh

On June 12th I went to his room with a second batch of manuscripts and my transcription of them. While Champaklal looked over my work, I peeked around the room. Pictures everywhere — on all four walls, from floor to ceiling, big black-and-white photographs and a few brightly-coloured paintings. Mother and Sri Aurobindo all around. A soft yellow-gold carpet covered the floor. Seated on it comfortably, clad only in a white loincloth, with his golden-brown skin showing everywhere, Champaklal looked like a happy child. After checking my transcript he wrote, “Mother used to like good work so much. Now even more — must be!” I laughed, pleased with the idea that Mother now appreciates our work more than ever. He also laughed and it was good to hear his chuckles. Then he wrote, “Champaklal respects and admires very much such a person.” Touched by his compliment I said, “Your kind words give me faith in myself.” In response he wrote, “The qwaliti (sic) is Hers.”

The Case of the Missing Photo

The next day Roshan brought a third batch of manuscripts to me for transcription. She also asked me to speak to Jayantilal on a delicate matter. Champaklal had given him, she said, a large hand-coloured photograph of the Mother, but it had not been returned and Champaklal wanted it back. Later in the day I asked Jayantilal about this photo. He said that Champaklal had given him a copy of the photo, not the large original, and Jayantilal had been careful to return the copy, knowing that Champaklal was particular about such things.

A few days later I went to see Champaklal for work and broached the subject of the missing photo. “Jayantilal says he doesn’t have the photo,” I said. “He told me that you gave him a smaller copy of it and he returned it.” Champaklal’s face suddenly darkened and he grimaced; he clearly did not buy this story! The air became heavy with tension as he struggled to contain the rising anger in him. Apparently he thought that Jayantilal still had the photo or had misplaced it and was making an excuse. There was a long, ominous silence. I could hardly breathe. At last the tension lessened, Champaklal’s face relaxed and he gave a weary smile. Picking up a slip of paper, he penned three words and handed the slip to me with a gesture of resignation. “Does not matter,” it said. Maybe not, I thought, but something is not right.

There was another long and heavy silence. Then Champaklal’s whole countenance softened and his face underwent a visible metamorphosis. A growing warmth and joy spread across it, the gravity in the air abated, and I could breathe freely again. He reached for a slip of paper and slowly wrote, “So many things Champaklal has lost — now one more.” Handing me the slip, he smiled with a look of compassion tinged with sorrow. This look of his was most touching. It seemed to me that he probably thought the missing photo might still be somewhere with Jayantilal, but he was not pressing for it. His unspoken message was: “So many things I have lost in my life. Who am I to get angry and point the finger of blame at someone else?” I felt great sympathy and respect for him. He had passed the test — he had faced the dark cloud of anger in himself and dissolved it. In place of the cloud a radiant glow of tenderness shone on his face; his heart was again at peace. How honest one must be to remain bright and happy.

After a week Champaklal sent a letter of apology to Jayantilal for any anxiety he might have caused. He had not yet found the missing photo, he wrote, but he thought that it must be somewhere with him or perhaps he had given it to someone else. The latter surmise turned out to be true: years later I found the original hand-coloured photograph in the room of my downstairs neighbour!

Only One Sadhana

Towards the end of June I returned the third batch of manuscripts to Champaklal. There was very little work that day, so I spoke to him about something that was bothering me. “Dadaji,” I said, “I do japa to control my mind, but I don’t have a mantra. I have tried so many mantras, but I can’t settle on one. Could you suggest a mantra for me?” He slowly inscribed on a chit: “What I think. Any mantra you say with love and joy is good. But it is not necessary. Only if it comes spontaneously.” As I read his reply, Champaklal watched my face and he could tell that I was not satisfied; in fact I was still hoping that he would give me a mantra. He smiled and wrote, “I myself do not have a mantra.” That did satisfy me — it meant we were both in the same boat! Again he took up his pen and wrote: “To me Mother gave only one sadhana.” Then he pulled out a birthday card that contained a message she had written to him in the early 1930s:

Be simple,

Be happy,

Remain quiet,

Do your work as well as you can.

Keep yourself open always towards me.

This is all that is asked from you.

