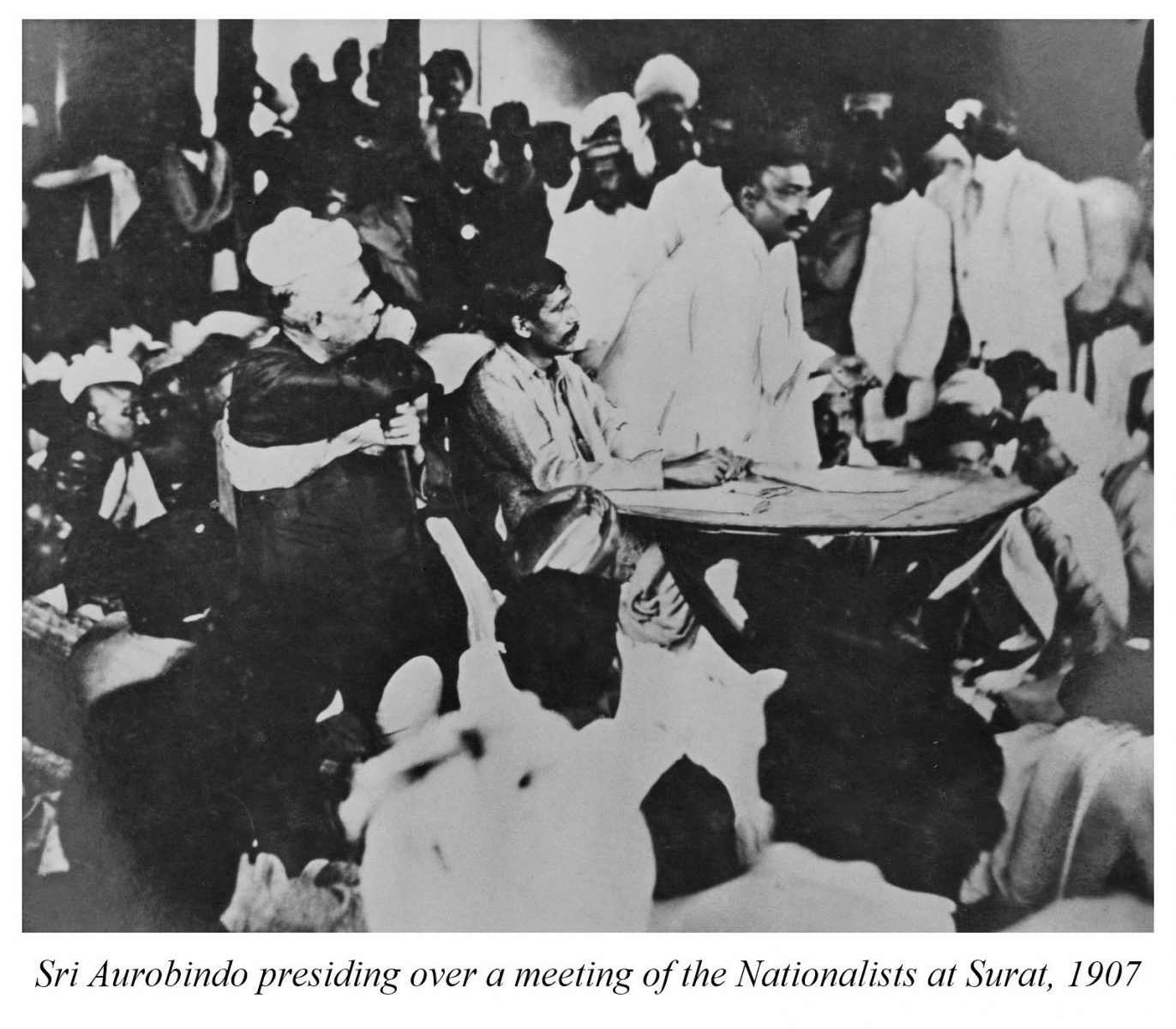

“Grave and silent — I think without saying a single word — Mr. Aravinda Ghose took the chair, and sat unmoved, with far-off eyes, as one who gazes at futurity. In clear, short sentences, without eloquence or passion, Mr. Tilak spoke till the stars shone out and some one kindled a lantern at his side…”

