But this very attitude of wanting to become identified with the Unmanifest and letting the world suffer, isn’t this selfishness?

Yes. And so what happens is very remarkable, the result is always the same: those who have done that, at the last minute, have received a sort of intimation that they had to return to the world and do their work. It is as though they reached the door and — “Ah! no, no, not yet — go back and work. When the world is ready, then this will be all right.”

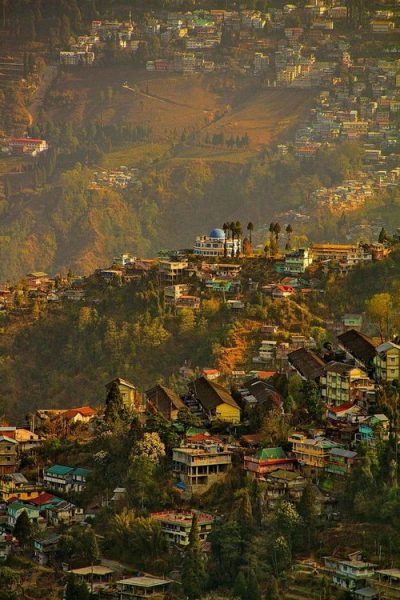

Indeed this attitude of flight in the face of difficulty is a supreme selfishness. You are told, “Do this, and then, when all the others have done it, all will be well with the whole world”, but it is only a very small elite among men who are ready to be able to do it. And these precisely are those who can be the most useful to the earth, for they know more about things than others, they have overcome many difficulties and can be of help to others just where those others can’t. But the whole human mass, the immense human mass…. For when some have succeeded — even a few hundred — one may tend to think it is “humanity”, but truly speaking it is only a kind of elite of humanity, it is a selection. The immense mass, all the people living all over the earth — merely in India, the immense population — formidable — which lives in the villages, the countryside, there is no question of their making an effort for liberation, to come out of the world in order to live the spiritual life. They don’t even have the time to become aware of themselves! They are just there, attached to their work like a horse to the plough. They move in a rut from which, generally, they can’t get out. So they can’t be told, “Do as I do and all will be well.” Because “Do as I do” means nothing at all. There are perhaps a few hundred who can do the same thing, no more!

24 February 1954

***

“… all work must be afield of endeavour and a school of experience.” (Sri Aurobindo) “All work” is “a school of experience” ?

Yes, surely. You don’t understand?

No, Mother.

If you don’t do anything, you cannot have any experience. The whole life is a field of experience. Each movement you make, each thought you have, each work you do, can be an experience, and must be an experience; and naturally work in particular is a field of experience where one must apply ail the progress which one endeavours to make inwardly.

If you remain in meditation or contemplation without working, well, you don’t know if you have progressed or not. You may live in an illusion, the illusion of your progress; while if you begin to work, all the circumstances of your work, the contact with others, the material occupation, all this is a field of experience in order that you may become aware not only of the progress made but of all the progress that remains to be made. If you live closed up in yourself, without acting, you may live in a completely subjective illusion; the moment you externalise your action and enter into contact with others, with circumstances and the objects of life, you become aware absolutely objectively of whether you have made progress or not, whether you are more calm, more conscious,  stronger, more unselfish, whether you no longer have any desire, any preference, any weakness, any unfaithfulness — you can become aware of all this by working. But if you remain enclosed in a meditation that’s altogether personal, you may enter into a total illusion and never come out of it, and believe that you have realised extraordinary things, while really you have only the impression, the illusion that you have done so.[…]

stronger, more unselfish, whether you no longer have any desire, any preference, any weakness, any unfaithfulness — you can become aware of all this by working. But if you remain enclosed in a meditation that’s altogether personal, you may enter into a total illusion and never come out of it, and believe that you have realised extraordinary things, while really you have only the impression, the illusion that you have done so.[…]

Then, Mother, why do all the spiritual schools in India have as their doctrine escape from action?

Yes, because all this is founded upon the teaching that life is an illusion. It began with the teaching of the Buddha who said that existence was the fruit of desire, and that there was only one way of coming out of misery and suffering and desire; it was to come out of existence. And then this continued with Shankara who added that not only is it the fruit of desire but it is a total illusion, and as long as you live in this illusion you cannot realise the Divine. For him there was not even the Divine, I think; for the Buddha, at least, there wasn’t any.

Then did they truly have experiences?

That depends on what you call “experience”. They certainly had an inner contact with something.

The Buddha certainly had an inner contact with something which, in comparison with the external life, was a non-existence; and in this non-existence, naturally, all the results of existence disappear. There is a state like this; it is even said that if one can keep this state for twenty days, one is sure to lose one’s body; if it is exclusive, I quite agree with it.

But it may be an experience which remains at the back, you see, and is conscious even while not being exclusive, and which causes the contact with the world and the outer consciousness to be supported by something that is free and independent. This indeed is a state in which one can truly make very great progress externally, because one can be detached from everything and act without attachment, without preference, with that inner freedom which is expressed outwardly.

Yet this is the real necessity: once this inner freedom has been attained and the conscious contact with what is eternal and infinite, then, without losing this consciousness one must return to action and let that influence the whole consciousness turned towards action.

This is what Sri Aurobindo calls bringing down the Force from above. In this way there is a chance of being able to change the world, because one has brought in a new Force, a new region, a new consciousness and put it into contact with the outer world. So its presence and action will produce inevitable changes and, let us hope, a total transformation in what this outer world is.

So we could say that the Buddha quite certainly had the first part of the experience, but that he never dreamt of the second, because it was contrary to his own theory. His theory was that one had to run away; but it is obvious that there is only one way of escape, to die, and yet, as he himself has said so well, you may be dead and be completely attached to life, and still be in the cycle of births and not have liberation. And in fact he has admitted the idea that it is by successive passing lives on the earth that one can manage to develop oneself to reach this liberation. But for him the ideal was that the world would not exist any longer. It was as though he accused the Divine of having made a mistake and that there was only one thing to do, to rectify the mistake by annulling it. But naturally, to be reason able and logical, he did not admit the Divine. It was a mistake made by whom, how, in what way? — this he never explained. He simply said that it was made and that the world had begun with desire and had to end with desire. He was just on the point of saying that this world was purely subjective, that is, a collective illusion, and that if the illusion ceased the world would cease to be. But he did not come so far. It is Shankara who took over and made the thing altogether complete in his teaching.

If we go back to the teaching of the Rishis, for example, there was no idea of flight out of the world, for them the realisation had to be terrestrial. They conceived a Golden Age very well, in which the realisation would be terrestrial. But starting from a certain decline of vitality in the spiritual life of the country, perhaps, from a different orientation which came in, you see… it is certainly starting from the teaching of the Buddha that this idea of flight came, which has undermined the vitality of the country [India], because one had to make an effort to cut oneself off from life. The outer reality became an illusory falsehood, and one had no longer to have anything to do with it. So naturally one was cut off from the universal energy, and the vitality went on diminishing, and with this vitality all the possibilities of realisation also diminished.

7 September 1955

About Savitri | B1C1-10 The Response of Earth (p.5)