Champaklal wrote, “I asked her: ‘You say, “This is all that is asked from you.” All? Only this?’ Mother said, ‘Only this.’ I said, ‘Mother, just give me one.’” — that is, just one of the five things she had listed. He ended his note, “By her Grace she has given them all to me. This is my condition. I want nothing.” At the end of our session he handed me a packet of incense and a Divine Love flower.

The 1988 Meetings

At the end of the summer of 1987 Roshan left the Ashram to resume her teaching duties in Bombay. When she came back in April 1988, we took up work with Champaklal again. I went to his room on the 28th with a framed photograph he had given me the year before, a little-known photo of the Mother taken on her birthday in 1973. She is wearing a dark red sari embroidered in gold and on her head is a large gold triangular crown with her symbol on it. Her eyes are closed and she is indrawn. When I first saw the photo, I was deeply attracted to it, so he gave it to me! But over the months I had not looked at it much. “I want to return this photo to you,” I said. “I have not been feeling much for it lately.”

Happy to see the photo again, he looked intently at it for about two minutes. As he gazed, his face took on an uncanny resemblance to the face of the Mother in the photo; the extent of his identification was remarkable. Then he began a forty-minute ‘discussion’ of the photograph, with him writing and me commenting every now and then.

“Why don’t people like this photo?” he wrote. I didn’t know what to say. Then he asked me to read out aloud something he had written about the photo, a two-page typescript. The gist of it was that although the photograph is not superficially pleasing, it expresses a deep inner state, and if one looks at it for a few minutes one will be drawn deep inside — this was his own experience. The photograph is merely a symbol of the Mother, just as the stone image of Kali worshipped by Ramakrishnadev at Dakshineshwar is a symbol of Mother Kali. By dwelling on the symbol one can enter into the consciousness behind it. At this point Champaklal showed me a coloured print of Jagannath of Puri, with Balaram and Subhadra on either side of him. “Chaitanyadev had darshan of Krishna by seeing this image,” he wrote. Then he asked me a whole series of questions about the Mother’s photo, sometimes supplying the answers himself.

“Why don’t people like it?” he wrote.

“Because Mother is not smiling and she looks so serious,” I said.

“But she is not smiling in other photos,” he countered.

“Her eyes are closed,” I said, “so people don’t know what she is thinking. It makes them afraid.”

Champaklal’s eyes lit up with a gleam. “FEAR,” he wrote. “They are afraid to go within.”

Still absorbed in the subject, he penned, “Is the gold crown not beautiful? Mother liked it very much.” Pointing to the photo, he wrote, “Mother liked it very much. She looked at it happily for a long time in my presence.” And then, “She signed a copy of it for someone and gave her blessings. She never signed if she did not like a photo.” About the copy I had returned, he wrote, “It wanted to come back to me.”

After this unusual session, Champaklal sent me off with a packet of incense and a Divine Love flower.

Preservation of Manuscripts

A week later, on May 5th, I went to see Champaklal at 10.30 in the morning. We had a long discussion on the preservation of manuscripts. I told him that it was not safe for him to keep his manuscripts of Sri Aurobindo and the Mother enclosed in plastic sheets, because the plastic would decompose in time and contaminate the manuscripts with acid, turning them yellow and shortening their lifespan. After questioning me closely, even about the effect of the acids contained in the manuscripts themselves, he agreed to remove the plastic sheets. Later I supplied him with thin, non-acidic paper folders for the work.

Dwelling in the Zone

Champaklal was conscientious in his care for material things, deliberate and thorough. Perhaps because he was solidly grounded, I always felt at ease and secure with him. It took a long time to do things, but I didn’t feel we were wasting time. I sensed that even while he did things, he dwelt inwardly in a contented spiritual zone. While his outer nature did the work, his inner being remained concentrated within: he was one-fourth outside and three-fourths inside. In his presence I basked in an atmosphere of serenity, removed from the pressing concerns of life. He had learned, I think, the truth of the Mother’s comment, “As soon as one stops hurrying, one enters a truer vibration.”