— Mr. Nevinson (The New Spirit in India)

The above remark from a perceptive foreigner gives a vivid description of Sri Aurobindo in his characteristic pose and poise at the nationalist Conference at Surat, “…sat unmoved, with far-off eyes, as one who gazes at futurity” — a description which whosoever saw Sri Aurobindo anywhere at close quarters would readily bear out. Surat Congress was broken, the Nationalists and the Moderates had drifted apart, and the dim hopes of a united. Congress were extinguished for many a long year to come. But the fracas and turmoil, and the momentous sequel to the disruption of the Congress failed to shake the Yogic poise, the Yogic equality, samattwa, of Sri Aurobindo. He did not live from moment to moment, and attached not himself to the passing events, but looked unmoved through them to the great future he was commissioned to shape. Beyond the dust and din of the present, and undeterred by them, he pursued the inner light to which he had surrendered himself. There is no fear or failure for the eye that sees, and no disappointment for the heart that knows and reposes in the Divine Will. Dwelling in the Eternal, the Yogi shares the Eternal’s delight in Its unfolding play in the flux of time.

Describing the Yogic samattwa in his book, The Synthesis of Yoga, Sri Aurobindo writes: “We shall have the… equality of mind and soul towards all happenings, painful or pleasurable, defeat and success, honour and disgrace, good repute and ill-repute, good fortune and evil fortune. For in all happenings we shall see the will of the Master of all works and results and a step in the evolving expression of the Divine.”

A mighty step had been taken, “…a new spirit, a different and difficult spirit, had arisen in the country,” says Nevinson. History was being made. The National Congress, after the Surat session, became the close preserve of the Moderates, who served the country as best they could, consistently with their avowed loyalty to the British crown and their implicit faith in British justice. But they did not represent the intense yearning for freedom and the burning love for the motherland, which had been generated since 1905. They could not — they did not much bother to — carry the people with them. Their ranks began to thin, and their annual sessions were attended only by a dwindling number of men. The Nationalists, on the other hand, were dispersed in several groups, indignant and disorganised, and most of them, at least those who were ardent and daring, took to secret revolutionary activities, and some to terrorism as the only means of winning freedom. The blind fury of vindictive repression made its desperate bid to stamp out the spirit of freedom, stone-blind to the historic fact that the spirit of freedom, once kindled, can never be stamped out. Lajpat Rai and Bepin Pal were away from India; Sri Aurobindo was soon clapped into Alipore jail as an under-trial prisoner, and Tilak was in deportation in Mandalay. Absence of the topmost leaders and an intensification of the repressive measures by the Government forced the nationalist fire to sink. But the fire did not die out; it smouldered on, and the secret revolutionary activities grew apace, sporadic but violent, till 1914, when Tilak returned from Mandalay and joined hands with Annie Beasant, and gave a fresh impetus and a new direction to the national urge for freedom.

Sri Aurobindo had been feeling at this time the need of a guidance and a new direction in his Yoga. Though, as we learn from his confidential letters to his wife, he was being led by the Divine within, he had arrived at a stage when a crucial experience alone could clear the way for further advance. It was almost like Sri Ramakrishna’s acceptance of the spiritual help of the Naga Yogi, Totapuri, or of the Tantric Yogini, Bhairavi. Sri Aurobindo expressed his wish to consult a Yogi to Barin, his younger

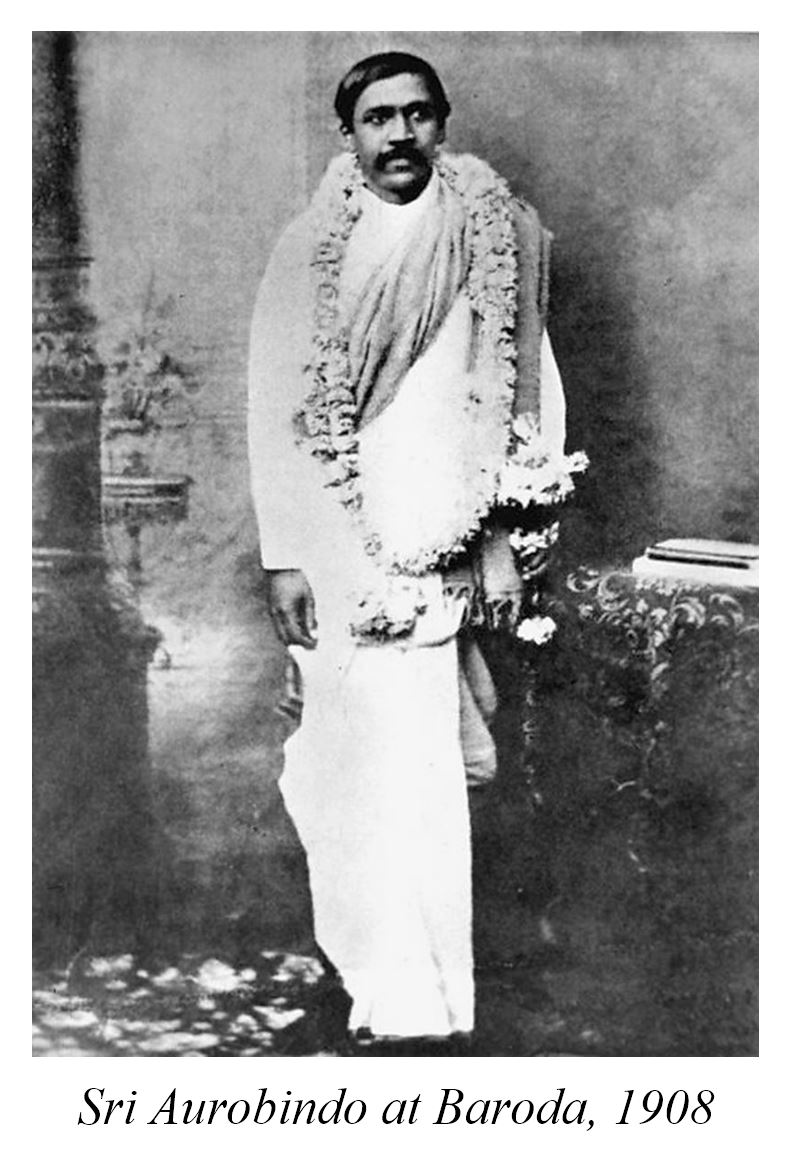

brother. Barin procured the address of Yogi Vishnu Bhaskar Lele[1] and wired to him at Gwalior to come to Baroda and see Sri Aurobindo. Sri Aurobindo came to Baroda from Surat. Barin says in his autobiography that the Principal of the Baroda College had asked the students not to meet Sri Aurobindo or go to listen to his lectures, as he was then a nationalist politician. But the students, who were devoted to Sri Aurobindo and had been so much inspired by his noble character and intense patriotism, could not obey the ban and ran out of their classes to meet him on his arrival. They unyoked the horses of his carriage and drew the carriage themselves. Sri Aurobindo delivered three lectures there on the political situation. Sardar Majumdar presented him with a Pashmina shawl as it was severe winter and he was only in cotton dhoti and shirt and had no wrapper to cover his body. He kept no bedding with him, and, while travelling by train, he slept on the bare, wooden bunk of a third class compartment and used his arm for a pillow.[2]