Little Jokes

My third visit took place on May 12th. We didn’t work much, but it was a joy just to sit there in his presence. Then, towards the end, I got restless and started making gestures to get up and go. Champaklal either ignored them or smiled without giving me a nod to leave, so I sat on. Then someone came who said he needed to see Champaklal for two minutes and asked to be left alone with him. I went into the next room and waited. Ten minutes later the fellow came out and left. I returned to Champaklal’s room. “Why did you leave?” he wrote. “X asked to be alone with you,” I said. He smiled mischievously and wiggled two fingers back and forth, as if to say, “Yes, but only for two minutes!” I thought this was very funny, so I laughed. He also laughed and his eyes sparkled. I think he was happy to have someone to enjoy his little jokes.

That day Champaklal started to get up to bring a flower for me from Sri Aurobindo’s room, but feeling weak he sank back down again. I motioned for him to stay put — no need to send me off with a flower each time. So he just sat there like a child with a big smile on his face, and I left.

Willing Work, No Obligation

Five days later, on May 17th, I went to see him again. There was not much to do, but the time passed easily. We sank into an enjoyable meditative state. After a while Champaklal wrote that he would like to have new photocopies made of his Bonne Fête notebook in which Sri Aurobindo and the Mother had for many years written birthday messages for him. He showed me the old photocopies, which were small and faded, with shadowy lines at the edges. “Very bad job,” he wrote. I asked, “Do you want the new copies to be the same size as the originals?” “If you can,” he wrote. “Of course we can,” I said. “Yes, you can,” he rejoined, “but can he?” ‘He’ was the person who had not shown much enthusiasm for doing such work in the past. We both laughed. Then he wrote, “Do it if he is willing, but not if he feels obliged.” That was Champaklal’s style: he freely asked people to do things for him, but he wanted them done willingly. At the end of the hour he sent me off with incense and a flower.

The Art of Living

My final meeting with Champaklal that year took place the next day, May 18th. That evening he was leaving Pondicherry for a two-month tour of Europe and the United States. I expected him to be very busy, maybe packing, and was prepared to leave early to spare his time. When I arrived at 10.30 he was working as usual with Roshan. I sat on the floor and waited fifteen minutes until they finished their work together. By then I had calmed down. Suddenly old Dikshitbhai, well into his nineties, appeared at the door to wish Champaklal Bon voyage for his journey abroad. When Dikshitbhai showed deferential respect to his younger gurubhai, Champaklal put his head down like an embarrassed little boy and said nothing. Dikshitbhai sat down on the carpet and we spent several minutes sitting in silence; then he got up to go. Champaklal came out of his ingathered condition, held Dikshitbhai’s hand warmly and gave him some flowers.

I felt it was time for me to go too and started to get up. Champaklal smiled and motioned to me with his eyes to remain seated. Quickly he sank down again into an indrawn state. Roshan and I also became indrawn. Five minutes, ten minutes, I kept going deeper and deeper. Then I understood! He was leaving for Europe that evening and had things to do, but no, he was not all tensed up and in a hurry; he was doing the only thing really worth doing, plunging inside, living in the Presence. Indeed, he seemed to have forgotten the time! The minutes passed slowly, but I was so tranquillised that I lost the impulse to go. A great wave of affection arose in me and flowed towards this kindly man who was teaching me by his own example the art of living: Remember the important thing, the inner presence. Don’t be running around all the time. Learn to appreciate and enjoy the Grace.

At last, emerging from the little meditation he had induced in us, Champaklal got up, went into Sri Aurobindo’s room and returned with two kinds of incense and a Divine Love flower. Handing them to me, he smiled sweetly. I stepped out the door as he watched me go.

My Mother Meets Champaklal

That was my last long meeting with Champaklal. In the years that followed, I saw him a number of times, but only briefly. Still, he remembered me and made me feel special. Once, towards the end, I brought my mother to see him. He was weak as a kitten, having suffered a stroke, and leaned back on the pillows that propped him up. But the kind and gentle eyes were still there. My mother stood before him a while and then, on impulse, held out her hand to him. Champaklal held it a few seconds. When she began to withdraw her hand, he held on and resisted her pull; then he let her hand slowly go back towards her and, at the last moment, he tugged it towards himself. My mother broke down crying. Later she told me, “Oh, Rob, that man is very special.” Yes, Mom, he is indeed very special.

Bob Zwicker

Originally appeared in Mother India, May 2017