Sri Aurobindo met Lele on one of the closing days of December, 1907[3] at the residence of Khasirao Jadav, where he and Barin were put up. Lele advised him to give up politics, but as it was not possible, he asked him to suspend it for a few days and stay with him. Accordingly, they closeted themselves in a room in Sardar Majumdar’s house for three days. Let us now hear from Sri Aurobindo himself about his experiences during those three days: “‘Sit down’, I was told, ‘look and you will see that your thoughts come into you from outside. Before they enter, fling them back.’ I sat down and looked and saw to my astonishment that it was so; I saw and felt concretely the thought approaching as if to enter through or above the head and was able to push it back concretely before it came inside. In three days — really in one — my mind became full of an eternal silence — it is still there”.[4] About Lele he said once that he was “a Bhakta with a limited mind but with some experience and evocative power”.[5] Referring to the same experience, he says in Yoga II, Tome II: “From that moment, in principle, the mental being in me became a free intelligence, a universal Mind, not limited to the narrow circle of personal thought as a labourer in a thought factory, but a receiver of knowledge from all the hundred realms of being and free to choose what it willed in this vast sight-empire.” Again in Tome I, On Yoga II, he says: “…A calm and silence that is what I had. The proof is that out of an absolute silence of the mind I edited the Bande Mataram for 4 months and wrote 6 volumes of the Arya, not to speak of all the letters and messages etc., etc. I have written since.” Dwelling on the implications of the realisation, he says, “…we sat together and I followed with absolute fidelity what he instructed me to do, not myself in the least understanding where he was leading me or where I was myself going. The first result was a series of tremendously powerful experiences and radical changes of consciousness which he had never intended — for they were Adwaitic and Vedantic and he was against Adwaita Vedanta — and which were quite contrary to my own ideas[6], for they made me see with a stupendous intensity the world as a cinematographic play of vacant forms in the impersonal universality of the Absolute Brahman.[7]”

Evidently, it was an experience of what the Gita calls Brahma-Nirvana. The Akshara Brahman alone existed, all-pervasive, silent, passive and immutable, and the world appeared as “a cinematographic play of vacant forms in the impersonal universality of the Absolute Brahman.” It was this authentic, indubitable experience upon which the great Shankaracharya stood in his appraisement of the world, and in his interpretation of the scriptures. The world did appear to him as a cinematographic play, viśvaṁ darpaṇadṛśyamānanagarītulyam, а Мауа, real and yet unreal. He could not deny his own concrete spiritual experience of the impersonal universal immutability of the Brahman, and against it of the world as a procession of phantom forms, appearing and disappearing in the silent stillness of the sole reality of the Brahman. He could deny neither. He, therefore, conceded only a phenomenal, practical reality, vyāvahārika satya, to the world, but not eternal or pāramārthika (spiritual). Renunciation of the world and the speedy adoption of the ascetic life of the recluse for a total self-extinction in the Brahman were the inevitable corollary of this dual experience — māyāmayam idaṁ nikhilaṁ hitvā. But if he had gone beyond this experience of the immutable impersonality of the Akshara Brahman, he could have seen and realised the spiritual reality of the world too. He could have said in the unambiguous words of the Upanishads: ātmata eva idaṁ sarvam, from the self and from nothing but the Self (ewa) is this (world); ātmā abhūt sarvabhūtāni, the Self has become all these creatures and things.[8] He could have realised in the Purushottama, as the Gita makes abundantly clear and conclusive, or in the Purusha of the Veda and the Upanishads, the eternal oneness of Matter and Spirit, annaṁ Brahma, of the Self and the universe, of unity and multiplicity, vidyā and avidyā. That would have been, indeed, the true, the perfect Adwaita without the bewildering, inexplicable shadow of Maya hanging about it. But that was not to be. That was not the Will of the Divine and the Decree of the Time-Spirit. He had been commissioned to salvage the absolute reality of the Brahman out of the nebulous uncertainty and studied imprecision in which Buddhism had sunk it. He did a great service to Hinduism, and the greatness must not be impugned even if we find, as we certainly do in the light of the later developments of Hinduism, that his exclusive affirmation had to be supplemented and made all-embracing in order to reach the integral concept of the Purusha or the Purushottama. Each great soul comes to give to the world just what is needed at the moment, and nothing more. We shall treat of Shankara’s philosophy of Brahman and Maya elaborately in a subsequent chapter.

However, that was the experience Sri Aurobindo had when he sat with Lele for three days. He himself tells us that it was contrary to his own ideas, and, we can say, contrary to his natural inclinations too. For he was always, from the beginning, against life-negating or world-shunning Yoga. Later, as it is known to all, he travelled far beyond this initial, trenchant experience to the all-reconciling truth of the Supreme Person, Vāsudevaḥ sarvam, puruṣāt na paraṁ kiñcit. Writing again on the same experience, he says: “There was an entire silence of thought and feeling and all the ordinary movements of consciousness except the perception and recognition of things around without any accompanying concept or other reaction. The sense of ego disappeared and the movements of the ordinary life as well as speech and action were carried on by some habitual activity of Prakriti alone which was not felt as belonging to oneself. But the perception which remained saw all things as utterly unreal; this sense of unreality was overwhelming and universal. Only some undefinable Reality was perceived as true which was beyond space and time and unconnected with any cosmic activity, but yet was met wherever one turned. The condition remained unimpaired for several months and even when the sense of unreality disappeared and there was a return to participation in the world-consciousness, the inner peace and freedom which resulted from this realisation remained permanently behind all surface movements and the essence of the realisation was not lost. At the same time,” here Sri Aurobindo comments on his later and fuller experiences, “an experience intervened: something else other than himself (Sri Aurobindo) took up this dynamic activity and spoke and acted through him but without any personal thought or initiation. What this was remained unknown until Sri Aurobindo came to realise the dynamic side of the Brahman, the Ishwara, and felt himself moved by that in all his sadhana and action. These realisations and others which followed upon them, such as that of the Self in all and all in the Self and all as the Self, the Divine in all and all in the Divine, are the heights… to which we can always rise; for they presented to him no long or obstinate difficulty.”[9] But even this was not the end. There were other heights to scale, other victories to win. But we shall study these things when we come to study his spiritual life as a whole. We shall only quote here a short poem which he wrote much later on this initial experience of Nirvanic calm and silence:

NIRVANA

The mind from thought released, the heart from grief

Grow inexistent now beyond belief;

There is no I, no Nature, known-unknown.

The city [10], a shadow picture without tone,

Floats, quivers unreal; forms without relief

Flow, a cinema’s vacant shapes; like a reef

Foundering in shoreless gulfs the world is done.Only the illimitable Permanent

Is here. A Peace stupendous, featureless, still,

Replaces all, — what once was I, in It

A silent unnamed emptiness content

Either to fade in the Unknowable

Or thrill with the luminous seas of the Infinite.[11]

We have allowed ourselves this digression and this long excursion into spiritual matters in order to understand the precise nature of the first decisive experience which Sri Aurobindo had with Lele — an initial but very powerful experience which became the granite base of his subsequent much wider and integrative realisations.

[1] Vishnu Bhaskar Lele was a fire-brand nationalist in his youth, but his contacts with a few spiritual persons converted him to the life of a Yogi.

[2] Life of Sri Aurobindo, A.B. Purani.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Sri Aurobindo on Himself and on The Mother.

[5] Sri Aurobindo on Himself and on The Mother

[6] Italics are ours.

[7] Sri Aurobindo on Himself and on The Mother.

[8] Akṣarāt saṁbhavati viśvaṁ — The universe is born of the Akshara, the Immutable Absolute.

[9] On Yoga II, Tome II.

[10] He has the picture of the city of Bombay before him. We shall write about it in our next article.

[11] Collected Poems of Sri Aurobindo.